Tracing Southeast Asian Artists in Paris: Report on a Curatorial Research Project

For many artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, Paris was a place of pilgrimage. In this curatorial insight, trace the journeys of and connections between Southeast Asian artists who made a stop in city, through curators Lisa Horikawa and Phoebe Scott's methodological report.

Detail of Harmony in Green: The Two Sisters

(Harmonie Verte: Les Deux Sœurs),

c. 1938.

77.0 x 68.0 cm

Gouache on silk

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Introduction

For many artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, Paris was a place of pilgrimage. The city offered opportunities for training in art—both formal and informal—as well as an unmatched variety of sites for exhibition through its many annual salons, commercial galleries and exhibiting societies.[1] At its peak, it also offered access to an international network, as artists from all over the world met in its ateliers. For these reasons, Paris is often described as an “art centre”: but what does this really mean? For the artists from Southeast Asia who travelled to and studied in Paris, what impact did the city really have, and what types of engagements and activities was it possible for them to access? As a preliminary step towards answering some of these questions, this project sought basic information about the activities of Southeast Asian artists in Paris from 1880 to 1960. It was intended as a broad, sweeping exercise to collect foundational data to form a basis for future analysis, and provide a resource for other scholars in the region. The project complements some of the existing research in this area: for example, research exhibitions relating to Southeast Asian artists in Paris organised along national lines in Singapore and Malaysia.[2] There are also individual monographic studies on Southeast Asian artists who spent extensive periods in Paris: for example, the Indonesian artist Salim (b. 1908 – d. 2008) and Nena Saguil (b. 1914 – d. 1994) of the Philippines.[3] The shorter “Paris periods” of specific artists are also covered in monographs, for example, for Juan Luna (b. 1857 – d. 1899) or Georgette Chen (b. circa 1906 – d. 1993)..[4] In general, however, there has been a lack of specific information and reliable source material in this area; this has posed a challenge to forming a complete picture of the activities of Southeast Asian artists as a collective group. In addition, without a clear understanding of what the activities of these artists really were, it is tempting to fall back on generalisations or totalising claims about “French influence” or “Paris as centre.”

In the hope of addressing these gaps, we set out to compile reliable information through a broad data collection project focusing on two general strands of information: where artists studied in Paris, and whether they showed in Salon exhibitions (or other documented public exhibition sites, depending on the availability of records). We selected these two strands in particular on the basis that they would capture the activity of a large number of artists, whilst representing well-documented sites with publicly-available records in libraries and archives. The scope of the research was limited to 1880–1960. For the period before 1880, we thought records for Southeast Asian artists in Paris would be too limited and exceptional to seek out at this stage of research; for the period after 1960, we felt the information was readily available and could still be sought from living artists.

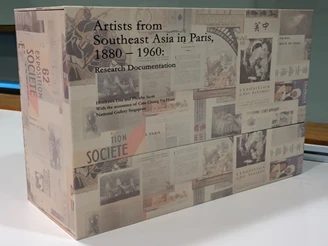

This brief report traces some of the steps we took in unearthing these records at various research sites over four weeks in Paris. We note the scope, limitations and challenges of our research, as well as some of the general findings. The full research report produced for this project, as well as the comprehensive index of records from Southeast Asian artists at different art schools and salons, can be accessed in the Rotunda Library & Archive of National Gallery Singapore (figure 1).[5]

Research Sites

Students of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts

One of our most important areas for research was the enrolment records for artists studying at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (ENSBA), Paris. The longest-running French teaching institution in the fine arts, ENSBA provided training in painting, sculpture, engraving and architecture (later discontinued), rooted in the artistic canons of the Western classical past. The academic training of ENSBA was based on a strict programme, in which drawing formed the main foundation. While modernist artists were often opposed to the conservative and classical mode of training here, it remained an important educational site throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. While it was known that many Southeast Asian artists passed through the studios of ENSBA, we were keen to find more detailed records about their time there, as well as to unearth new records of previously undiscovered or little-known artists. Fortunately, very extensive archives relating to ENSBA still exist, now conserved in the French Archives Nationales (the French national archives), at their Pierrefitte-sur-Seine site on the outskirts of Paris (figure 2). The AJ/52 series of documents contains detailed records of the School’s internal functioning, including requests for admission, enrollments, class lists for individual ateliers, and results in competitions and examinations.[6]

