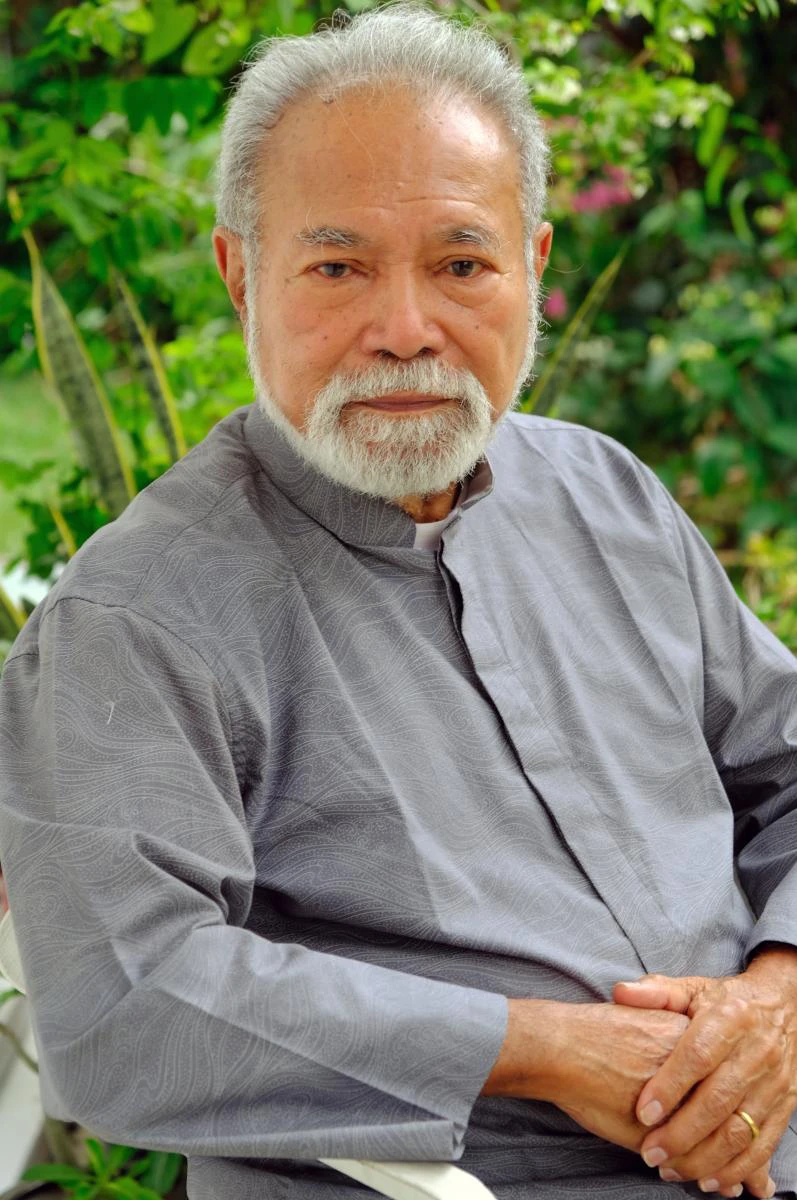

Painting and Poetry into Installation | In conversation with Professor Edwin Thumboo

On 25 May 2019, Professor Edwin Thumboo explored the rich relationship between art and poetry in a roundtable with National Gallery Singapore staff Elaine Ee (Deputy Director, Content Publishing) and Daryl Yam (Assistant Manager, Programmes). Although the conversation ranged from Singapore’s history to the purpose of art, much discussion centred around two poems in this volume, “Ayatana” and “Dancing Mutants,” which were analysed at length. Extracts of their conversation are presented here.

Detail of The Pleasure of Being, Crying, Dying and Eating,

1993, reconstructed 2015.

Ceramic bowls, wooden tables, cloth and brass.

255.0 x 180.0 x 180.0 cm.

Collection of Singapore Art Museum.

