Tough Job: Fieldnotes on Working Women in Development and the Environment

Who were the women in architectural history? Where were they working? What architectural activities were they engaged in? Why did they do the work they did? How was their work—writing, drawing, designing, managing, planning, reviewing, or building construction—perceived and valued? Asking these questions necessitates understanding the discourses, rhetoric, and circumstances—the systemic hierarchical imbalances and exclusions, constraints, and opportunities—that enframed women.

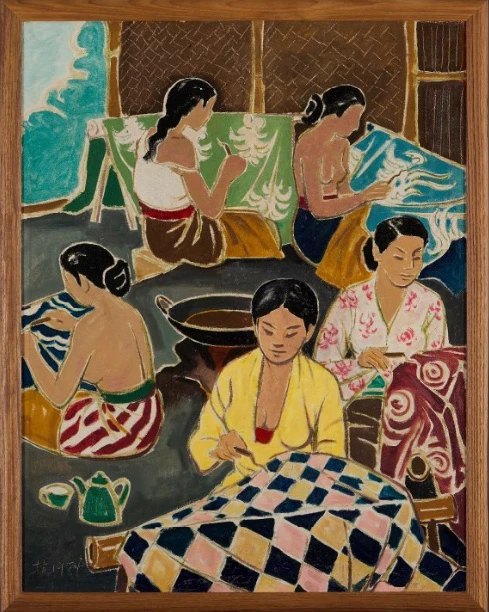

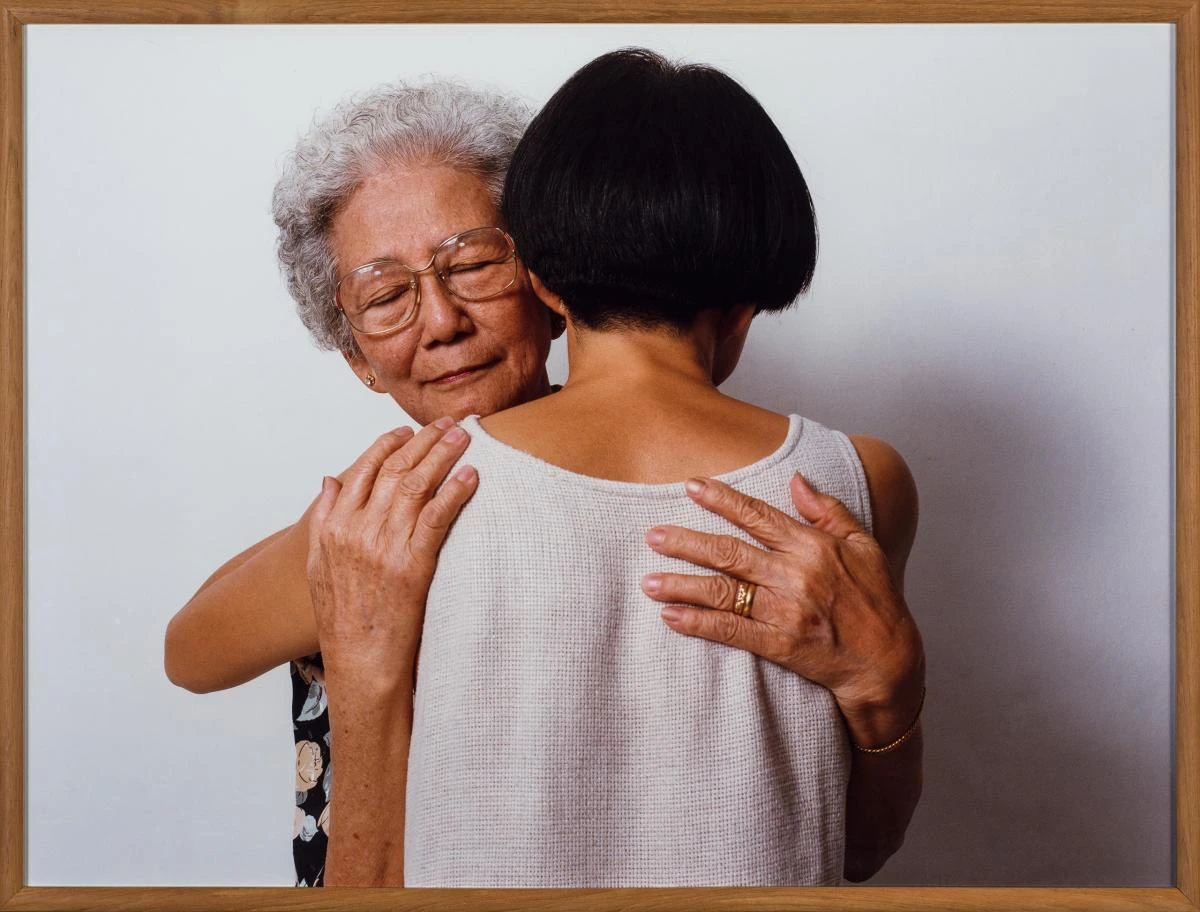

Hakka Family

1939

Oil on canvas

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Finding visual imagery of women workers is discovering a society’s attitudes on gender, equity, and the environment, its understanding of civic responsibilities, and aspirations of citizenship, which continues to reproduce the development discourse in the present. Their tenacious presence in the artworks asserts women’s agency amid modernity’s changing forms of work.