However, finding Southeast Asian artists in these records was not straightforward, and required several weeks of painstaking manual searches. This was partly due to the tiered system of admissions to ENSBA. While some students were officially admitted, and sat for regular, formal examinations until their graduation, other students studied more informally via shorter-term admissions to specific ateliers. Only students who were enrolled formally have individual dossiers, which are now searchable by name via digitized archives. This was the case for very few Southeast Asian artists: one notable exception was the 19th-century Vietnamese artist Lê Văn Miến (1874–1943), who was enrolled in the atelier of well-known academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) in the early 1890s.[7]

Many other traveling artists who visited Paris for a few years or less would instead apply to an individual professor of ENSBA for permission to follow courses in their studio on an informal basis. Finding the records for these students involved a lot more detective work and patient deciphering of handwritten records. However, their presence at ENSBA could be traced through chronological and alphabetical enrolment registers, dating from the 19th century to the 1950s.[8] These records allowed us to see in which ateliers the students appeared, and for how long. The disadvantage was that these minimal records provide no other information about the students’ work, and do not identify any details about their background. Identifying the Southeast Asian students necessarily required us to make some educated guesses based on students’ names and also involved reading the entire registration record for the period to search for potentially relevant students! Fortunately, another section of the archives contained files specifically dealing with enrolment requests by foreign students (often written to the ENSBA administration by foreign embassies). It was here that we could cross-check further records about the students’ background and origins, and sometimes how their studies in Paris were funded.[9]

Based on our findings, we confirmed that there was not an even geographic spread across the region: of the 54 individual artist records of students who studied or requested to study at the ENSBA, the largest share came from Vietnam (27 artists), followed by Thailand (6), Philippines (4), Singapore (5), Malaysia (2) Cambodia (2) and Myanmar (1) and Indonesia (1). Vietnam’s historical colonial connections no doubt contributed to its high number. One of the interesting outcomes of using such fine-grained records as individual atelier class rolls is that it revealed how certain studios were more open to foreign students, and simultaneously hosted a number of students from Asia. For example, Gérôme’s studio in the early 1890s hosted not only Lê Văn Miến, but also another Vietnamese artist Nguyễn Trang Thúc, and an artist from Siam, listed as Nai Chib. Such previously-unknown connections may merit further investigation and research. Another interesting area to note for future research is Chinese artists with strong connections with Southeast Asia. For example, Zhou Bichu, Guo Yingling and Gao Peize, whose names were recorded in various ateliers of ENSBA between the late 1920s to early 1930s, later developed connections with art circles in Indonesia, Philippines or Singapore. The activities of such migrant Chinese artists remain peripheral in art historical writings of both China or these Southeast Asian countries. Findings from this research project open up the opportunity to re-examine the possible wider network and connections at work.

Artists Exhibiting at the Paris Salons

The other significant area in which we concentrated our research efforts was in records relating to salon exhibitions in Paris. Salon exhibitions refer to regular (generally annual) large-scale public art exhibitions, for which artists could submit work for consideration. Usually, works submitted to salon exhibitions were assessed by a jury. The advantage to artists of these exhibitions was that their work could be exhibited and sold to a broad public, without relations with a commercial dealer (a relationship that could be difficult for a young or visiting artist to establish). Salon catalogues often published the artist’s address to facilitate direct sales.[10] Salon exhibitions were also widely reviewed in the press, which meant that an emerging artist could attract critical attention for their work. It should be noted that by the 1920s, most activity of the modernist avant-garde was no longer concentrated in the salons, and instead tended to be represented in smaller commercial galleries: however, salon exhibitions still accounted for a large volume of artistic activity in Paris at the time.

By the early decades of the 20th century, there were a number of different salons in Paris, each with a different history and orientation. The oldest and longest-running salon was the Salon de la Société des Artistes Français (Salon of the Society of French Artists). This salon was strongly connected to the art academy and had a reputation for conservatism. By the mid-19th century, artists had begun to reject the conservative values of this salon and its entrenched hierarchies, and establish alternative exhibiting salons to break its monopoly (such as the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts).[12] The Salon des Indépendants, particularly associated with the Impressionist painters, was especially radical for entirely dispensing with the jury system.[13] In the 20th century, these salons were again displaced by younger, newer salons, such as the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Tuileries, which aimed to celebrate the work of young and emerging artists. In addition, Paris also hosted regular salons on more specialised subjects, such as the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Salon of French Orientalist Painters), the Salon of the Société Coloniale des Artistes Français (Salon of the Colonial Society of French Artists) and the Salons of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (Salon of the Society of Decorative Artists).

