Out of Isolation

Plant Interrupted: Histories through a Botanical Lens

This new season of Out of isolation invites writers, poets and members of the art ecology to reflect on our current context through perennial issues such as gender, ecology and climate change. In the first post of this series, Dương Mạnh Hùng shares how the first botanical compendium of Vietnam, which they found on an internet archive, encouraged them to reimagine the stories of botanical art in Southeast Asia through the female-queer gaze.

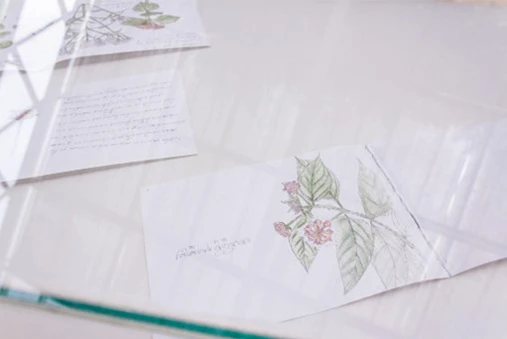

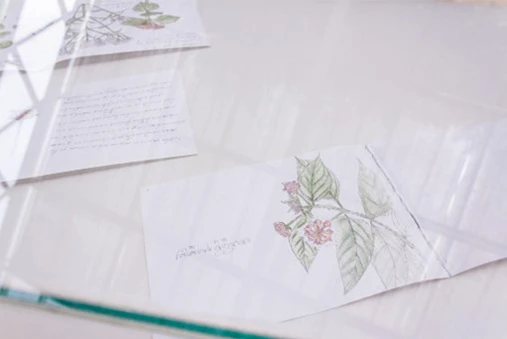

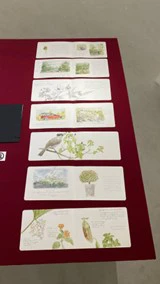

Babad Tembeleka

Pen and watercolour on sketchbook, 14.8 x 21 cm

Image courtesy of Jakarta Biennale 2021 ESOK

As COVID-19 becomes normalised within our lives and we gradually emerge from physical isolation, our experiences of being, making and relating to one another have shifted indelibly. This new season of Out of Isolation invites artists, writers, poets and members of the art ecology to reflect on our current context through perennial issues such as gender, ecology and climate change—themes that ground their research of modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art. We hope that this series of responses will trace and reflect this moment as we learn new strategies on how to be together again, through and with the many forms of art and its practices.

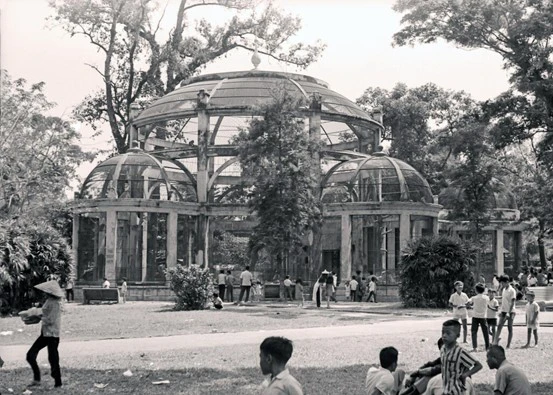

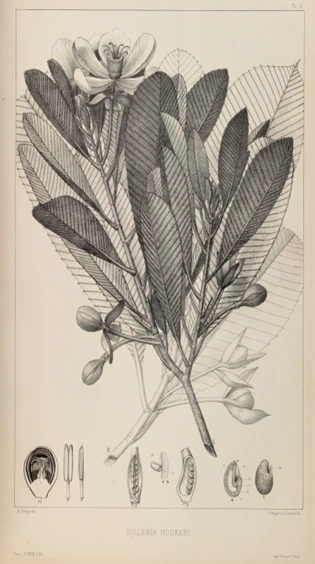

In 1865, Jean Baptiste Louis Pierre (1833‒1905) arrived at the port city of Saigon, the heart of Cochinchina1—France’s first colonial conquest in Southeast Asia. Previously stationed at botanical gardens in Calcutta, he was invited by the French colonial government in Saigon to establish the city’s Zoo and Botanical Gardens,2 a research-focused institution specialised in cultivating, displaying and propagating various botanical species that served the purpose of urban planning in the new colony. Pierre was tasked with developing the herbarium in the garden, as well as introducing various species from other parts of the world, most of which have since been “naturalised” in Vietnam. One of Pierre’s most widely-known achievements is his magnum opus Flore forestière de la Cochinchine (1880‒1907). Hailed as the first botanical compendium of Vietnam, this series of ink-on-paper drawings is a record the trees planted at the Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens, annotated with Pierre’s own scientific descriptions and personal observations of each species and genus.