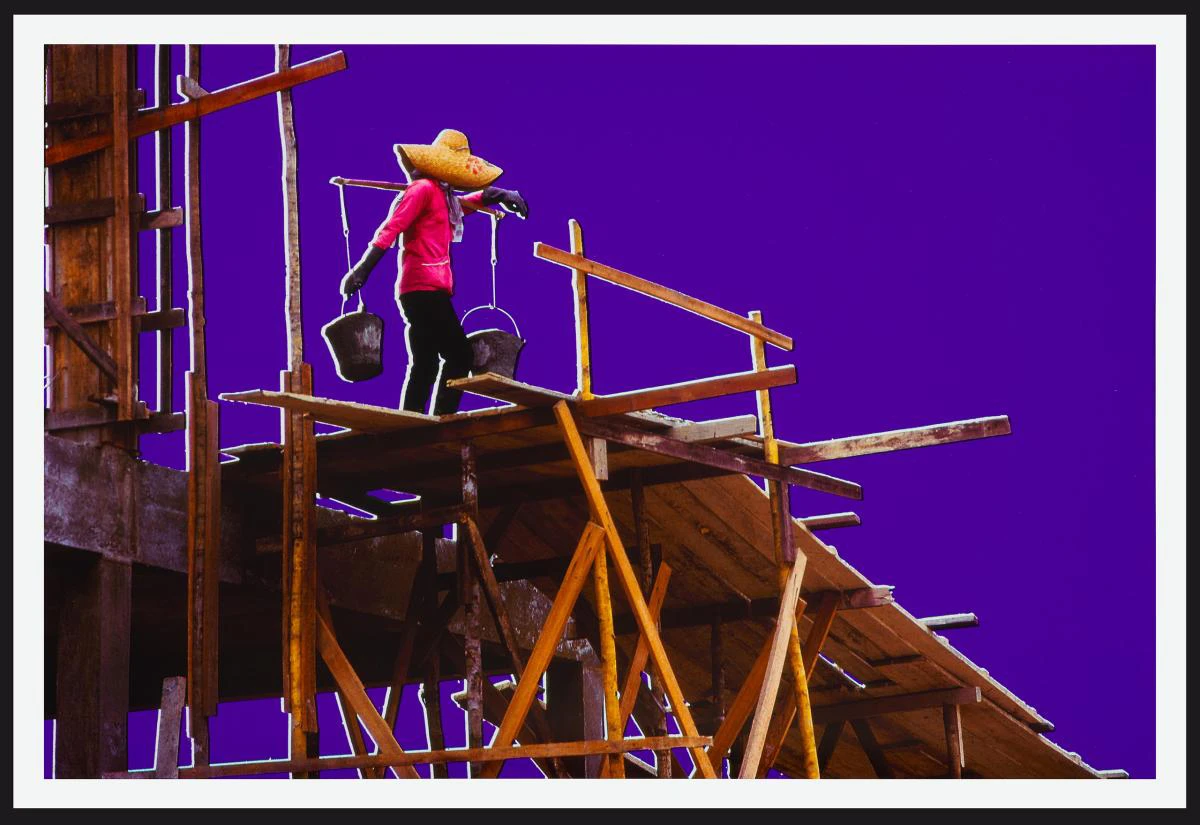

The lone worker stands at the top of a wooden platform. She balances a stick on her left shoulder. A thick string is tied to a metal bucket on each end, likely containing cement, bricks, or construction debris. Only she and those working at the construction site know the contents of the tin buckets. And perhaps her photographer, if he did approach her for permission to take her photograph. Set against a background of azure blue, the woman appears to be descending the makeshift wooden stairs nailed together by planks, a typical method of vertical access found at the lower levels of building sites. She is wearing a long-sleeved red jacket, black trousers, long black rubber gloves, and a straw hat with ribbon ties and a wide rim covering her entire face from view. By removing her surrounding context, the woman labourer becomes the main subject in this photographic artwork. Its title—Tough Job (1968)—acknowledges her labour. The partial wooden scaffold defines her workplace as the construction site. Her identity is inconsequential. Unnamed and faceless, her work defines her. (Figure 1)

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Standing before the photomontage, I asked the gallery sitter, “Is this a woman?” She told me that she had seen many women on construction sites with similar gait and dress when she was a child in the sixties. “This is not a woman.” I finally said out loud.1 “她肯定是女的,” she insisted but immediately said, “你们看艺术的可能有其他想法!”2 I smiled, not wishing to burden her with the hypothesis forming on the intersection of our image perception, knowledge of the subject, and the social realities of women and their experiences. In her critique of photography and the affective power of the photograph, Susan Sontag surmised that “photography’s program of realism” implies “the belief that reality is hidden” and “being hidden is something to be unveiled.”3 She purported that “whatever the camera records is a disclosure” of something otherwise imperceptible and fleeting or a “heightened reality” or another (“elliptical”) way of seeing. This woman, her work, and the work site are real. Her individual subjectivity is not.

In isolating the woman at work, thus heightening the act of construction labour, Tough Job condenses in a single vignette the situations of working women in the developmental city where their productive and reproductive labour were not understood or valued as work. Anthropologist Arturo Escobar highlights the exclusion of housewives, domestic servants, and indefinite categories, such as piece wage workers, by the World Bank mission of 1949 in its characterisation of Columbia’s rural population as an example of modern discourses’ refusal to acknowledge the productive work of women.4 He attributes this exclusion to the male bias of development and the model of agriculture in the United States where men are assumed to be the most productive workers. “To be more precise, he explains, “women’s visibility had been organized by techniques that consider only their role as producers,” despite women already participating fully in agricultural activities since early societies.5

In the postwar decades, also referred to as the Cold War era, the development framework categorised populations of territories in the world, particularly in the Asian, African, and South American continents as societies in transition.6 The industrial-development imperatives of the socialist state and the developing nations of the “Third World” saw women’s political mobilisation as they joined men in the workplace – at the farms, factories, and later offices. Their collective presence in conventional places of work made visible the slogan, “Women hold up half the sky.”7 At the same time, unequal treatment, expectations, and lesser attention given to female priorities continued. Within the modernisation approach to development, the logic of the “transitional society” argument implies that the modernising forces of industrialisation and urbanisation will automatically bring about improvements in the position of women, mainly through economic participation.8 It also implies that the end-state of this transitional process will be gender equality, a situation that sociologist Aline Wong argued is impossible within the assimilation model.9