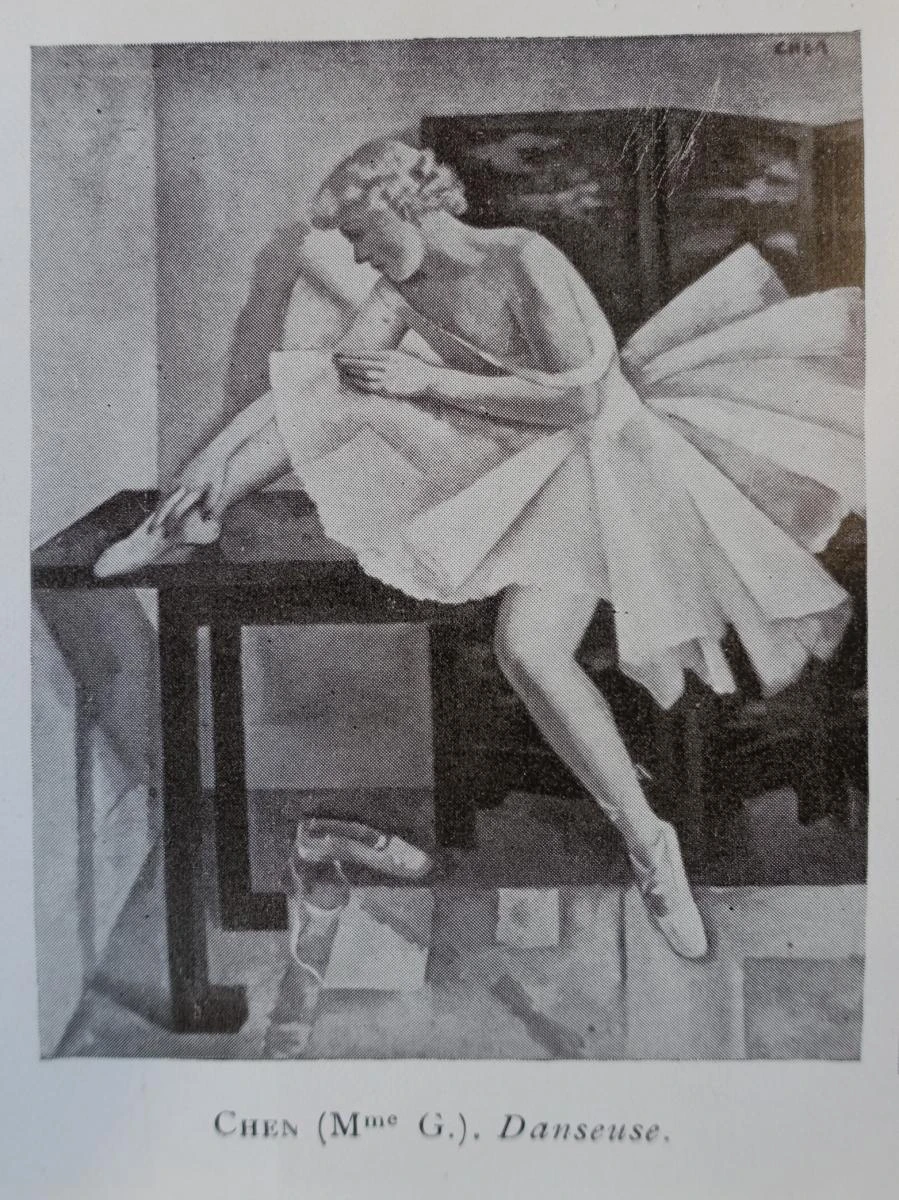

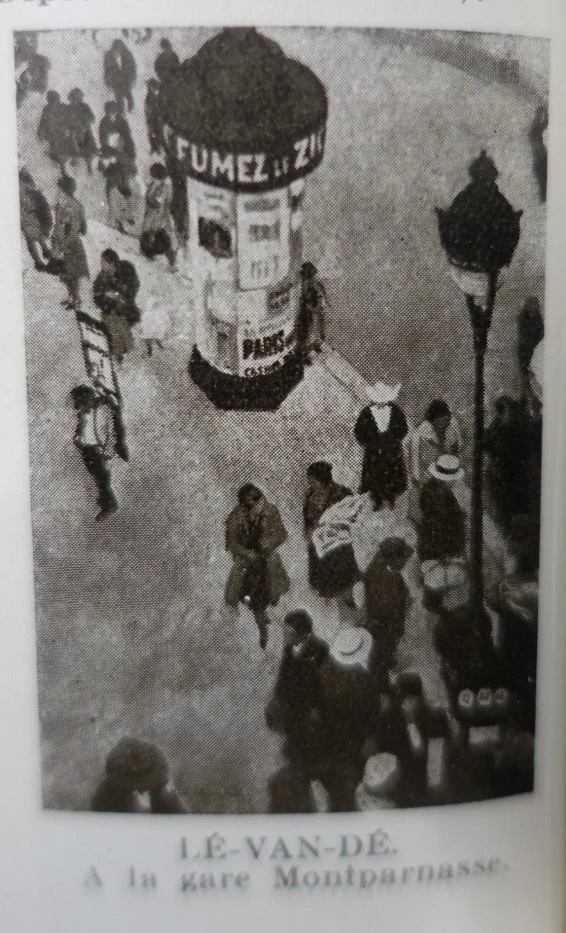

Works by artists from or associated with Southeast Asia appeared in all the salons for the period that we studied. One of the advantages of researching salon exhibitions is that they tend to be very well documented: for each exhibition, a catalogue was normally published. It would list the artists, artwork titles, artist’s address and sometimes even their country of origin and teacher. In addition, many of these catalogues have already been comprehensively indexed and consolidated, especially for their more important time periods, in a very useful series of books edited by Dominique Lobstein and Pierre Sanchez.[14] These books allowed us to search more rapidly, by artists’ names. However, searching individually in the original catalogues, although more painstaking and slower than reviewing the consolidated index, did yield some special results. For example, sometimes the salon catalogues would publish images of the exhibited works: as a result, we were able to find images of previously unknown artworks, for example by Georgette Chen (figure 3) and Lê Van Dê (figure 4). Looking at the original catalogues also allowed us to see unexpected connections between artists: for example, the Salon d’Automne catalogue of 1949 reveals several Vietnamese artists, such as Mai Thu and Vu Cao Dam, showing alongside Chinese artists Pan Yuliang, Zao Wou-ki and Georgette Chen.[15] The search for original salon catalogues took us to a number of different libraries in Paris, including the Bibliotèque Nationale de France, the Kandinsky Library of the Centre Pompidou, and the Centre for Documentation at the Musée des Années 30 (Museum of the 1930s) in Boulogne-Billancourt.

