Inside Gallery’s Kolektif: A 1-0-1 Intimate Art Affair

Kolektif is a group of 24 individuals brought together by a shared vision—to design and execute some dope digital programmes for the 2021 edition of Light to Night Festival. For three days in June 2020, these 24 Gen Zs and young millennials got together for their first meeting. Dana Rizal and Kuwabara Tsusha introduce the programme, dubbed Kolektif 101.

Image courtesy of Kolektif.

COLLECTIVE (read Kolektif)

/kəˈlɛktɪv/

adjective

done by people acting as a group.

noun

a cooperative enterprise.

The Initial Meeting

A rainy Saturday morning in June, 9.49 AM.

You’re at home, camped in front of your computer. Your cursor hovers over the button that says “Join Meeting.” You’re about to enter a room filled with 23 people you have never met in your life and it scares you, just a little bit. What if everyone else are like present-day Leonardo da Vincis or Georgette Chens?

9.50 AM, with sweaty palms and a racing heart, you join the meeting. Whatever it is, it’s too late to back out now.

Meeting the coordinators and the rest of the members feels surreal. No longer words and images on Instagram but real people, they introduce themselves in a series of three-minute PowerPoint presentations. You’re psyched to discover that Kolektif is filled with earnest young creatives, all connected by a mutual hunger to learn more about the arts and the museum space. You come to realise that although everyone in Kolektif is different, they are all equal. One after the other, these presentations start to feel like a cinematic reel of autobiographies.

Despite the good vibes all around, the introductions make you feel a little drained. But just as your energy wavers, you’re made to enter a break-out room for some creative exercises.

The Break-Out Rooms

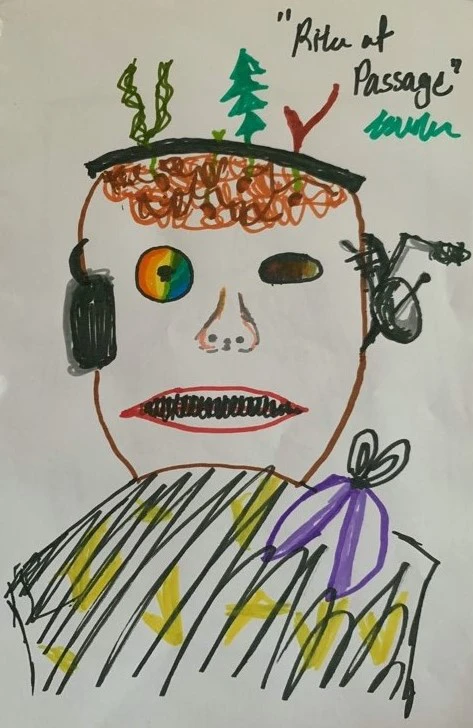

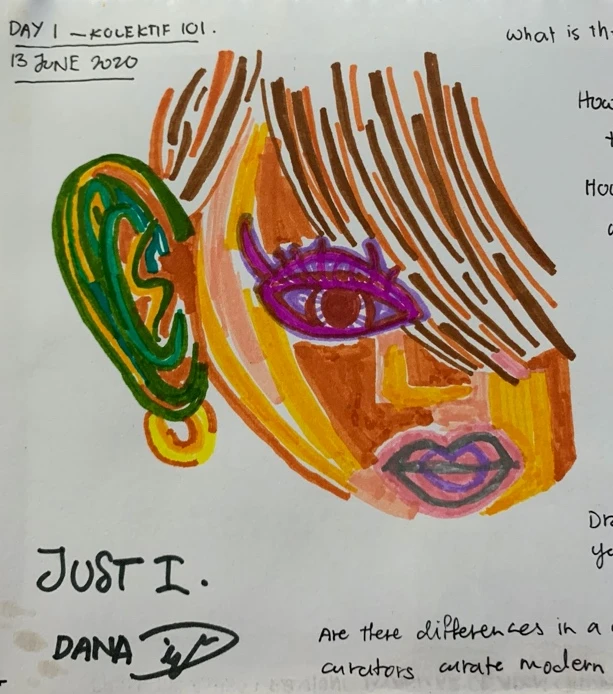

The four others in the room are silent. As music plays softly in the background, you dig deep to respond to the creative prompts, focusing only on yourself. In the first exercise, you’re made to confront your own image—and yourself—through a self-portrait.

