Ask a Curator | Minimalism: Space. Light. Object.

Throughout the exhibition Minimalism: Space. Light. Object., visitors posed their questions on the show through our social media and front-of-house staff. The shows’ curators respond to a few of your queries in this post.

Throughout the exhibition Minimalism: Space. Light. Object., visitors posed questions on the show through our social media and front-of-house staff. In this post, the shows’ curators—Eugene Tan, Russell Storer, Silke Schmickl, Goh Sze Ying and Eve Hoon—respond to a few of these queries on the recently concluded exhibition.

“Why did the pioneers of Minimal art choose black as the colour for their paintings?”

(Editor's note: This question refers to the first section in the exhibition on colour-field painting, which opens with a room of black paintings by Ad Reinhardt, Frank Stella, Mark Rothko, Tadaaki Kuywama and Barnett Newman.)

Actually artists at the time did not exclusively use black! The first section in the show, which focuses on monochrome, colour-field painting, also includes a blue painting by Tadaaki Kuwayama and a red painting by Yayoi Kusama in the next room. The choice to begin the exhibition with a room of only black paintings was a curatorial choice, to emphasise the radicality of these artists’ approaches to painting at that point in time. In choosing to focus on black, we were inspired by Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting (featured in this room) and his desire to produce a non-objective, pure, spaceless object, as well as Frank Stella’s series of Black Paintings (two are featured in this room) which are widely considered the first Minimalist art works. Both artists were highly influential on the development of Minimalism and an important starting point for us in developing the exhibition.

“Why can’t we touch the artworks? Weren’t many of the works originally made to be touched?”

This is a good question. You’re right that some of the works were initially made to be touched or even walked on (in the case of Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower seeds or Carl Andre’s Steel-copper-plain). In the past, visitors would also have been able to walk between Robert Morris’ four mirrored cubes, and become aware of the way their perspective of their bodies and the gallery space shifted. The reason the works are now unable to be touched is due to the conservation requirements from the lenders of the art works, who are responsible for the work’s safety and long-term preservation. This can be one of the challenges of staging a historical exhibition, in that the way we display works today can sometimes differ from how they were originally shown.

“My question is on Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #338, which spans an entire wall in the first gallery. Did the artist draw the work by hand, is it executed by someone else following his instructions?”

All of Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings are drawn by professional draughtspeople following his instructions. The one displayed in the Gallery was executed by an artist authorised by the Estate of Sol LeWitt, with the assistance of four local artists in Singapore. The title of the work contains the instructions for executing it, though they are also site-specific, as the scale of the drawing depends on the size of the wall on which it is displayed. LeWitt was one of the key figures not only of Minimalism but also Conceptual art, and he believed that the concept or idea, rather than the execution or physical object itself, constituted the artwork. This instructional approach also rejected the traditional importance placed on the artist’s own hand. A fun fact is that the first version of Wall Drawing #338 in 1971 was actually executed by Kazuko Miyamoto, another artist in the exhibition, whose work is displayed in Gallery A. She was LeWitt’s first studio assistant in New York.

“What spices are placed inside Montien Boonma’s installation Nature's Breath: Arokhayasala, and what is the importance of smell to the experience of this work?”

The work features a mixture of herbs and spices like citronella, pepper, jasmine and turmeric, many of which are used in Buddhist healing rituals. Buddhism was a strong influence in Boonma’s practice, as both he and his wife sought spiritual healing to overcome their illnesses. The scent recalls a temple, as the title of the work suggests, but also draws viewers into the space, inviting them engage with the work not only visually but also physically, sensually and spiritually.