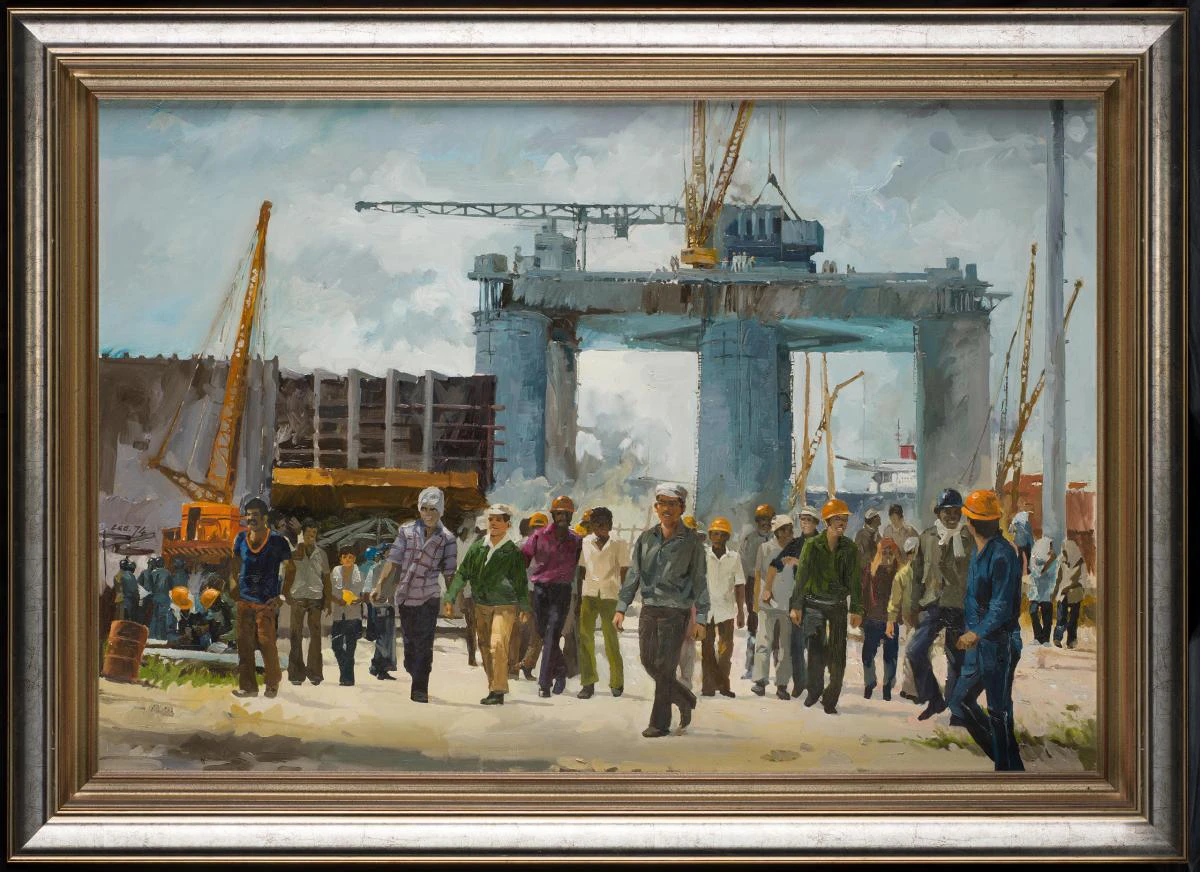

Working Women

Working women in the painterly scenes of 1970s Singapore embodied the contradictions of assimilation and equality. Diagonally across the gallery, three women wearing light-coloured scarves covering their heads and faces from the sun walk behind a large group of men, construction workers, and engineers Titled Shipyard (c. 1970s), the oil on canvas vignette of workers leaving a shipyard, behind them the gigantic gantry crane flanked by yellow tower cranes, and a partially complete building structure against a cloudy sky ‘gives form to worker solidarity’,” according to art historian Kevin Chua.10 (Figure 2)Chua identified a more profound affinity between the Equator Society and the Nanyang Style artists lay beneath a rejection of “Western” post-impressionistic style. Both groups spoke to a nascent public sphere that emerged in the late 1940s and early 1950s, opening a moment of “social possibility” that ended when the Equator Art Society closed in 1968. Artistic representations of this "social possibility" take the form of the industrious citizenry—workers in various industrial and urban situations—in this nation-building era. The type of worker and the type of work is recognisable. But the workers are anonymous, unlike Maurice Broomfield's photographs of men and women working in British factories in the fifties and sixties or Nick Hedges's photographic documentary of factory workers in the West Midlands in 1976.11 With faces concealed or out-of-focus, they are drawn with equal, if not lesser, detail than the urban landscapes they inhabit. Their identity is defined only by their work, which is invariably a tough job.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

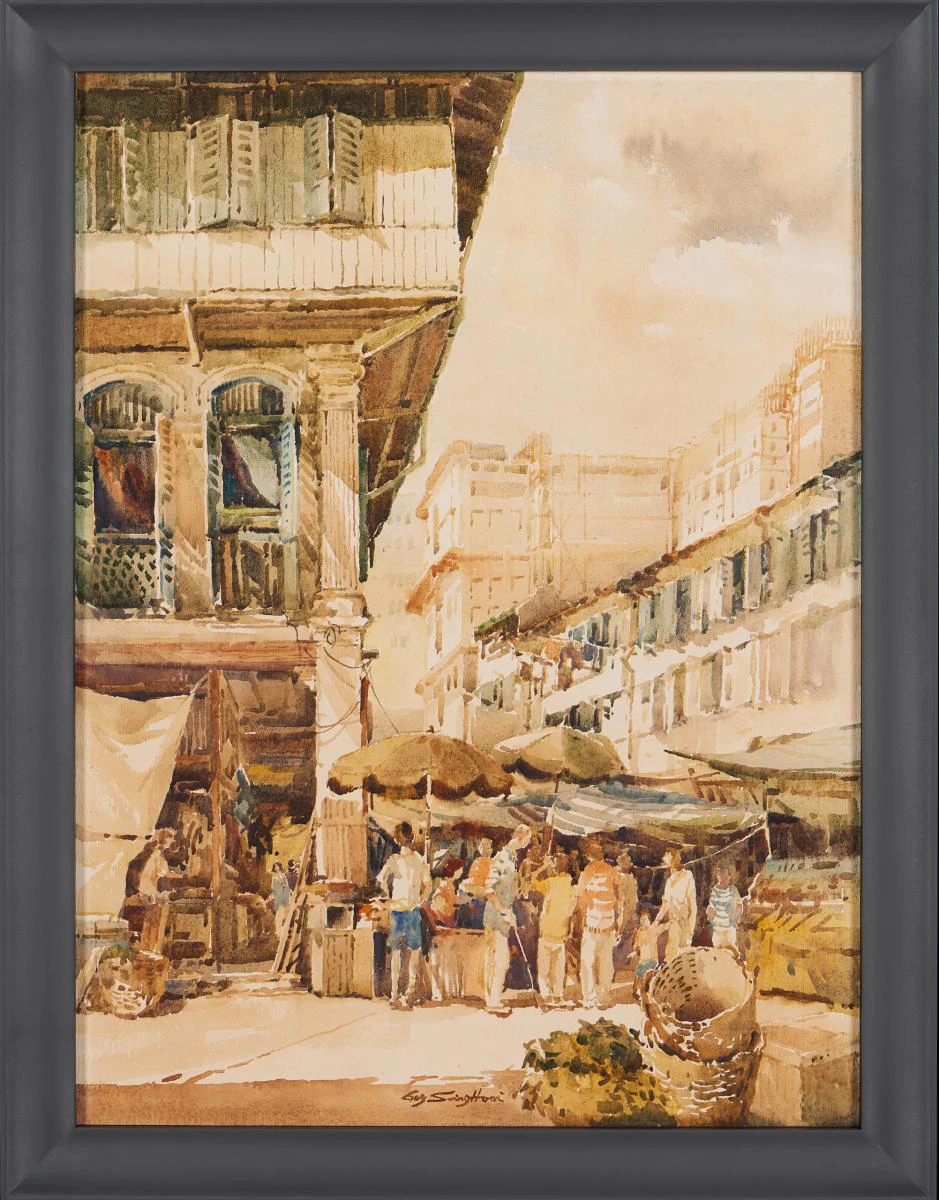

In contrast to the oil and watercolour paintings of industrialising Singapore, such as post-EAS works like Shipyard (c 1970s) and Construction of Sheares Bridge (1976), the paintings of the Balinese countryside depict the unhurried labour of the Balinese women performing domestic and agricultural work, “seemingly untainted by the specter of capitalism.”12 (Figure 3)

