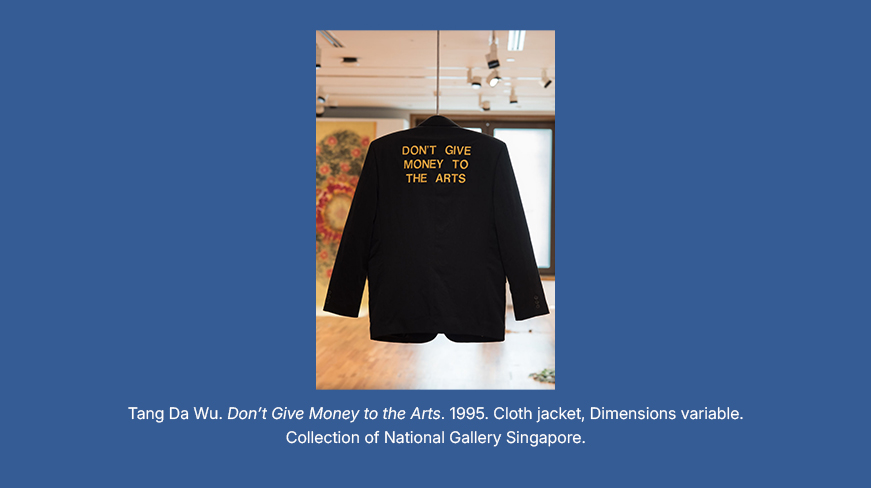

Materials: Cloth jacket

Don’t Give Money to the Arts was a performance that addressed pressing issues in the local arts scene at the time in a bold and activist manner.

Tang Da Wu approached then-President Ong Teng Cheong, asked him for permission to put on the jacket, then presented him with a letter, which read: “I am an artist. I am important.”

When asked about the intention behind his performance, the artist explained that he wanted to let the president know that “the wrong kind of art” – presumably the modernist, abstract art displayed in the festival – was being funded.

Located at: Currently not on display

Teo Eng Seng invented “paperdyesculp,” a malleable mixture of pulp, natural fibres, and other commonplace materials. In this work, he embellishes a second-hand birdcage with paper pieces resembling classical columns, mimicking the opulence of grand mansions in Singapore's wealthy neighbourhoods.

Despite the theme of captivity, paper birds within the cage frolic between themselves in the gilded cage, symbolising the contradictions of affluent lifestyles and the trade-off between material comfort and personal freedom.

Located at: Currently not on display

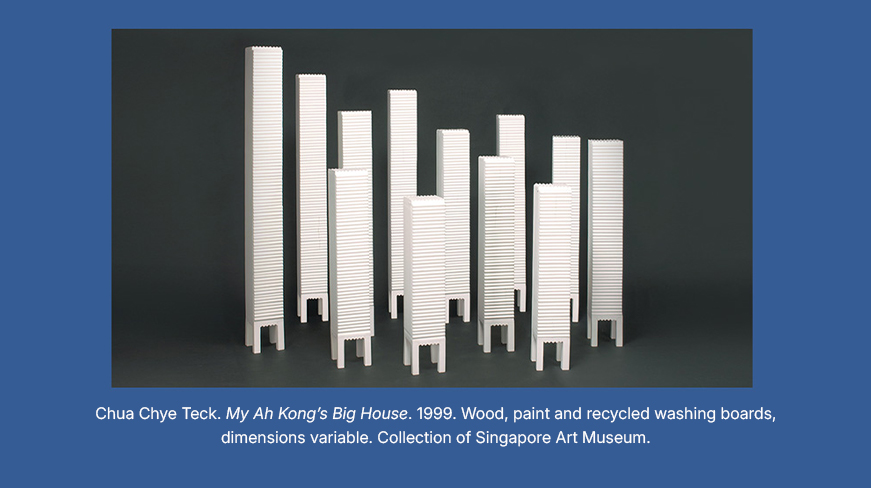

My Ah Kong’s Big House reflect on the development of the Singapore public housing, the impact that it has on the senior members of Singapore’s populace. The work derives the lived experiences of his grandfather who was uprooted from his village to these new developments. The recycled washboards come from Chua’s family factory.