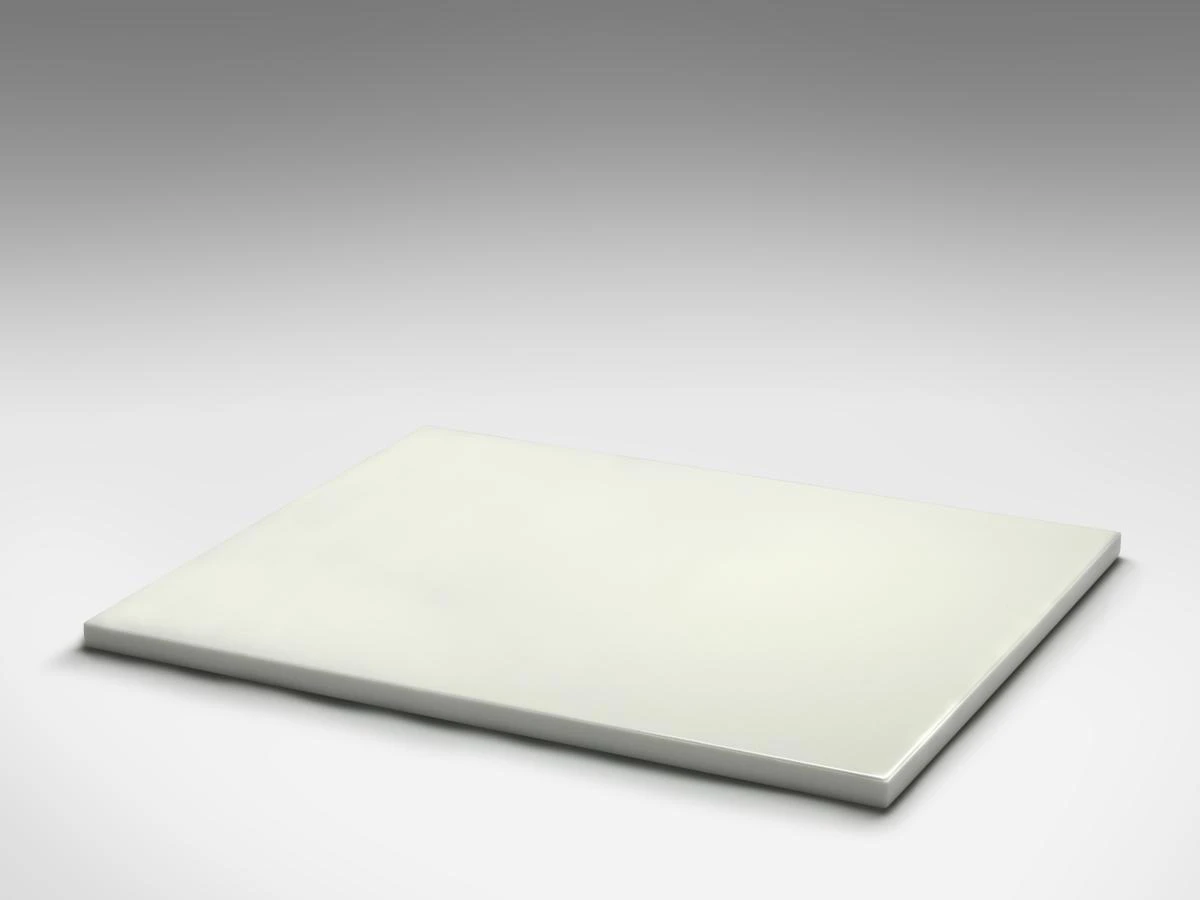

“How much milk is poured onto Wolfgang Laib's Milkstone every day?”

About 1 to 1.3 litres of milk is poured onto Wolfgang Laib’s Milkstone each day. The pouring of the exact amount of milk, so as not to have it spill over the edges, is characteristic of Laib’s labour-intensive and methodical approach in his works. They are often made with ephemeral and perishable materials like milk, or pollen, requiring a tremendous amount of physical and mental commitment to create.

“Are there plans for a maximalism exhibition in the near future?”

This exhibition actually already includes some Maximalist works! Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. is a two-venue exhibition, and the other venue, the ArtScience Museum, features a section that focuses on Chinese Maximalism. This is a term given by the Chinese art historian Gao Minglu to a tendency in Chinese contemporary abstract and minimal art, in which the process of making the work is based on spiritual and cultural practices that are part of the artist’s life and environment, and not just focused on the art object.

Editor's Note: Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. ran from 16 November 2018 to 14 April 2019 at the Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery at National Gallery Singapore.