Similarly to ENSBA records, Vietnamese artists comprised the majority of artists by country represented in the Paris salon exhibitions, with 42 out of the total 85 artists. However, Southeast Asian artists as a whole, spread across a wide variety of Salons. Of the 127 records of individual artists by salon, 33 records were from the Société des Artistes Français. The 1930s marked a peak when a number of Vietnamese artists began to submit works to this Salon, later joined by more artists from Singapore and Malaysia in the 1950s and early 1960s. For the independent and dissident salons, a continued participation by artists associated with Southeast Asia emerged in the 1930s, when Georgette Chen, Vũ Cao Đàm, Mai Trung Thứ and Lê Phổ began to participate in the exhibitions of Salon des Artistes Indépendents (Salon of Independent Artists). The Salon d’Automne was found to be one of the most popular salons for artists associated with Southeast Asia. Twenty artists associated with Southeast Asia showed their work there over 38-year period including Georgette Chen and Liu Kang. It was also a favorite among the Vietnamese émigré group of Vũ Cao Đàm, Mai Trung Thứ and Lê Phổ.

Despite the common assumption that affiliation with a certain type of Salon was an indicator of the artist’s stylistic and ideological orientation, what was particularly interesting was that artists associated with Southeast Asia often exhibited across variant salons, often simultaneously. For example, Georgette Chen exhibited six works spread across four salons: Salon d’Automne, Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Salon des Tuileries, and Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1936. This is possibly an indication that artists wished to expose their work as widely as possible, and were more concerned with having their work accepted and shown than with the cultural or ideological position of the individual salon. It is also, however, perhaps an indication of the changing role of salon exhibitions. As avant-garde art tended to be practised outside the salon system from that period on – including the breakaway and dissident salons – individual salons tended to be less strongly associated with particular styles and movements as they had been in the 19th century.