Located at: DBS Singapore Gallery 3

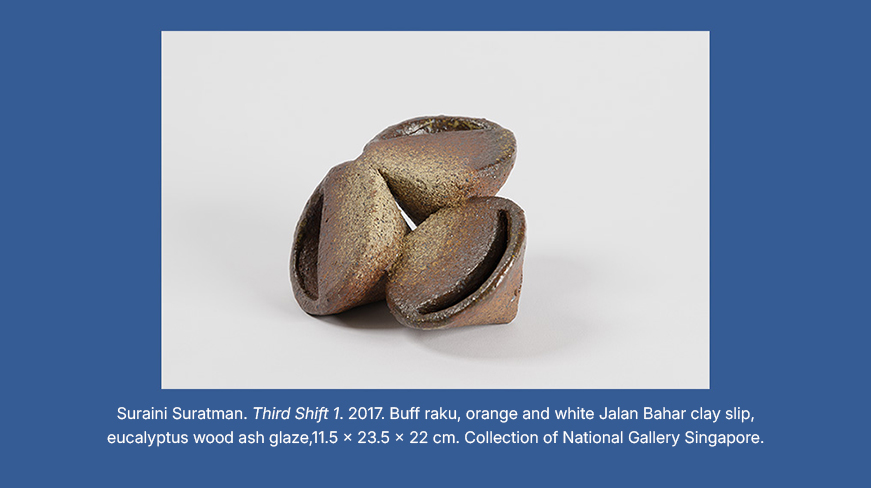

This work is a quiet yet potent mediation on the unseen labour of women.

Inspired by her mother, the work acknowledges the multiple roles women balance across work, family and community through three interconnected gasing (spinning tops). These forms, each relying on the others for stability, symbolise a delicate balance.

Expanding on sociologist Arlie Hochschild’s concept of the “second shift,” Suriani highlights the “third shift”: the often-overlooked contributions of women in volunteerism and social service.

Located at: DBS Singapore Gallery 2

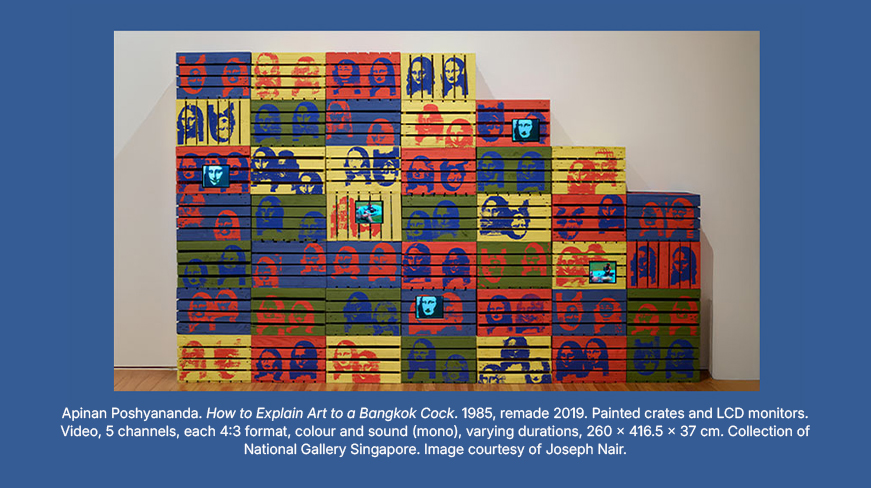

This multimedia installation incorporates video art and satire, challenging traditional art norms.

Distorted silkscreen prints of Mona Lisa is multiplied across beer crates, and in the video, turkeys, roosters, and chicks are shown learning about the famous painting, embodying the artist’s critique of the entrenched structures of Bangkok’s art world.

In the 2023 iteration of this work at the Gallery’s See Me, See You: Early Video Installation of Southeast Asia exhibition, chickens and chicks were included during the opening weekend amidst LCD screens showing digitised footage from the original video the artist had made.