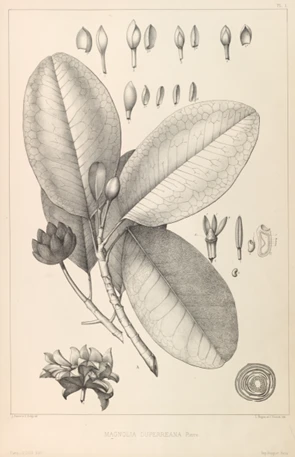

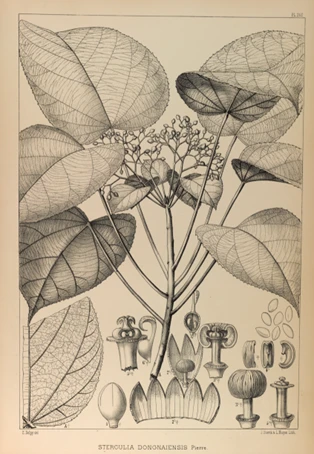

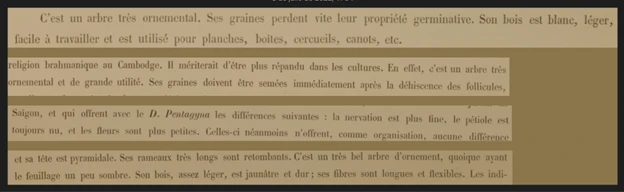

When I first stumbled upon this series, now stored in an open-source internet archive,4 I was mesmerised by the level of intricate details shown in each drawing. How each plant is disembodied into separate organs: branch, leaf, flower, bud, petal, stamen, pistil, etc.; how each of these organs had been magnified to an unimaginable scale, transforming a leaf into an elongated labyrinth of lines and shadows, a flower into an unfurling fountain, a fruit into an inflated womb of seeds ripe and ready for further dissection. I could feel the somewhat detached gaze of Pierre spiralling into each cell of the specimens, attempting to analyse their biological constitution in order to decipher their concealed utilities. His scientific descriptions also serve to illustrate this utilitarian gaze: length of leaf, hardness of wood, numbers of petals, shape of seeds. All neatly counted, measured, recorded, and categorised. No room for estimated or frivolous indulgence, only scientifically accurate calculation.

As Pierre became more intimate with these specimens through the act of drawing them, and the newly-founded colony by extension, his gaze ironically became more desensitised, unleashing a scrutinising intimacy that relishes in the obviousness of things; an embodiment of Hegelian savoir absolu—knowledge that is undistorted, objective, all-encompassing, and free from internal inconsistencies. His drawings are thus enmeshed in a violence that only comes from intimate knowledge, that revels in deconstruction and decontextualization, that exalts the scientific will to empiricism and repeatability: presumed detachment and objectivity. This is how Pierre, a white European man, must have perceived the colony, I thought, through its native trees: a body to be dissected, an uncharted territory that is deemed worthy of excavating and exploiting, a sacrificial lamb in the names of Science and Enlightenment.

| |

This violent intimacy is further ingrained as I read Pierre’s personal observations. Peppered across his annotations are terms such as “ornamental,” “of great utility,” “fine,” “petite,” “susceptible,” “sensitive,” “delicate”—words that echo the notion of the colony as always effeminate and subdued. Here, Pierre’s seemingly scientific gaze adds another layer unto itself: that of a patriarchal view through which Saigon’s ecological forms, expressions and substances are delineated; a male gaze that sets the precursor for imperial conquests. This gaze, already perpetuated through colonial painting, literature, photography and cartography, reduces Saigon to a docile and demure effigy that is readily categorised, collected, and conquered.