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

In 1952, the four artists—Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng—travelled to Bali—the “paradise of painters” close to home—in search of the painterly, when the island-province was becoming a tourist haven.13 The Singapore Standard’s brief coverage of the exhibition at the British Council in November 1953 pointed out “the sadness in the eyes” of the “Balinese Girl” as telling “the poverty of the Balinese subjects,” who were predominantly female.14 The excursion to the paradise close to home was gendered and exclusive. However, it was not unique to the Singaporean artists. The exotic portrayal of islands and women goes back to the nineteenth century and the entangled history of colonisation. In the 1920s, the Official Tourist Bureau of the Netherland Indies (established in 1909) issued a bi-monthly bulletin of information on travel to Java. Photographs of Balinese island life included in the guidebook Come to Java (1920) captured women at work in settings similar to the painted scenes by the Nanyang Style artists who visited over three decades later.15 (Figure 4)

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Georgette Chang-Chen, the one Nanyang-style woman artist, did not make the trip.16 Instead of the foreign gaze, her painterly ruminations on women’s production and reproduction were introspective, focusing on the familial. On display in the gallery is her 1939 Hakka Family, large oil on canvas of a woman breastfeeding her baby, and possibly her mother (the grandmother) feeding her daughter rice from a bowl with chopsticks. (Figure 5) The stove, the large sheltering hat, and the bamboo yoke are objects of labour. Within the frame, everyday work and reproductive labour coalesce.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

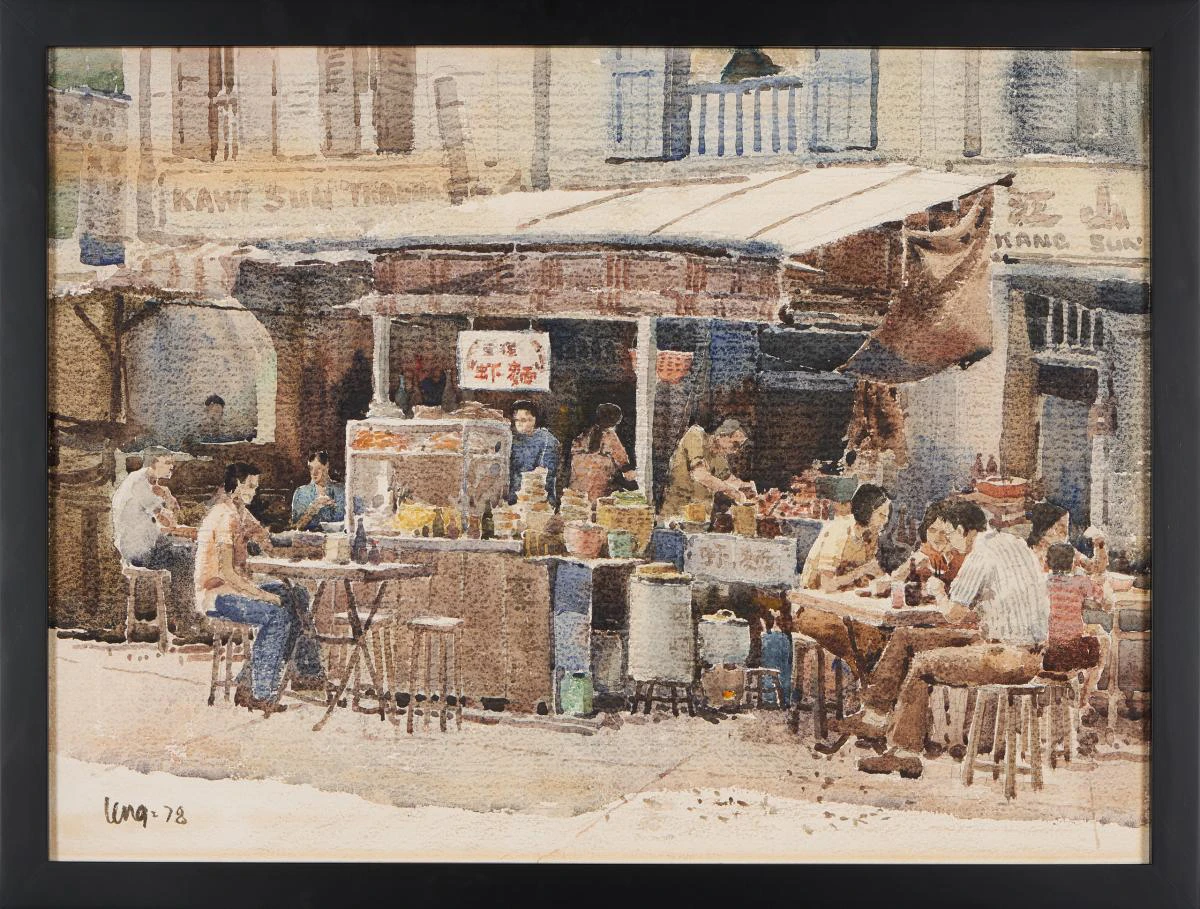

Back in Singapore, artists painted the kampongs and village life, where the rural, beyond the limits of the Central area, ceased to be a separate entity from the city in 1965. The kampong women were still subjects in the paintings in those years, though they appear more distant and in lesser detail. (Figures 6 and 7) It is worth noting that the women were all clothed at the height of the anti-yellow culture in the 1960s.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

In contrast to the rural idyllic depictions, the Equator Art Society artists painted day-to-day adversities experienced by the working class and individual identities during social upheavals. Urban surveillance and clearance under the rubric of improvement and social conflicts were frequent occurrences between 1946 and 1965.17 Amid the rapidly developing economy and urbanisation, the artists’ journey into the seemingly immutable space and time of the “village” belied the countryside and city as sites of struggle. As Singapore went from a Crown Colony to becoming a part of the Federation of Malaysia to an independent country, the Singapore Improvement Trust and later the Housing Development Board introduced their housing programs as “New Homes for Old.”18 “Slum clearance” and the “rehousing of slum-dwellers” became and continued to be the raison d’etre for urban renewal in the new nation well into the 1970s.19

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

From housework to piecework to construction, factory and office work, women worked on the frontlines of housing, urbanisation, and industrialisation. Between 1952 and 1957, the Balinese works directed the art viewer’s gaze toward Balinese rural life, domesticity, and environment. Back home, the types of work and spaces where women work were changing. The SIT employed a team of lady housing visitors—eighteen by 1957—to supervise tenancies, help control tenancy regulations, and advise tenants on general matters as they settled into their new Trust estate homes.20 Selected for their “energy, tact, forbearance and sympathetic approach” towards housing difficulties, women housing visitors were also engaged to check in on shophouses in the downtown Central areas to study the problem of overcrowding and over-subletting.21 Concurrently, women began speaking up on unequal wages and married medical practitioners were downgraded to temporary officers as soon as they were no longer single. At the height of public discourse on “Malayanization” (British policy on easing control to the disparate peoples who identified as Malayans), women doctors brought the issue of discrimination against married women to the Malayanization Commission.22 Female faculty members in the university encountered similar situations. In contrast, university committees debated the recruitment of female faculty members based on gender biases.23 On the eve of self-government, Singapore’s participation in the Afro-Asian Women Conference in Colombo in February 1958 marked a moment when female leadership and public representation in Singapore paved the way for the expanded role of women in the cultural, economic, and political development of the new nation. By 1960, social welfare, women’s emancipation, housing development and domestic life were intensely conflated and imbricated in the establishment of the HDB.24 Town planners prioritised the women and family needs in their planning of social amenities.25 Upon full independence in 1965, work and domesticity were radically reframed within the national housing schema and economic development.