Ayatana

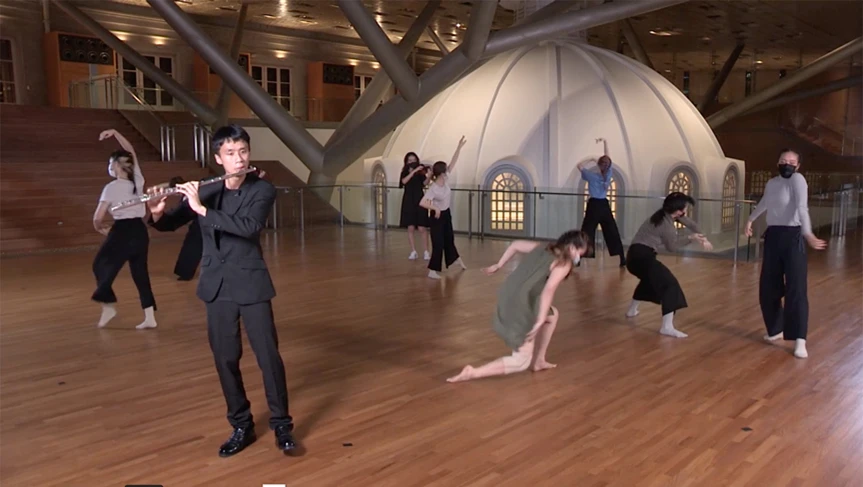

Elaine Ee: Perhaps I will start by talking a little bit about this work, for those of you who are not familiar with it. The Pleasure of Being, Crying, Dying and Eating was made by a Thai artist Montien Boonma, and looks at the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. The work also came out of his experience of death—he lost his wife to cancer prior to making this work.

Here, he explores the use of materials that are not normally used in art, so he employed materials like bowls, bones and napkins, looking at incorporating these more everyday objects into his works of art. And looking at what is unconventional comes into play in the work as well as in the poem.

I was drawn to the phrase “signifiers and signified.” That brought me back to my first-year university undergraduate literary theory course! So, a signifier can be a word, and the signified is whatever that word is describing. The signifier and the signified come together to form a sign, and the sign can only work if it is accepted by the person receiving it. That’s how it has meaning. The signifiers and the things that they signify in both the artwork and the poem get very subverted, very challenged. Instead of regular chopsticks being used as chopsticks, we see bones. And on the side of bowls, we don’t see a pretty pattern, we see a jawbone. These things make us stop and think; they add new layers of meaning into otherwise everyday objects, and challenge your conventional ideas of what these objects are. So that was one thing that struck me. Daryl?

Daryl Yam: I think in many ways the poem is a verbal account of how one might encounter the Boonma installation, which the Professor then uses as a way to illustrate the passage of life as understood by the human mind. Primarily because the whole poem is titled “Ayatana,” which refers to the senses with which we perceive the outside world. And here I think he does privilege, out of the six senses, the sixth—which is the mind and how it perceives mental objects.

I think it’s important then, to go back to the artwork which Professor Thumboo drew inspiration from. I’d like to mention a few things.

There’s this essay written by Sutee and Luckana Kunavichayanont, where they described Boonma’s installation as being “composed of dining bowls stacked up high in a circular wall; the outer surfaces of each bowl is printed with images of human finger bones, jaws and teeth. These features are apparently used to refer to the problem of our consumption for survival, the fragility of life, decadence and death. The state of man as subject of consumption by death.”[1] The essay then goes on to quote Boonma himself in an interview, saying: “The bowl series was developed from a saying by Buddha that I wrote in the back of a catalogue. The nature of a clay bowl, like that of an animal’s life, is impermanent. The pot or bowl is like the human body. I think of the clay bowl as a metaphor for the human body. The bowl that symbolises the eating habits of humans.”[2]

Now I mention this because I feel like the most striking and immediate images created by the installation involve familiar motifs commonly associated with eating; the eye immediately picks out objects such as bowls, circular tables, tablecloths and chopsticks, which the Professor too has noted. I half expected a lazy Susan to appear out of nowhere, but that’s missing. The installation borrows elements typical of a restaurant and then rearranges it to become something thoroughly unfamiliar. But there is an additional layer to the installation, as mentioned by Elaine. The real devil lies in the details.

Elaine to Professor Edwin Thumboo: In the last part of the poem, you almost switch gears and go from talking about the work to talking about Singapore: “We share bone, sinew and flesh, we SG Melayu,/China, Kling, Serani.” I really liked how you introduced the Singapore context.

