We Need to Talk: Race

Andrea, a member of the Gallery's experimental programme Kolektif, reflects on how and artists can contribute to discussions on race, inclusion and diversity.

I’m Andrea and I’m part of Kolektif 2021, the Gallery’s youth museum collective for 17 to 25 year olds.

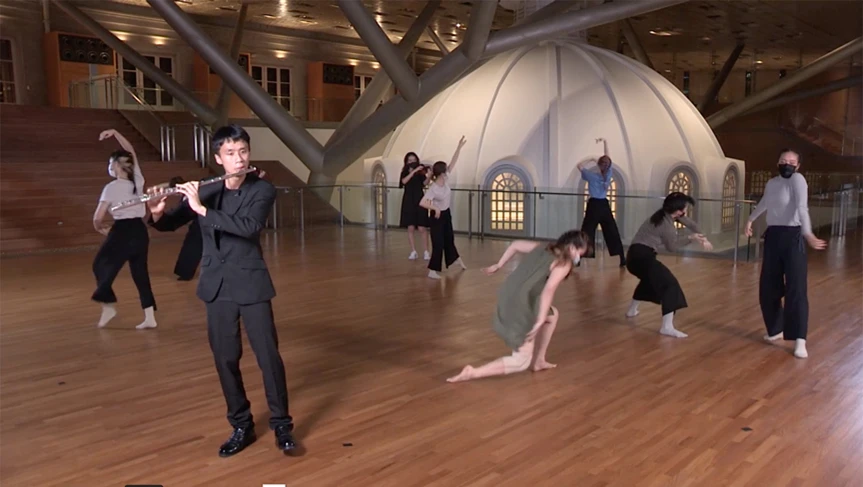

Kolektif is a 9-month programme that empowers youth volunteers to create and stage exciting youth museum experiences for other young people at the Gallery’s annual Light to Night Festival. Throughout our Kolektif journey, we get to go behind-the-scenes of the museum museum with learning sessions, kickstart special passion projects, uncover networking opportunities, and participate in art-making workshops. Importantly, the programme also cares about encouraging conversations on issues that matter to young people into the museum space.

One of those issues is that of race-relations in Singapore. In response to the numerous incidents of race-based discrimination in Singapore, our amazing Kolektif Coordinators pulled together a panel discussion featuring local minority race creatives entitled, “We Need To Talk: Race x the Arts.” The panel consisted of the talented Shaza Ishak, Kristian-Marc James Paul, Myle Yan Tay and Mysara Aljaru, all of whom generously shared their experiences of creating and staging works about race in Singapore.

Shaza is the managing director of Teater Ekamatra, an ethnic minority theatre company in Singapore that was established in 1988. Her wealth of knowledge in the theatre space is so inspirational to many young local arts practitioners. She is also very passionate about documenting ethnic-minority art—a task that is incredibly important.

Similarly, Kristian, Yan and Mysara, the team behind Brown is Haram, a performance-lecture on minority-race narratives, create a safe space for discussion through their work. Their collaboration has also contributed towards ensuring that conversations about minority race experiences are accurately portrayed and celebrated.

The Kolektif members had innumerable takeaways. The discussion covered the topics of censorship, accessibility (or the lack thereof) to minority-race art and the meaning and manifestations of allyship in Singapore. Our Kolektif members also asked powerful questions such as: How can minority-race artists work with formal and informal art practices to express their experiences of race-based stories? How can majority-race artists be supportive of art about the minority-race experience?

Each speaker shared insights that really resonated with me.

Shaza shared that she is always happy to lend a helping hand to local creatives. As a young individual in the arts scene who’s just starting out, this was really encouraging for me.

I’m sure many others would agree (especially those who were not born into families with an artistic background, or were even discouraged from pursuing their passion in the arts) that having a role model with a library of experience is essential. Reflecting on my own artistic journey thus far, there have been countless instances where I have benefitted from the perspectives of seasoned filmmakers. They’ve shown me how I should proceed forward with my work, and provided me with motivation to continue on my artistic journey. Connections with veterans can serve as an important resource when trying to manoeuvre the perils of censorship and managing the presentation of what some may deem as controversial material.

As Shaza mentioned, it’s important to continue pushing the boundaries of your creative work.

Kristian’s interests in exploring the intersectionality of race and gender relations really pushed us to rethink how we should be viewing our own identities, encouraging a well-rounded perspective.

As an Indian female, there are countless preconceived notions and stereotypes that others put on me. But when people get to know me, they realise that I’m much more complex than these reductive tropes. Not everything can or should be attributed to neat boxes and labels.

Kristian has been intentional and successful in ensuring that Brown is Haram was inclusive of his identities. His mindfulness about the need to showcase diversity even within our minority communities is admirable. It demonstrated the clear understanding that each individual journey is different from others, even if we all hold the same racial identity. It reminds us that communities are not homogenous and that we each hold a wealth of stories.

As Kristian mentioned, your power to connect with your audience lies in presenting your own truth.

Yan’s optimism in presenting the stories of individual truth, as well as the possibility of reconciling the varied responses of agreement and disagreement from audiences over the artistic representations of the minority experience, highlights the importance of authenticity in one’s work.

To Yan, it is important to make people laugh. His idea of using comedy to present heavy topics has allowed his audiences to be entertained while still engaging with the issues of race and racism. Cracking jokes and using laughter to present sensitive topics is a clever method that encourages accessibility and lowers the barrier of entry to discussions about minority experiences.

For him, it is important to make your audience smile through your work, even if you are working with difficult and potentially heavy topics. One of my local heroes is the comedian Kumar, who is another amazing example of what it means to present truths in an entertaining manner that at the same time, doesn’t invalidate the experiences of fellow minorities. Kumar’s work will always be the hallmark of what it means to shed light on race relations.

Last but certainly not least, Mysara shared that her work is not always meant to cater to the majority audience, reminding me that this is a point that is often overlooked. Sadly, there will always be a variety of reasons why it never will.

Not all work is meant for everyone, and no artist should ever feel the need to compromise on their creative vision for the sake of majority acceptance. Minority creatives and the stories they wish to share should especially not be watered down for the sake of mass understanding.

As creatives, we want to create work that is authentic to our ideas and that our respective communities can enjoy. We deserve to have the equal opportunity to be storytellers of our rich culture and heritage and receive due respect when presenting it.

As Mysara so powerfully put it, your work will not be for everyone, and that is OK.

From my perspective, one of the real drivers for the success of race-related work is that it is determined to tell a diverse range of stories. Institutions such as the Gallery play an important role in creating spaces for forward-thinking discussions surrounding race and racism. As such, the importance of inviting minority race artists and practitioners to tell different and unique stories is the key to the future.

The act of creating space has never been to vilify or create divisions between minority and majority race individuals. Instead, it helps to spark meaningful conversations about the inequality between them. The purpose of inviting diversity into any space is not to discard its current occupants, but to evolve and widen the area for more participation.

The landscape is meant to evolve, and it’s about time we unpack and rediscover the true meaning of inclusion and diversity.

As I've frequently said, it's not about crossing the finish line first, it’s about crossing the finish line together, and I remain hopeful that one day, this ideal will truly be achieved.