Citizen Collectives

Women, as citizens, were called to “help the nation.”26 Those who could were urged to form a consolidated force in the interest of community services and nation-building to help others who could not help themselves.27 Art did not venture into those spaces. However, the paintings inadvertently confronted the everyday. The rural embodied by the kampong and the vivid etchings of urban life during a period of social and political awakening in the 1950s and 1960s gave way to industrial landscapes and construction sites in the 1970s, and the watercolour scenes of disappearing places and activities by the 1980s. They archived the urbanisation of nationalising Singapore as she transitioned from the initial phases of improvement and slum clearance to an island-wide urban redevelopment program. The women worked in the fields farming, construction sites building, trading, and hawking on the streets, and in the village washing, cleaning, cooking, and caretaking the children, the elderly, and the sick. Their workplace was urban, rural, industrial, agricultural, familial, and domestic.

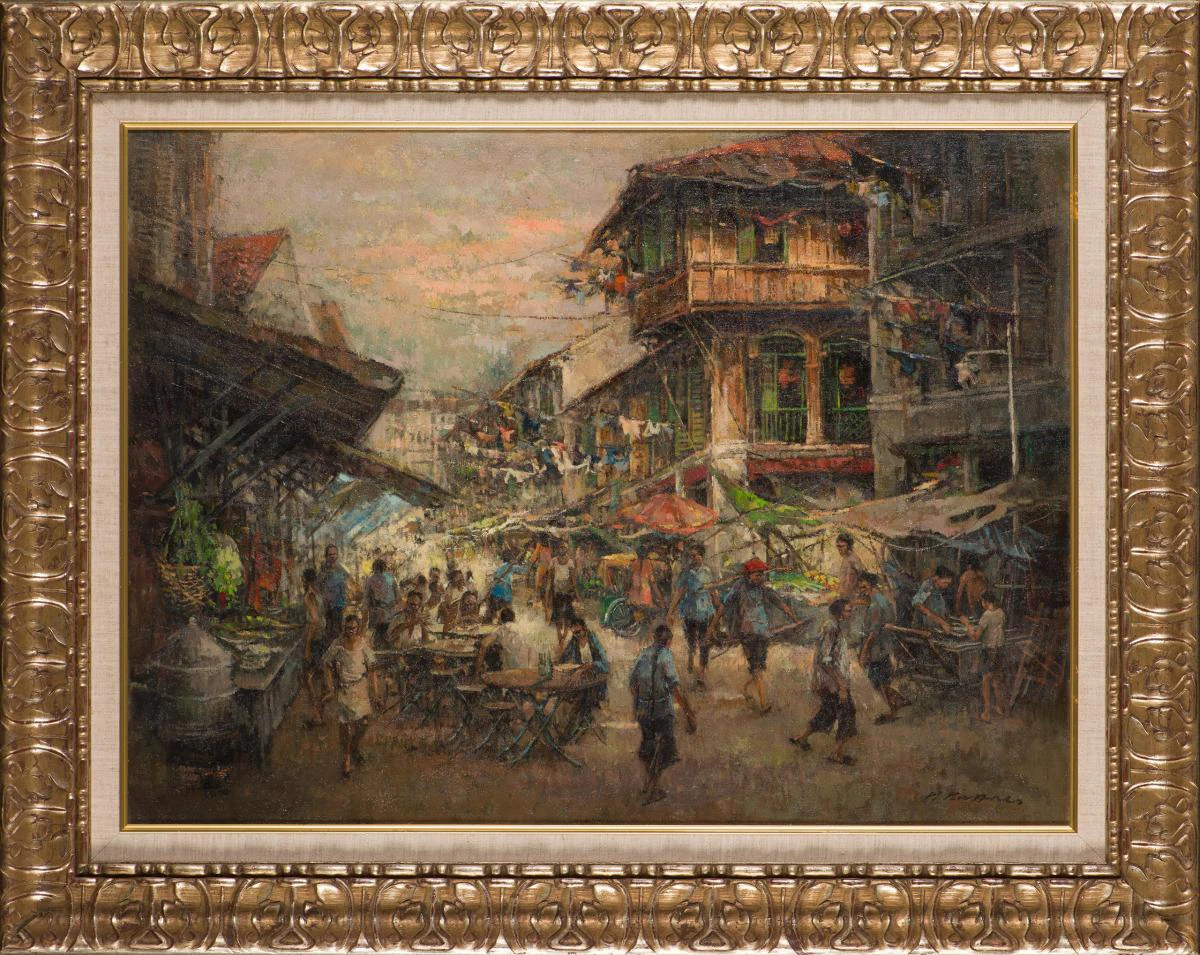

Everywhere, the women worked. In most of the artworks, the features of working women are undefined. In Tough Job (1968), the woman's face is hidden under the wide-brimmed hat or as paint smudges in the background, walking behind their male colleagues as they chat smilingly after a long day of work under the sun. In the 19th and early 20th century, most migrant working women from China were either girls and women who were trafficked as bondmaids (mui tsai) and prostitutes or independent single women fleeing poverty to find work in Singapore as labourers and domestic servants (amah). In the latter group, the resilient samsui women who began arriving in Singapore in the 1930s laboured into the 1970s. In the painting Temple Street (1970), a samsui woman in her distinctive red headgear carrying a wooden frame structure on her back walks past a vegetables and fruit stall. (Figure 8) Her face is tilted downwards. She has likely picked up ad-hoc work as a general day labourer from Upper Chin Chew Street nearby. Dressed in similar light blue samfoo and black pants, another samsui woman with a single long braid of black hair walks toward her. Her back faces the viewer. Without her headgear, she seems not to be at work. Two women and a man are busy behind a cooked food stall on Hokkien Street (1978). (Figure 9) A female hawker serves customers, including a woman with a young child, at a street junction in Chinatown (1980). (Figure 10) These paintings with women at work in urban and rural settings still focused on the essentialist concept of domesticity and conventional divisions of labour.28