Nonetheless, I do not deny the fact that I myself am drawn to Pierre’s drawings—more by their visually striking depictions of native flora than by their imperialist undertones. The vividly detailed ink drawings bear affinity to realist paintings, where painters attempt to depict their subjects as truthfully and un-artificially as possible. Due to the fact that paint and colour must have been rare commodities in the early days of the colony, Pierre only used ink and pen to engender his drawings’ visual qualities. However, it is this exacting contrast between black and white, soft lines and dark shades, that further enshroud the drawings in a realist objectivity; it was as if by stripping the flora of their vibrant colour, Pierre has baptised them in the name of Botany, nipping them from their ecological context to place them into a sterilised canvas, where they are given a new purpose. Furthermore, by manipulating scale to transform each stamen and petal into enlarged ”texts” imbued with symbols and traces, under the guise of aiding botanists to gain empirical knowledge, Pierre has transformed the native trees into botanical Frankensteins: dismembered organs that float inside test tubes—strangers in their own home. This moment of deterritorialisation perpetually colours the experience of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s “subaltern,” where rootedness and rootlessness exist as two sides of the same coin.

Pierre’s pseudo-intimate and hyper-expositive botanical drawings and annotations can thus be read as a series of subconsciously and intertextually violent acts committed against the native flora of Cochinchina, reducing its ecology to a site for scientific conquest and extraction. It is no surprise that the industrial crops later introduced to, germinated in, and disseminated through the Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens became the seeds for the plantation system across the colony’s highlands. Here, botanical painting, as with other colonial scientific projects such as cartography or medicine, was deployed as a vehicle to impose and export a materialistic fantasy of the fertile colony. The history of botany—and botanical art—in Vietnam and Southeast Asia will always find its origin haunted by the shadow of the colonial impulse, a foreign seed that has lodged itself into the socio-historical soil of the region.

As Southeast Asian nations began gaining independence, we entered the modernist occupation with hesitant devotion to innovation, industrialisation, rapidness, and anxieties. To our misfortunes, we have carried the colonial remnants into our thinking, particularly in our relationship with plants—we see them purely as resources, either industrial or medicinal. The colonial project has successfully ruptured our ties to nature, rendering us as detached from our ecological milieu. This sense of “up-rootedness” sets the ground for multiple nation-building projects that blindly propel us into an unknown future at the expense of Nature.

And now, here we are, at the postmodern, where all innovations seem to have run their course; where industrialisation has reduced our environment to belligerent landscapes saturated by materialistic obsessions; where anxieties are internalised and magnified to an ecological scale. We are at a point where we cannot look at anything as definite and solitary, but rather as a net of interconnected and intertextual makeshifts. The presumed certainty of Modernism has exited the stage; salvation can now only be found in interstices, in-between ideologies, outside of the dominant male-colonial gaze that so colours our worldview.

This was my modus operandi during the botanical painting exhibition with curator Grace Samboh, a dear friend and colleague, for the 2021 Jakarta Biennale, titled ESOK. The project stemmed from my long-term interests in Lantana camara, a plant previously native to Central America that has now become “naturalised” to the point of being branded “invasive” in other parts of the world, including Southeast Asia.

A common weed seen as frequently in urban capitals as in rural villages, the Lantana has completely taken root in foreign soils. This is due particularly to its repertoire of characteristics that enable its survival in a variety of landscapes. Its leaves and stems are coated in a sap that renders it fire-resistant; its roots release toxins into the soil that stun the growth of neighbouring trees; its poisonous seeds are transported by birds for miles and miles; and finally, its preference for nutrient-depleted soil, which has become more widespread as deforestation becomes more rampant, allows Lantana to survive in the worst of environments, flourishing where few plants can grow. Yet, this widely popular plant remains in the shadows, so blended into the background that people barely recognise it. Lantana’s resilience thus lends itself to the narratives of the subaltern, the marginalised, the female, the queer and the precarity of a post-modern future, where survival skills become a mode of navigating such an unpredictable future.