You wouldn’t go so far as to say that you’re an artist. Not at all. This quiet time for self-reflection on your own participation in Kolektif allows you to think about what it means to contribute, and why. As you sit there contemplating what to draw, you wonder: “How can I contribute to the arts with no art-related experience?”

As counter-intuitive as it sounds, perhaps the lack of experience is a contribution in itself. The lack of experience brings about fresh perspectives and ideas and serves as a bridge between the museum and a general public that isn’t all that familiar with art in a museum setting.

In another activity, you work with your team to create and perform a short poem centered on identity and belonging. It is nerve-wracking to be vulnerable with people you barely know, but these exercises make you appreciate the uniqueness of your perspective.

I am from a hospital in Shanghai

I am from a small island in Japan

I am from a tiny red dot called Singapore

I am from the light drizzle in the middle of the night

I am a contradiction that proves to be a false dichotomy

I am from a place of subtle, unspoken yet intense love

I am from past mistakes and traumas

I am from somewhere else

Tsusha

I am the stories I’ve heard

The things I’ve read

The people I’ve met

I am my grandfather and his keris-sharpening

My ancestors who gave me this skin

Dana

Over time, you find it easier to connect with others during these break-out sessions. You talk to one member about meeting a stranger online during the circuit breaker period. You share mutual confusion over some heavy art history content with another. These are your first steps into a new, yet now strangely familiar, community—a budding community of youths among awe-inspiring artists, senpai festival programmers, and ultra-intelligent curators.