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Recent exhibitions and commentaries on working women in art have expanded the repertoire to include women’s artworks and women workers beyond the familiar domestic settings to their participation in various sectors, including the industrial, health, economic, and education during peacetime and war.29 In a 1999 essay, political scientist Isabella Bakkar observed that several critical aspects of the globalisation process and “malestream” accounts of globalisation were occurring on a gendered terrain: Every institution, including markets and states, is constructing and reproducing various kinds of femininity and masculinity constituting an unequal gender order marked by a gender division of labour and structure.30 Bakkar notes that neoliberal policies, while celebrating “the genderless individual as an abstract commodity,” have also integrated large segments of women into labour markets increasingly described as feminized both in numbers and job characteristics.31 However, the visible sector of migrant domestic workers (MDW) and the near-invisible single-women households are not (yet) subjects explored in visual artworks.32

Development Subjectivities

In Gallery 3, Amanda Heng’s Another Woman (1996–1997), an introspection of her relationship with her mother and women’s positions in the Asian familial patriarchy, and Let’s Chat (1996) reflect on social domestic rituals through performance.33 (Figures 11 and 12) Heng’s Another Woman sidesteps the artistic convention of patriarchal portraiture in a minimalist take on her relationship with her mother through large format photographs of the two women, their bodies, and household items. Curators of the Care Collection selected Heng’s photographic exploration of independent womanhood and reclamation of mother-daughter ties under the theme, “Connection / Disconnection” as art therapy for healthcare workers during COVID-19.34 In Let’s Chat, the artist invited individuals from the public to sit and chat with her at a table while drinking tea and plucking the tips off beansprouts—an everyday activity in the kitchen among women in the household. By inviting the viewer to look closer, overhear, and participate in the conversations and reflection, the artist modified the familiar domestic scene.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Toward the end, the documentary and historical confront the literary and imagined in a counter-narrative to Singapore’s British colonial past as Utama – Every Name in History is I (2003) closes the three-gallery loop by “speaking back” to the framed portraits of family patriarchs and their wives. (Figure 13)

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

The largest and central painting of Diana, the Roman goddess of wild animals and hunt, accompanied by two handmaidens in toga-dress, is a counterpoint to the all-male cast in the founding narrative—no women were mentioned previously—and departs from the typical imagery of the female companion to the male figure of authority (think portraits of the King and Queen, Sultan and Sultana, and the governor and his wife). (Figure 14) The video with live actors faces the framed paintings of the characters across the gallery in a perpetual loop between the familiar and the enigmatic.35 Big, bright, and decontextualized, the photographic portraits of Another Woman and the painted portraits of Utama question the practices and narratives that have become socially accepted and ingrained. These, and the other post-1990s performances and mixed-media pieces, conclude the DBS Permanent Gallery art journey.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

The exhibition of the DBS Permanent Gallery, Siapa Nama Kamu? (What Is Your Name?), invites visitors to consider what it means to look at the Singapore story through its art and how it relates to the self and the community. Heng, in a 2010 interview for the National Arts Council award, said: “To live and to ask questions [have] become the most important things in my life.”36 This statement by the artist has come to define subsequent commentary of her work. The question remains: If the artists remain silent, or if the artist of an artwork is unknown, or if the work is untitled, what questions would the women who are represented and framed in various work situations—reproductive, domestic, and industrial—evoke? What would they tell us about our understanding of the societies and contexts within which they are placed and described in various situations of abstraction and detail?

The different curatorial labours to recuperate women’s works within recent exhibition settings have been necessary interventions and starting points for a more inclusive and complex account of Singapore art. Nevertheless, discussions on the presence of women in art, if any, are primarily directed toward an individual work or artist or genre. Just as it is pertinent to address the whys and wherefores around the past exclusions and indifferences towards women’s practices and subsequent appearance in national art histories, so does the visualisation of women in works of art situate them in the changing contexts of Singapore. Post-war Singapore was a process of overlapping displacements that saw the transformation of the living and working spaces, conditions, and practices brought about by decolonisation and nationalisation. In Encountering Development, Escobar emphasises how development brings people into discourse by consigning them to fields of vision through “a process of enframing that turned them into spectacles.”37 Art offers a way out of the enframing by showing (Sontag) and, pertinently, asking questions (Heng). Who is she? What is she doing? Where is she? What is her expression, dress, and posture? Reading working women in the artworks offers a window to understanding their agency amid modernity’s changing forms of work.

Inquiry as Project

The one-day visit to the National Gallery Singapore reflects on the project I began in 2017 to map the contours of feminist agency in the built environment. Who were the women in architectural history? Where were they working? What architectural activities were they engaged in? Why did they do the work they did? How was their work—writing, drawing, designing, managing, planning, reviewing, or building construction—perceived and valued? Asking these questions necessitates understanding the discourses, rhetoric, and circumstances—the systemic hierarchical imbalances and exclusions, constraints, and opportunities—that enframed women.

In a perpetual state of construction, the archive-in-progress encompasses the relationships between individuals, groups, institutions, affiliations, events, publications, places, buildings, and objects enframed within the development rationale, which, since 1949, defined the “Third World” inclusive of the whole of Asia and its diverse people as in need of improvement.38 Beginning with the triad activity of finding, questioning, and naming, I discover economically active women inhabiting and working in the public and domestic spheres in the artworks. Whether impressionistic or realistic, the artists’ depictions of the scenes with the objects and people amidst the changing landscapes of Singapore place within the frame of women’s public and economic participation throughout the twentieth century.

From the 1950s, the artworks with women foreground an epistemological break in our understanding of the world when the majority of people became “underdeveloped” in what Arturo Escobar and Gustavo Esteva described as “the era of development.” Then women took on singular recognizable roles as homemakers (“mother,” “grandmother,” “amah” or “maid”), peasants (“Bali girls” personifying cheap, docile labour in agricultural activities such as picking fruit, shelling nuts, or spinning cotton), or “factory girls.”39 This singular framing of women’s work reinforces Susan Sontag’s point on the unequal footing of women participating in modern work as the world tends to reproduce their image as “‘household’ (serving and nurturing) creatures” and “considered unfit for large executive responsibilities.”40 She emphasised, “women cannot be said to be economically liberated until they perform all activities now performed by men, on the same terms (with respect to wages, standards of performance, exposure to risk) as men – thereby relinquishing the prerogatives of the fool, the child, and the servant.”41

The post-pandemic reopening of museums and archives drew renewed attention to colonialism, class, race, and gender, and research scholarship on women’s labour, focusing on specific periods and areas in the world.42 As we learn more about women artists and their works, the visual representation of women and working women, we are identifying inclusions, exclusions, and the persistent visual rhetoric of women and their work in art.43 Through in-person and virtual exhibitions, courses, talks, and publications, we discover the geographies and institutions that host these discourses, and the privileges of being their audience and participants.44 Apropos of finding working women in art—from the worker in the fields to the itinerant construction labourer and street hawker to the artist performing her work as her art—a triad visual-intellectual process of searching, questioning and translating is necessary to emancipate women and their labour from the flattening effects of development.