As Grace, myself, and the ESOK curatorial team collectively researched Lantana camara, and how we can spin an exhibition out of its stems, we were constantly reminded of how the regional history of botanical art has always been seen through a male-colonial gaze. From botanical gardens to collections of botanical drawings, the tales of plants have been told from the perspectives of people—who echo how colonisers would have viewed their colonies—that do not represent our collective team of females and queers. Such a gaze, which is dead set on utility and extraction, would never have noticed the Lantana (indeed, the earliest written record of the Lantana in Vietnam colonial inventory is in 1953, almost a century after Cochinchina became a French territory). I was personally reminded of how my perspective, as someone standing between margins, has never made it into “official” historical accounts, just like how the Lantana is sidelined by specialists and citizens alike. Such a queer plant, always in existence yet blurred out of existence at the same time, is constantly subject to sous rature—under erasure, to borrow Derrida’s term. I find in this invasive “alien” a sense of camaraderie that links those seen as unwelcome, unwanted, and unfit. This only intensifies my conviction in its sublime power of representation, exemplified by the way it inserts its “narrative” so freely in any context, bending the textual reading of ecologies.

My desire to subvert this predominant male-colonial gaze came in full swing.

When we decided to invite the women artists of Indonesia Society of Botanical Art (IDSBA) on board for ESOK, our show serendipitously became one curated by women and queers, looking at the ecological and socio-political state of Vietnam and Indonesia through the female gaze. Accompanying the colored botanical paintings of Lantana camara by IDSBA members, Grace and I each contributed our own writings: while Grace wrote about exhibition making as a collective yearning among friends, I penned a short story where Lantana is embodied as female, with human-plant hybrid daughter: a dystopian future where “men'' have been corrupted; masculinity subverted; and the Earth’s survival depends on females.

In our show, ecology is no longer something to be perceived in a detached manner; it becomes viscous, immersive and overwhelming—a reflection of the postmodern impulse to search for limits at the tipping point, for connections where fringes meet and where demarcating lines brush against one another. In the end, that is how we as humans need to see our interlinking relationship with ecology: not as the beekeeper, but as the bee. We are also pollinators in the grand scheme of nature, and a more durational relationship with ecology, instead of an instantaneous one, will be our future mode of being.

The Lantana camara project has offered us an opportunity to reimagine the stories of botanical art in Southeast Asia as seen through the female-queer gaze, where we reclaim a violent vehicle previously utilised for scientific taxonomy and rebirth it as the pen and brush with which we write and paint ourselves into histories. The postmodern is feminine: we can no longer afford to view nature and ecology through superior and extractive lenses; instead, our impulse should now be directed towards cultivating the seeds of humility and co-existence, as if we have ever “existed” outside of nature. And as our pièce de résistance, we indigenise Lantana camara in our exhibition title, cleansing it of its Latin name, returning it to saliara and trâm ổi, names that roll sweetly off our tongue. To name something is to birth it into existence; to unname and rename it is to perform catharsis. Out of the shadow of colonial remnants, comes our final huzzah against the crumbling male-colonial gaze:

"Pengembara Molek / Cỏ Cắc Cớ / ꦏꦼꦝꦪꦺꦴꦃꦲꦤ꧀ꦠꦩꦸꦮꦒꦸ"

For a world that now pivots on precarity and uncertainty, moments like this bring much needed joy weaved out of solidarity and filled to the brim with hopefulness. Let us all cheer to that, temporarily, as we dream ourselves into a more harmonious and congruent existence, where we see ourselves as intricate patterns woven into sweetgrass braidings of nature, where our existence is complete and full by itself, and not merely serving as a reflective surface for yet another dominant narrative.

Notes

- Cochinchine, or Đàng Trong, is a historical exonym commonly used to refer to the region in Vietnam south of the Gianh River, including Saigon / Ho Chi Minh City, during the French colonial period (1887‒1954).

- Vietnamese name: Thảo Cầm Viên. They were commissioned to be built on 23 March 1864, by Admiral Pierre-Paul de La Grandière, commander of French forces in Cochinchina.

- This photo, along with other photos by Carl Nielsen is available at the Saigoneer: https://saigoneer.com/saigon-heritage/14719-photos-27-snapshots-of-saigon-in-1970-by-carl-nielsen

- The series is available here: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/125684#page/1/mode/1up

- In postcolonial studies, the term “subaltern” designates the colonial populations who are socially, politically, and geographically excluded from the hierarchy of power of an imperial colony, and the metropolitan homeland of an empire. Antonio Gramsci coined the term to identify the cultural hegemony that excludes and displaces specific people and social groups from the socio-economic institutions of society, in order to deny their agency and voices in colonial politics.