Professor Thumboo: You see, all Singaporeans have got two identities. You have the national one, a Singaporean identity which I hope will grow, and then you have your ethnic one. Your ethnic one is much more complicated.

For me, this poem and the first stanza deals with the notion of our sixth sense, which is the most important of all the senses. In Asia, the sixth sense controls the other senses. This is not so in the West, where it’s got a series of other hierarchies that control the individual. You have your soul, you have your spirit—they are the ones that matter. And they are Christian concepts by and large.

Now the heron, the rose, the auguries, the self and the world: these are put there deliberately to suggest the importance of what the First World was, what the world is like. The heron of course is important in Egypt, and is also important for the Welsh and the Chinese. Then the auguries: you think of William Blake and the “Auguries of Innocence.” And if you look at the self and the world, they have always been important in every culture! The self, the individual and the world. Which is more important: the world or the self? It’s the self really, not the world. The world—you use it. You know it’s there, you know you’ve got to meet it, and if you live in Singapore the world is pretty complicated.

The next stanza has to do with the individual still. And what do we have here? The ten listed religions in Singapore. We are one of the few nations in the world that has no state religion, instead we have this Inter-Religious Organisation. I have looked into how religions grew up in Singapore: On one side of the Singapore River are the religions from Europe, such as Christianity and Judaism, and all the Asian religions are on the other side, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Taoism. This kind of division was accepted because the Europeans used to be situated on one side of the River while the Asians were on the other side. So here in the second stanza you have the individual behaving as he does when it comes to his religion. This is why I have that little line: “Basic. Universal.” Those two words divide the general statements in the first two stanzas from Montien’s very special one.

Now what happens here is that Montien wanted to change the direction of what he saw as the main energies of art in Thailand; change it in a very fundamental way. What he does in this installation is to use the concept of celebration, which is so much a part of life throughout Southeast Asia. And yet celebration—because of its discipline, its traditions, its limits—has got its restrictions; you don’t overdo it. What he does though, is to say that the same things that keep us alive and healthy, can become destructive when pushed into their limits and let free.

So if you look at his installation, what do you have there? The tower built from bowls. And if you look at the bowls, the bowls have got symbols: The lower jaw. The body denuded in its most basic structure. The mouth, the part that feeds you. The hands. So much so that the tower is built solidly from these bowls, and yet the bowls themselves are compromised by the lower jaw. And if you look at it very carefully, you find a stretch of intestines at the very top of the tower of bowls. He extends that into the feast.

And what’s interesting is the chopsticks are our couples and our meta-couples! Can you imagine our chopsticks there, they are our bones. You cannot find a greater contrast. That makes an ultimate contrast between Man with his flesh and muscle, and Man left bare and denuded. So, on the one hand you have the celebration, and on the other you have Man in his most primitive, bare form. For me, it was a real revelation. I went back to the installation about five times; every time I saw something new, something new, something new.

I stopped visiting museums when I was about 30, I only went occasionally for something special. But this time I came back. And this museum has been a tremendous experience for me because I’ve come back to it, I’ve become a student again. I’ve started learning.

Dancing Mutants

Professor Thumboo: Now this is a big painting, and the painter wanted to revive the basic colours that define his country for him. And of course, green is the most powerful. Look at the colours! For me, Dancing Mutants is important because, firstly, Ocampo I think is reinventing a surreal Filipino. The true Filipino, the Filipino that comes from the very earth itself in the colours that are best for the Philippines—the volcanic red that gradually cools off and turns into green.