The Art History Lessons

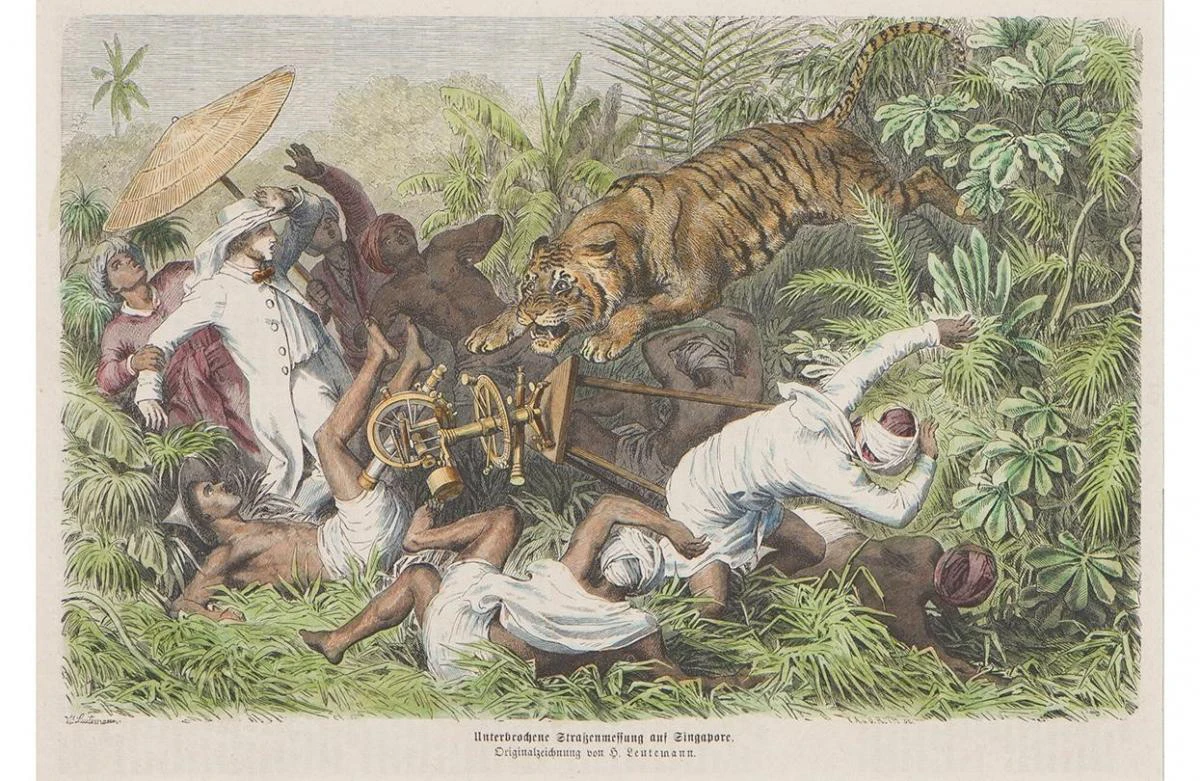

You never thought you would have the privilege of engaging with museum curators about their curatorial journey and the artworks they curate. Replete with historical tidbits and sometimes mind-blowing facts, their lessons bring the Gallery’s collection to life by adding a new dimension of understanding and appreciation for the works of art you’ve seen before. For example, you definitely didn’t know that fake news could take the form of a lithograph. Heinrich Leutemann’s print was based on a real-life encounter between the first Government Superintendent of Public Works in Singapore George Coleman, a group of Indian convict-labourers, and a tiger. Later known as the “George Coleman incident,” the print is likely an exaggeration of actual events.

You are introduced to the narratives of colonialism and de-colonialism in Southeast Asian art, and that power-struggles and notions of dissent permeated artmaking in the region. During these lessons, you are presented with gaps in the art history of Southeast Asia. Where are the women artists? The Malay artists? The queer artists? These lessons prompt you to think deeper about the narratives you have been taking at face value. As the curators present more material about each of the UOB Southeast Asia Galleries, you are heartened to know that these issues are not overlooked: the very gaps they identified are being addressed.

When it comes to the inevitable question-and-answer segment, you start to feel a bit insecure. You think: “What if my questions are stupid?” But you realise that no one is out to judge you, and that you have to seize this rare opportunity to explore the subject you are so passionate about with people who are experts in the field. As you learn more over the course of the day, you start to see certain trends, and some questions come to mind: “Why were brown bodies such a popular subject matter?”, “When making works of art, did artists react to specific phenomena?”, “What systems did they challenge?”. Not all our questions could be answered, but the art history lessons got us thinking about the way narratives about art have been shaped.

The Eye-Opener

What do a tech innovator, a writer, a partnerships manager and an art installer have in common? They are all incredibly essential to the Gallery! There is much more to a museum than the aesthetic artwork—think about how those artworks get into the Gallery in the first place. Art installers strike a balance between delicate touch and brute strength to wrangle works of art—the fragile, the oddly-shaped, the very-large—into the Gallery. You may or may not know that the Gallery is supported by generous art patrons and donors as well, and that there exists an entire department dedicated to managing and developing these important relationships. A lot of consideration goes into drawing people in—the museum experience is a collaborative effort by a diverse group of individuals. Your eyes are opened when you see that you don’t need an art degree to work in a museum, and you don’t just have to be a curator. The Gallery consists of people with such different backgrounds! And the realisation finally hits you: Kolektif is a microcosm of this colourful ecosystem at work.

Complicating the narrative

"A progressive art museum that fosters and inspires a thoughtful, creative and inclusive society."

National Gallery Singapore’s vision statement

Thinking back on the programme, you vaguely recall something a curator said, about how it was important to "complicate the narrative". For example, images of idyllic landscapes from the past no longer hold water in our modern times, where climate change is an urgent concern. Our landscapes no longer look like this, and if they do now, they’re certainly under real, existential threat. Perhaps Kolektif complicates the existing narrative of how art should be presented and understood by reconciling traditional notions of art with the ideals held by the younger generations. While the Gallery itself retains historical weight in its physical presence, we can be the platform to bridge established narratives with contemporary concerns. And just maybe, the Gallery of the future can be an active participant in society to make art accessible and equitable for anyone—even if it isn’t necessarily everyone’s cup of teh.

By the end of Kolektif 101, you’re feeling inspired by all the individuals you’ve met, and a renewed sense of purpose and belonging. In all honesty, you still have mixed feelings for what’s to come in the next few months—feelings of apprehension? Excitement? But something has changed, and you feel less anxious knowing that all 24 of you are in this together.

A rainy Saturday evening in June, 5.49 PM.

For the last time, you move your cursor to the little red button that says “End”.