Finding Working Women in the Singapore Art Collection

All artworks are from the collection of National Gallery Singapore. Images courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

The author wishes to acknowledge Amelia P. Ee and Ella L. Wee for their research efforts, and Ada Wu for the video editing.

This work is supported by the Research Grants Council (HK) GRF Fund [Project number: 17608622].

For transcript of the video, click here.

Notes

- This statement is in reference to René Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, which in this case, would be Ce n’est pas une femme.

- English translation: “She is definitely a woman… You, art viewers, may have a different idea.”

- Susan Sontag. “Photographic Evangels,” in On Photography. (London: Penguin, 2008; c1977), 120.

- Arturo Escobar, “Power and Visibility: Tales of Peasants, Women, and the Environment,” in Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 171–172.

- Ibid., 172. Referring to “industrialization, agriculture, peasants, women, and the environment,” Escobar identifies development as “discursive practice,” which seems disconnected, yet highly visible and visibly reproducible. An example can be found in Kumari Jayawardena’s study on women’s rights in Java, where until the 19th century, agricultural occupation in traditional societies always provided a specific place for the labour of women. Kumari Jayawardena. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World (London: Zed Books, 1994), 138–139.

- Clifford Geertz, Old Societies and New States: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa. (New York: Free Press, 1963).

- The sloganisation of this old Chinese saying is attributed to Mao Zedong —though there is no evidence that he actually said this—during the Cultural Revolution, between 1966 until his death in 1976, where the political and social changes he implemented included the promotion of women’s rights, particularly their participation in the work force. “Woman hold up half the sky” is also the title of the manifesto-speech by Michael Klonsky, the Chairman of the October League International Women’s Day celebration in Los Angeles on March 11, 1972. By the mid-1970s, women’s rights issues drew much more attention among civic, professional, academic and media circles in Singapore. Between November 1974 and January 1975, the Sunday Times published a series of articles under the heading, “I am Woman” by Hsin Nu-Ren (Wade Giles spelling for “New Woman”), after which the phrase “I am Woman” continued to be used into the 1980s. “Making the best of Women's Year,” The Straits Times, 5 January 1975. Mei-lin Chew, one of 18 members of the Singapore Press Club who went to China for a seventeen-day goodwill and education tour in 1977, was told at a factory visit that women were politically and economically equal. Mei-lin Chew, “Women in China,” The Straits Times, 8 December 1977.

- Peggy Antrobus and Linda Christiansen-Ruffman. “Women Organizing Locally and Globally: Development Strategies, Feminist Perspectives,” in Feminists Doing Development: A Practical Critique, ed.Marilyn Porter and Ellen Judd (New York: Zed Books, 1999), 177–78.

- Aline Kan-Wong, Women as a minority group in Singapore, Working Series No. 29 (Singapore: Dept. of Sociology, University of Singapore, 1974), 4–5. Wong advocated action by women’s groups and state intervention. In April 1975, she gave a talk titled “I am Woman” at the National Library in conjunction with International Women’s Year. She was among the first women members of parliament in 1984 and became chairperson of the Housing Development Board between 2003 and 2007. She saw the lack of awareness of their minority group status among women evident in the existence of few women’s organization for the purpose of fighting for gender equality in Singapore society in the 1970s. Wong, Women as a minority group in Singapore, 8.

- Kevin Chua. “Painting the Nanyang’s Public: Notes Toward A Reassessment,” In Eye of the Beholder: Reception, Audience, and Practice of Modern Asian Art, ed.John Clark, Maurizio Peleggi, and T.K. Sabapathy. (Sydney: Wild Peony, 2006), 73. Identifying that the artist and other members of the Equator Society rejected the “Western” post-impressionistic style and abstract tendencies of the Nanyang artists in a plea for art that “help uphold our national dignity and to help in current nation building,” Chua identified a more profound affinity between the two collectives lay beneath that rejection.

- “White Heat: Factory Workers of the 50s and 60s,” The Guardian, 14 March 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2019/mar/14/maurice-broomfield-white-heat-photography-production-line-factory-workers

- The output of the pilgrimage to Bali made by Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, and Liu Kang in 1952 that were exhibited at the British Council in 1953.

- “4 Artists Hold Bali Art Show.” Singapore Standard, 10 November 1953, 2. Kevin Chua describes this as the middle-class in Singapore needing “such a redemptive notion of paradise.” By the 1950s, Bali was known as a “magical island” that were attracting European settlers, especially artists and painters. See, “The Magic of Bali,” The Singapore Free Press, 2 July 1953, 4; and Elizabeth E. Marcos, “This is Bali,” The Straits Times, 23 February 1950, 11.

- Ibid.

- Officieel Toeristenbureau voor Nederlandsch-Indie. “Island of Bali - Weaving” (p. 40), “Island of Bali – Native types” (p. 252), “Island of Bali – Types of Women” (p. 280), “Island of Bali – Type of Woman” (p. 288), in Surabaya, photographs by Kurkdjian, 1900/1919. In: Come to Java Information for Travellers, with Two Maps. Trips in the Isle of Java. Batavia: Printed by G. Kolff, 1920. Southeast Asia Visions: John M. Echols Collections, Cornell University Library. In 1950, journalists like London Times’ correspondents Ian Morrison and Hugh Astor, and Elizabeth Marcos who wrote for the Straits Times, travelled to Bali to report on its culture and people. Marcos wrote a long piece on the Dutch artist Jan le Meyeur de Merpres who lived on the island for 17 years, describing how his wife and model-muse, Pollock, was “synonymous to the grace, exotic color and earthly beauty that characterizes” his work. Elizabeth E. Marcos. “This is Bali,” The Straits Times, 23 February 1950, 11.

- Her maiden name was Chang Li Ying or Zhang Liying (pinyin). She kept her married name Mrs Chen from her marriage to Eugene Chen, a lawyer and China’s foreign minister in the 1920s, which lasted from 1930 to his death in 1944.

- See, “Police Quell Near Riot By Squatters.” Singapore Standard, 21 February 1952, 1. Several riots occurred during this period, bookended by the Maria Hertogh riots in 1950 and the racial riots in 1964, which suffered the greatest number of casualties.

- “New Homes for Old – Clearing the slums in Singapore,” The Straits Times, 3 May 1936, 14; “New Homes for Old,” The Straits Times, April 6, 1947, 6; “New Homes for Old Soon,” The Straits Times, September 26, 1948, 3; Anson Sewell, “New Homes for Old,” The Straits Times Annual, January 1, 1953, 48–49; “New Homes for Old,” The Straits Times, June 2, 1961, 8.