Miscellaneous Exhibitions and Resources

While ENSBA and the salons were our main areas of systematic research, we were also able to find traces of Southeast Asian artists’ activities in Paris in other places. This part of the research was necessarily less systematic and comprehensive, but did also yield some interesting results, including exhibition ephemera, press reviews and documentation, and surviving artworks. Some examples include the Documentation Centre at the Musée des Années 30, which contained dossiers on the large “World’s-Fair type” international exhibitions of 1931 and 1937, in which a number of Vietnamese artists participated. That Centre also contained individual artist dossiers for artists in Paris in the 1930s, including certain Asian artists. The Kandinsky Library at the Centre Pompidou held catalogues relating to the early years of the Paris Biennale (1959–1961): an exhibition described as “a place for encounters and experimentation among young artists,” distinct from the existing prestigious biennial exhibitions of Venice and Sao Paolo exhibitions which exhibited more established artists.[16] Through these catalogues, we discovered that Vietnam (in the form of the Republic of Vietnam or South Vietnam, as these exhibitions took place during the years of Vietnam’s division), Cambodia and the Philippines all participated officially in these years. In these biennales, artists exhibited in Paris as representatives of the newly-forming post-colonial nation states of Southeast Asia: some of the artists featured included Men Makoth, Sam Youen and Lay Bun Kim from Cambodia; Oscar Zalameda and Nena Saguil from the Philippines; and Nguyen Dinh Cuong and Ngy Cao Uyen from Vietnam.[17]

Tracing extant artworks in Paris was a challenge, and we often found results largely by chance. Based on our previous experience researching for the exhibition Reframing Modernism: Painting from Southeast Asia, Europe and Beyond, in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou, we discovered that some Southeast Asian artworks did enter into French public collections: for example, a painting by Georgette Chen that was displayed in that exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore in 2016.[18] Follow-up research in the state’s acquisition files in the National Archives also revealed a number of acquisitions of works by Vietnamese and Chinese artists by the state’s Fine Arts Administration.[19] Other artworks turned up more unexpectedly. The prints and drawings collection of the Bibliotèque Nationale de France, Richelieu site, contained some examples of print works by Vietnamese artists, including Lê Phổ [fig. 5].

Future Directions

Although information was uncovered about the general activities of a large number of artists, there were also areas of omission that future research could address. Importantly, by concentrating on publicly-available records like those for formal art schools and salons, this project was not always able to capture the activities of avant-garde artists who operated outside of these official circles. Nena Saguil, for example, despite her long period of residency in Paris, appears only once in our records: when she participated in the Second Paris Biennale. Saguil had studied at the private Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and had her work shown in the gallery of Raymond Creuze.[20] However, the types of records consulted for this project so far do not capture the activities of spaces like informal art studio schools or commercial galleries, as these are not as systematically available in public collections. For practical reasons, it was not possible to try to find such records in this initial research. Nonetheless, these kinds of places became increasingly important throughout the 20th century, and to obtain a full picture of Southeast Asian artists activities in Paris, as well as their connections to the avant-garde, it would be useful to be able to undertake research on these sites.

Since the records have been deposited with the National Gallery Singapore’s Rotunda Library and Archive, they have been accessed by researchers from the region and beyond. Lisa shared the research findings at art history conference and seminar in Shanghai and Tokyo to call for cross-regional examination.[21] Phoebe was also able to use research related to the activities of Vietnamese artists in Paris in the 1930s–40s in an in-depth article she published exploring the subject.[22] Curatorial discussion is also ongoing to take the research findings further to interrogate what Paris meant for artists in Southeast Asia and beyond, and how their experiences in Paris informed their artmaking in the period between the two world wars.

Notes

- For an interesting discussion on the volume of institutional structures that made Paris a “modern art centre”, see Fae Brauer, Rivals and Conspirators: The Paris Salons and the Modern Art Centre, (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), pp. 1-11.

- For Singapore, see Pont des Arts: Nanyang Artists in Paris, 1925-1970 (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1994); for Malaysia, see Yeo Hoe Koon, ed. Salon Pont des Arts (Kuala Lumpur: Galerie Petronas, 1997).

- For Salim, see Ajip Rosidi, Salim: un peintre indonésien à Paris [Salim: An Indonesian Painter in Paris], (Jakarta: PT Dunia Pustaka Jaya in collaboration with Cemara 6, 2003); for Nena Saguil, see Emmanuel Torres, Nena Saguil: Landscapes and Inscapes, from the Material World to the Spiritual (Quezon City: Ateneo Art Gallery, 2003).

- See Santiago Albano Pilar, Juan Luna: the Filipino as Painter (Manila: Eugenio López Foundation, 1980), pp. 70-198; Jane Chia, Georgette Chen (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1997).