For this presentation, the Gallery collaborated with Chicken Rescue Rehome, a group which advocates for the proper care of chickens in Singapore.

Located at: UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 12

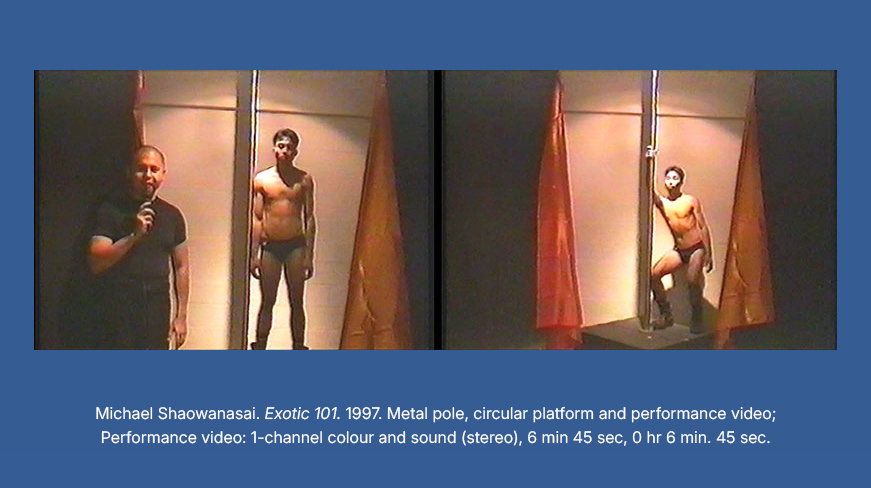

This satirical instructional video offering success as an exotic dancer is Michael Shaowanasai’s wry commentary on Thailand’s sex tourism during the 1990s.

The viewer is encouraged to follow the instructions provided in the video and dance on a fabricated A-Go-Go pole platform.

This invitation to participate in the work highlights the construction of the “exotic ideal” of Asia. In doing so, the work inverts the logic of spectatorship, forcing the viewer to grapple with the mechanics of seeing and voyeurism.

Located at: UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 14

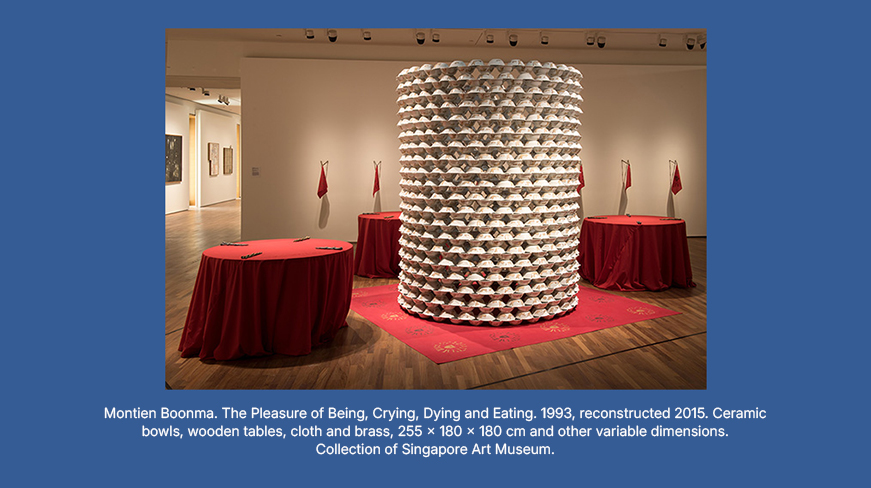

The work reflects Montien Boonma’s meditation on the Buddhist cycle of birth, death and rebirth, shaped by personal grief following the loss of his wife to cancer. In Buddhist practice, placing offerings in monks’ bowls is a way of gaining merit.

For Boonma, the bowl’s hollow became a contemplative space – one which offered refuge from worldly suffering and a site for inner healing and spiritual reflection.

Located at: UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 13

In this artwork, Mella Jaarsma used an entire goatskin as a reference to the Islamic ritual of sacrificing two goats for the birth of a male baby and only one goat for a female baby, challenging gender biases and the ritualistic role of animals as sacrifices.