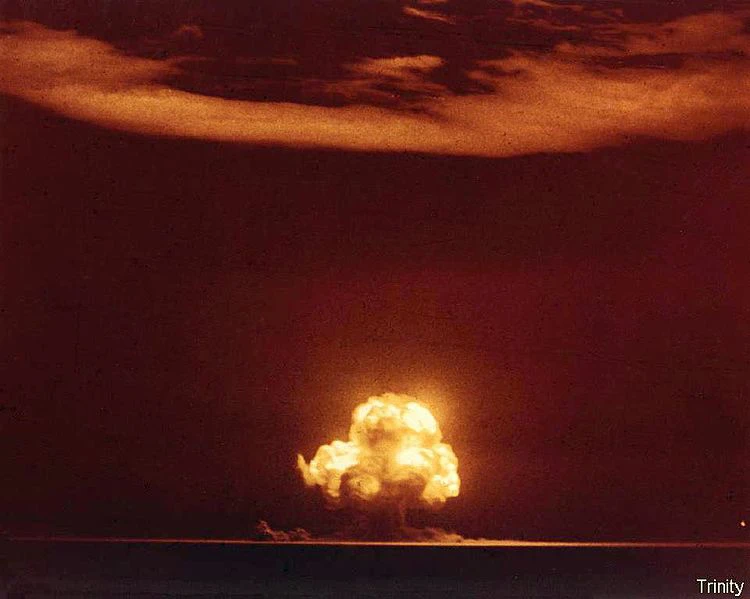

So: “Brighter than a thousand suns, I am become/Death.” You see what happens is that Ocampo remembered the testing of the first atomic bomb, and “Brighter than a thousand suns, I am become Death” is what went through Robert Oppenheimer’s mind when he saw the tremendous explosion. And you also have to remember Shiva, the Hindu god who is Death but also the creator.

Ocampo wanted to give his work a basic history, so he thought of the atomic bomb. Whether you like it or not, the history of the creation of your land itself becomes your prime history. And I just wonder: when Man left Africa through the old wide gorge and so on, how did he carry the memory of his tribe, of his old home in Africa with him? I don’t think he took very much, really.

Now the last line “May your tribe increase” comes from a poem by Leigh Hunt. So Dancing Mutants, really, is dancing with a real man. This is the new Filipino.

Elaine: On that note, I’d like to share something about this artist. Ocampo was part of a group of Filipino artists who, like Montien, were breaking away from what they saw as convention. Ocampo’s group called themselves the New Realists and they were moving away from art in the Philippines that was very representational, and could perhaps over-romanticise the Philippines through landscapes that portrayed a very idyllic view of the country. His use of abstraction was his way of distancing himself from that.

In the painting you see very clear reds and greens with darker areas in between, and Ocampo says: “There isn’t a single square inch in my painting where you can find a pure hue.”[3] So if you look at the red, you may think it is red. But if you look closely you will see that its actually a mix of shades, and I think the Professor has elaborated on and alluded to this—the mix of beauty, destruction, pain, reconciliation of death, and then rebirth and regrowth. You can “re-new” and “un-crust.”

Daryl: And I personally see a lot of the Ocampo painting in the Professor’s poem. But while you personally saw human beings, I saw a lot of plants. Specifically, I was actually reminded of wild holly, clusters of red berries and branches of serrated bright green leaves. And I think it’s precisely how these shapes intertwine and grow in the Ocampo painting that bears repeated mention within the poem as well. As you can see, he uses words like “re-configure,” “re-blooms,” “charged and changed,” “outstretched arms and legs,” “splices,” “conjugates ,” “shape,” “shade,” “counter.”

If we want to think about mutants, we have to think about how mutation also works within the poem. And I think there’s also a lot of intertextuality because the Professor has very clearly referenced the Bhagavad Gita and also Robert Oppenheimer, who recontextualised the poem, before going all the way back to Leigh Hunt at the very end. What’s interesting is that the Professor has a really wonderful grasp of history; the poem reaches back into multiple different times, and the mutations also manifest in the way it recontextualises different contexts.

Because of the way the poem ends, it can be read as a letter to the painter. But instead of “To H.R. Ocampo,” you actually titled your poem “H.R. Ocampo, 1965,” as though the poem itself was almost an extension of the painting. And I have to ask, because you are Professor Edwin Thumboo and so much of your work blends the personal and the political, when you add the word “1965” and you mention things like our island’s birth, and you talk about Man and our primary history starting from the independence of our nation—how do you see your idea of Singapore captured in this painting?

With this poem and the last, you talk a lot about our histories, and how messy the political systems are here and in the West. And I just wanted to know: is transcendence something you seek? Or the reverse?