- The research for this project was made possible by the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth, Singapore, and the Tote Board Group which comprises the Tote Board, Singapore Pools and Singapore Turf Club. The final research materials are available for consultation in the Library and Archives of National Gallery Singapore as: Phoebe Scott and Lisa Horikawa, “Artists from Southeast Asia in Paris, 1880–1960: Index of Art Schools and Exhibitions,” unpublished research report, Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017. Globibo Pte. Ltd. was commissioned to produce translations of selected French-language resources, also available for consultation in the Library and Archives of National Gallery Singapore.

- The National Archives have also compiled a guide on the different series of files available for ENSBA records, see Brigitte Labat-Poussin with the collaboration of Caroline Obert, Archives de l’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (AJ/52/1 à 1415), Paris: Centre Historique des Archives Nationales, 1998. We would also like to thank Mr Emmanuel Schwarz, conservateur du patrimoine at ENSBA for helping us to understand and navigate these records.

- The dossiers for individual students can be found in the series AJ/52/250-AJ/52/437. Lê Văn Miến’s dossier can be found under the code AJ/52/295.

- These files are under the codes AJ/52/553 and AJ/52/930-933, which contain the alphabetical and chronological registers of students in the ateliers, 19th century-1950s.

- These include the file codes AJ/52/470 which lists foreign students from 1878–1928 and AJ/52/958-964, which contain collectively details about the enrolment of foreign students from 1920–1966.

- Brauer, Rivals and Conspirators, p. 2.

- For a discussion on the persistence of the salons into the 20th century, see Natalie Adamson and Toby Norris, “Introduction,” in Academics, Pompiers and Official Artists: Defining Modern and Traditional in France, 1900–1960, ed. Natalie Adamson and Toby Norris, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), pp. 1-24.

- For a general background to the salons in the exhibition history of modernism, see Bruce Althuser, “Introduction,” Salon to Biennial: Exhibitions that Made Art History, vol. 1 1863–1959, ed. Phaidon and Bruce Althuser, (New York and London: Phaidon, 2008), pp. 11-19. For the formation of the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in particular, see Brauer, Rivals and Conspirators, pp. 107-137.

- Emmanuel Bréon, “Le Salon Essential,” in Dictionnaire des Indépendants: Repertoire des exposants et liste des oeuvres presentées, 1920–1950 [Dictionary of the Independants: Index of Exhibitors and List of Presented Works, 1920–1950], Vol. 1. A-E, ed. Pierre Sanchez (Dijon: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2008), pp. 13-6.

- These volumes, edited by Dominique Lobstein and Pierre Sanchez, were published by the Dijon-based publisher L’Échelle de Jacob over a period of many years (approximately 2000–2014), covering the main periods of activity for most Paris salons.

- Société du Salon d’Automne, Exposition de 1949 - Catalogue, (Paris: Durand, 1949).

- Raymond Cogniat, "Préface" to Première Biennale de Paris, exh. cat., (Paris: Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, 1959), VII.

- Records of the artists’ participation in the Paris Biennale are drawn from Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Première Biennale de Paris: manifestation biennale et internationale des jeunes artistes du 2 au 25 octobre 1959 [First Biennale of Paris: biennial and international show of young artists, 2-25 October, 1959], (Paris: Biennale de Paris, 1959) and Guido Marinelli, Les Biennales de Paris 1959-1961: Les Festivals d’Avant-Garde jusqu’à Comparaisons 1962 [The Biennales of Paris 1959–1961: The Festivals of the Avant-Garde up to the ‘Comparisons’ 1962], (London, Paris and Torino: M.A.O, 1962).

- On this work, see Reframing Modernism: Painting from Southeast Asia, Europe and Beyond, ed. Sarah Lee and Sara Siew, (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore), p. 50.

- The files relating to art acquisitions by the French state are held in the Archives Nationales, Pierrfitte-sur-Seine site, and are part of the F/21 “Beaux-Arts” series, specifically F/21/6721-6967, acquisitions and commissions in the years 1931–1960.

- Torres, Nena Saguil, 8, 11.

- The Second Conference on Chinese Modern Art History, 21-22 October 2018, Shanghai University; Seminaire: Les artistes asiatiques a Paris dans l’entre-deux-guerres, 15 September, Maison franco-japonaise, Tokyo. The latter’s abstract can be found in Bulletin de la societe franco-japonaise d’art et d’archeologie, no. 38, 2018: 54.

- Phoebe Scott, “Colonial or Cosmopolitan? Vietnamese Art in Paris in the 1930s-1940s,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, 3: 2 (October 2019): 187-240.