The gaps between the seams on the costume installation remind us of the early clothing worn by primitive human civilisations, reinforcing a sense of primal origin.

Located at: UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 14

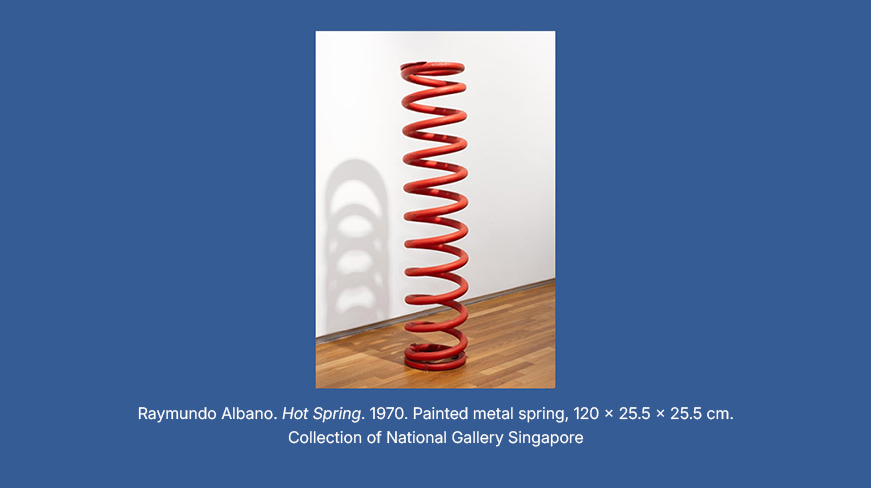

Hot Spring made use of an industrial object, commonplace in the post-World War II years of rebuilding the capital city of Philippines, Manila, which had suffered heavy wartime destruction.

Albano once expressed that “bringing pieces of junk to the gallery for aesthetic perception would lead one to consider virtues of things considered ugly and cheap.” He saw these artistic strategies as vital prompts to audiences to notice the rapid pace of developmental change around them.

Located at: UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 11

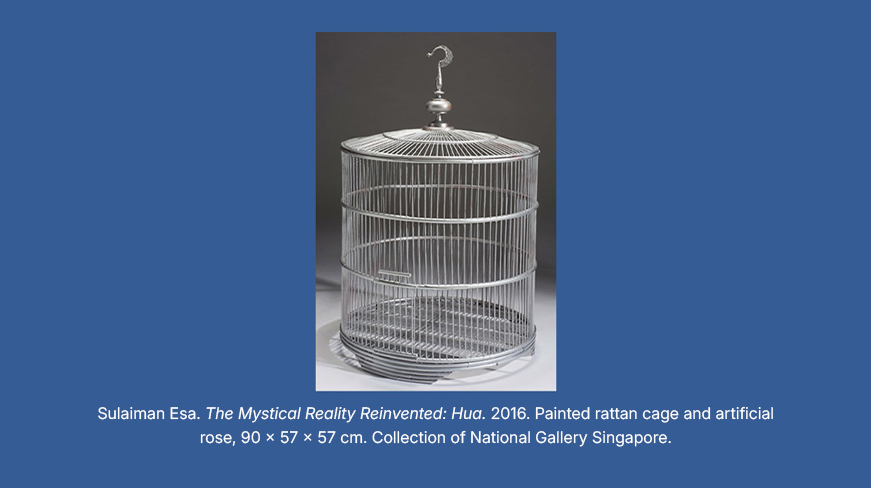

This work re-imagines the empty wooden bird cage used in the original Towards a Mystical Reality exhibition by Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa in 1974. In this remake by the surviving half of the duo, Esa recontextualises the empty bird cage from a Sufistic mystical viewpoint to represent the fragility of life.

Painted in silver, this shift in coloration also denotes a break from the original set of objects which included other quotidian materials like a chair, half-drunk Coca Cola bottles and a raincoat.

Presented alongside a published treatise, the 1974 exhibition aroused many debates within Malaysia’s art community around the relationship between art, space, and time.

Located at: UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 11