- “Singapore Housing,” The Straits Times, 23 August 1918, 9; “Singapore Housing: Report of the Government Commission - The Death-Rate and the Congested Areas,” The Straits Budget, 30 August 1918, 15; “Housing and the Health of Singapore,” The Straits Budget, 20 October 1927, 13; “Housing of the Population of Singapore,” The Straits Budget, 11 November 1926, 9. Raymond Lim in an article titled, “Let’s Be Rational on Housing,” New Nation, 2 March 1974, 7, commented on the expulsion of five opposition members of parliament and the detention of eight others on grounds of violating the Internal Security Act, threatening to incite racial violence, and their involvement in radical anti-national activities.”

- “The Trust And Its Tenants,” The Straits Times, 24 December 1954, 6; “Nosey Parkers' win tenants' help and co-operation,” The Straits Times, 28 April 1957, 9.

- “Jobs need tact – so girls will get them,” The Straits Times, 9 January 1957, 5.

- “Malayanization Of The Civil Service,” Singapore Standard, 22 August 1952, 6; “Work and Marriage,” Singapore Standard, 22 November 1955.

- “Split in University Varsity Over Recruitment of Academic Staff,” Singapore Standard, 18 October 1956.

- Seng, E. “Multiple Domesticities versus Homogenising Difference,”. In Multiple Modernities in Asia. (Singapore: Asia Urban Lab, 2018), 183–194.

- “Integrated Planning,” The Straits Times, 27 February 1962, 10.

- “'Help nation' call to S'pore women,” The Straits Times, 26 August 1965, 4; See, Seow Peck Leng, “Report on new Life in New Homes,” 7. In Persatuan Wanita Singapura. Singapore, 1965.

- “Form Consolidated Force, Local Women Urged,” Eastern Sun, 30 December 1968; “Women can do much more,” New Nation, 12 April 1971, 11; “Women power here untapped,” New Nation, 3 May 1971, 11. “How would you like to see your grandma end up like this?” New Nation, 18 October 1974, 12/13.

- Juan Hugo described “The Division of Labor: 'Women's Work' in Contemporary Art” exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1996 as still hovering around the essentialist concept of domesticity, focusing on the conventional division of labor including the range of domestic skills from cleaning, cooking, washing, child-rearing, and management of the household to sewing, weaving, embroidering, and other narrowly defined processes. Juan Hugo, “Reviews,” Frieze, 26 (1 September 1996).

- Some examples: Fisun Güner, “From kitchen slaves to industrial workers – the superwomen of Soviet art,” The Guardian, 13 June 2016. “Women’s Work” exhibition, Lyndhurst, New York, 26 May to 26 September 2022.

- Isabella Bakker, “The New Global Architecture, Gender and Development,” in Feminists Doing Development: A Practical Critique, ed. Marilyn Porter and Ellen Judd (New York: Zed Books, 1999), 207.

- Ibid.

- Four decades after “Women as a Minority Group in Singapore,” Lilian Chee’s conceptualisation of 03-Flats, a 2014 film that documents the everyday lives of single women occupants in Singapore’s public housing, is one of the few works to-date speaking directly to Wong’s inquiry on immigration, development, and assimilation. Conceptualised by Lilian Chee and directed by Lei Yuan Bin, 03-Flats was released in October 2014 and screened at the Venice 15th International Architecture Biennale in 2016.

- Both works belong to the Collection of the Singapore Art Museum.

- Caring through the Arts by National Gallery Singapore and Singapore Art Museum, https://www.nationalgallery.sg/content/care-collection#:~:text=Another%20Woman%20is%20Amanda%20Heng's,within%20the%20traditional%20Chinese%20family. The other works under the same theme include Ezzam Rahman’s Here’s who I am, I am what you see (2015), and Sarah Choo Jing’s The Hidden Dimension II (2013).

- Sontag describes the dialectical gaze through photojournalist Dorothea Lange’s work: “Just to show something, anything, in the photographic view is to show that it is hidden. However, photographers do not need to point out the mystery with exotic or exceptionally striking subjects. When Dorothea Lange urges her colleagues to concentrate on ‘the familiar,’ it is with the understanding that the familiar, rendered by a sensitive use of the camera, will thereby become mysterious.” Susan Sontag. “Photographic Evangels,” in On Photography. (London: Penguin, 2008; c1977), 121.

- Amanda Heng, NAC Arts Awards 2010 interview, https://youtu.be/58S9b3Sw7fM?feature=shared.

- Arturo Escobar. “Power and Visibility: Tales of Peasants, Women, and the Environment.” 156. In Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011). “The god trick of seeing everything from nowhere” is taken from Donna Harraway’s “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- Arturo Escobar. “Planning,” 148–150. In The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, ed. Wolfgang Sachs (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2019).

- Esteva Gustavo. “Development,” 1–2. In Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, edited by Wolfgang Sachs (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2019). Beyond the rural, Aihwa Ong’s study of newly urbanized women factory workers in Malaysia examines the production of young women factory workers as “docile bodies” through systematic forms of discipline in the factory and outside, and how they protested against labor control and male discipline in the new industrialized conditions. Aihwa Ong. Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline (Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press, 1987), 221.

- Susan Sontag, “The Third World of Women” (1972), 54–55. In On Women, ed. (London: Blackwell, 2023.

- Ibid.

- Kinnahan, Linda Arbaugh. “Portraits of Working Women: Lola Ridge’s ‘The Ghetto’ and the Visual Record.” Humanities (Basel) 11, no. 117 (2022). An earlier book by Kristina Huneault examines working women in Victorian Edwardian Britain and the confrontations between the cultural meanings of labor and conventional ideologies of femininity, gender and class, selfhood and otherness, domesticity and the city. Huneault, Kristina. Difficult Subjects: Working Women and Visual Culture, Britain 1880–1914. (Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate Pub, 2002).

- Jane Howard argues that since there is “a lot of bad art by men,” including more “bad art” by women will not make the world of art worse but would achieve gender parity. Jane Howard. “All I want to see is more bad art by women. Give someone else a chance to fail,” 1 November 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/nov/01/all-i-want-to-see-is-more-bad-art-by-women-give-someone-else-a-chance-to-fail. Christina Y. Z. Chung, “Gendering Her Art: The Category of ‘Woman’ In the Art History of Hong Kong,” Asia Art Archive, https://aaa.org.hk/en/like-a-fever/like-a-fever/gendering-her-art-the-category-of-woman-in-the-art-history-of-hong-kong

- For example, the V&A organizes a selection of “powerful and pioneering women” from their collection and offers courses (Women Artists in Britain, 1750-2000), podcast talks by and on female artists, and awards. See also, Alex Greenberger, “Women Artists, Black Figures, and Modern Art Enter the Met’s European Painting Galleries in a Bold New Hang,” ARTnews, 20 November 2023. “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800,” Baltimore Museum of Art, October 1, 2023–January 7, 2024. The Metropolitan Museum invited contemporary artists to reflect on their art in a two-part Women’s Work series in March 2023. Ann C. Collins, “Women’s Work, Parts I and 2,” The MET, 3 and 20 March 2023.