Professor Thumboo: Yes. The problem is that we have developed so fast. Those of us who are old had to go through all the phases. You know, I was Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at National University Singapore for eleven years, and eleven years is a very long time, I can tell you. There was so much that was going on! We knew that what we were doing, what we were putting in place, would only be there for this period of time. That it would have to yield, it would have to go, but in the meantime, it was the best we had. We were constantly changing. We were constantly changing, all the time.

Daryl: So we are the dancing mutants?

Professor Thumboo: We are the dancing mutants, yes! And the problem is this: the older you are, the more mutants you have.

Art and Poetry

Audience Member 1: What struck me with this Ocampo piece in particular was change, and one aspect of change is that it’s never done. Maybe one thing you could share with us is what you think is coming next. In terms of where this painting is going? What is the mutation?

Professor Thumboo: You see, for me, what is important about the painting is that it is what it is and it will always stay that way for me! For me it will stay that way. And this is what happens to all of us. We go to a painting, we make sense out of it—that’s how we possess it and it becomes part of us.

When I first saw Picasso’s Guernica, the tremendous piece of work, my immediate reaction was: so what? And then I looked at it very carefully. And then it made sense to me. And I carry it with me, all the time. It’s there—I’m not aware of it, but there are moments where I become aware of it. One of the things that has benefitted a person like Ocampo is for him to have brought together all these things leading to the painting. If you look at it, you wouldn’t think of Robert Oppenheimer. But once he says Robert Oppenheimer was there, then you can see the significance of the thing! How it enters, how it feeds, how it becomes part of the narrative.

But a person may have as much instruction from the painting without even knowing Oppenheimer. And this is why art, great art speaks differently all the time to different people. I’m afraid to look at the old paintings that I liked, because they don’t mean the same thing now. This is part of the greatness of art—that it moves. It changes and it fits you. And it still speaks to you, it’s still relevant.

Audience Member 2: You said that art becomes a part of us, so I’d just like to ask: do you think art necessarily has the purpose of changing our perspective, or can your response—so what?—be a legitimate response to art?

Professor Thumboo: There are different paintings. There are a few paintings that speak to me and silence me. Guernica isn’t one of those. I sometimes like it, and sometimes wish there was something else there. It doesn’t speak for me completely but it is an important painting, partly because it has an importance within the context it exists now.

I have to see why it is important. I might not share it, I might not say it is important to me in the same way. If you tell me I’ve got to keep ten paintings, would it be one of them? The answer is no. But I can see why it’s important for some people who lived through the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s before Francisco Franco won everything. Now for them, a painting like Guernica might be the painting, because they were there and are part of the experience of which Guernica is one of the major statements. For me, what ultimately matters in my own life, however modest and limited it is.

I think in the end you have to believe in what you like, and you must have reasons for what you like. We all have our own favourite paintings. And in fact, the cover of my book of poems A Gathering of Themes is something done by my grandson when he was eight years old. I‘ve enlarged it for the book and for me, it’s an important thing because I like the colours there, I like the long, terrible tail he gave it, and I kept everything. They wanted to cut the tail, but I said no! Don’t cut the tail. You let it get to the edge of the book.

In the end we make our own art. We make our own art, because that is the art we keep.

Editor's Note

Professor Edwin Thumboo's Ayatana is part of the Gallery's Words on Art series -- books dedicated to articulating the intersections between visual and literary art. Ayatana will be available for purchase on 8 November 2019 at Gallery & Co., located at National Gallery Singapore, City Hall Wing, Level 1.

Footnotes

[1] Sutee Kunavichayanont & Luckana Kunavichayanont, “Those Dying Wishing to Stay, Those Living Preparing to Leave: The Art of Healing the Living and Relieving Souls of the Dead,” Tyler Rollins Fine Art, https://www.trfineart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Venice-Biennale.pdf (accessed 3 Sept 2019).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Emmanuel Torres, Tita Munõz & Hernando R. Ocampo, “An Interview with H.R. Ocampo,” Esso Silangan Magazine XI, 4 (1966): 10–1 , 15. Reproduced in Alice L. Coseteng, ed., Philippine Modern Art and its Critics (Manila: Unescoco National omission of the Philippines, 1972), 20.