Singapore Stories: New Directions in Art for SG60 & 10th

The only SG60 signature programme dedicated to Singapore’s art history, this long-term showcase honours the diverse lives, practices, and perspectives of artists who have made, taught, shared, and lived art in Singapore.

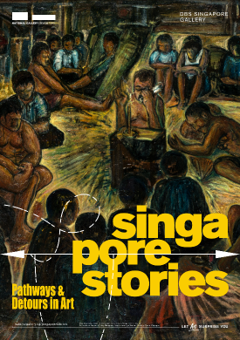

SINGAPORE, 10 July 2025 – Marking its 10th anniversary and Singapore’s 60th year of independence, National Gallery Singapore presents the full opening of Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art — the first major rehang of the DBS Singapore Gallery since its inception in 2015, and a bold rethinking of how Singapore’s art history is told. Expanded in scope and reimagined across newly configured spaces on the entire second floor of the Gallery’s City Hall Wing, the new exhibition will present a layered, artist-centred narrative of Singapore’s history through art. Featuring over 400 artworks and artefacts — from iconic masterpieces to rarely seen works from the National Collection — it spotlights artists' multi-faceted lives, practices, and perspectives to reveal how artistic life in Singapore has always been more expansive, porous, and deeply human than previously recognised in past exhibitions of art from Singapore.

“This exhibition speaks to who we are — not just as a cultural institution from Singapore, but as a society,” says Dr Eugene Tan, Chief Executive Officer and Director of National Gallery Singapore. “By presenting a more inclusive, nuanced, and multi-perspectival account of Singapore’s art, Singapore Stories affirms that art is not merely a mirror of progress, but a record of detours, negotiations, and deeply personal choices. It offers all visitors a richer way of understanding where we have been — and where we might be headed. In doing so, we continue to deepen public engagement with the nation’s art and broaden representation, ensuring that more Singaporeans can see themselves in our shared stories.”

Completing the journey through Singapore’s art history

The exhibition spans from the 19th century to the present day and embraces a thematic approach to art history while retaining a broad chronological arc. The first part, which opened in December 2024, traces the early expressions of artistic community and identity in Singapore, framed through pivotal historical moments up to the 1960s, such as colonialism and independence. Building on this foundation, the newly unveiled sections extend this narrative into the post-independence period, spotlighting the impact of rapid urban transformation, evolving cultural policies, and efforts at community-building. As artists responded to these shifts, they expanded their visual language by experimenting with different mediums, materials, and art forms, including installation, performance, and video.

During Singapore’s transformative decades in the 1950s and 1960s, artists evolved their art practices to create works that responded to the world around them through modern expressions. Visitors can witness how artists made sense of the changes around them in the sections Expanding Horizons and Presence. Some artists like Cheong Soo Pieng, Khoo Sui Hoe, and Vincent M. Hoisington turned to semi-abstract forms, reinterpreting diverse cultural sources and the world around them to develop distinct artistic vocabularies. At the same time, portraiture and still life — which were core to the teaching at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts — remained central to artists like Georgette Chen, Ng Eng Teng, and Lim Mu Hue as a vital mode of expression.

Through sections Liberating Form and Colour and Vectors of the New, viewers will learn how artists, from Ho Ho Ying to Kim Lim and Eng Tow, advanced new ideas and perspectives on art in tandem with the international art world. They embraced the modernist ethos of ‘newness’, and experimented with form, colour, and everyday materials to expand the possibilities of their chosen mediums. Other artists like Kwan Shan Mei, Shamsuddin H. Akib, and Choy Weng Yang also ventured into other domains like graphic design, illustration, and cartoons.

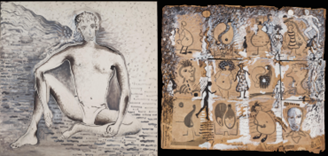

Body, Self and Other highlights the persistence of the human figure in art even as alternative art forms were on the rise in the 1990s. The section features works by Solamalay Namasivayam, who devoted his practice to the study and interpretation of the human figure, as well as artists like Amanda Heng, Ho Soon Yeen, and Susie Wong, who explored issues of identity, representation, and gender through the body.

As Singapore’s economy boomed in the 1980s, so did its cultural scene. Singapore Stories spotlights the independent ground-up initiatives and community-based practices in Coming Together for Art and A Space of their Own, introducing visitors to artists, art spaces, and arts collectives behind these events, such as Gilles Massot, The Artists Village and Plastique Kinetic Worms.

In the final section, Navigating the Interdisciplinary, the exhibition celebrates the growing potential of Singapore's cultural landscape with greater exposure to literature and theatre in school and expansion of governmental infrastructure for the arts. The exhibition also features contemporary commissions that bridge the past and present, reviving earlier artistic concerns and reimagining them through today’s lens.

When enjoyed in full, Singapore Stories illuminates the many pathways, detours, and networks through which Singapore’s art has taken shape over the past 200 years. It offers a more inclusive and textured representation of homegrown voices, from celebrated pioneers to lesser-known figures, including cross-disciplinary practitioners, artist-educators, and others historically underrepresented in art history.

“As a founding partner of National Gallery Singapore, we are proud to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the DBS Singapore Gallery and the launch of Singapore Stories. Singapore Stories captures the ever-evolving nature of our nation’s art history and reflects the rich cultural fabric that defines Singapore,” says Ms. Karen Ngui, Head, DBS Foundation and DBS Group Strategic Marketing and Communications. “DBS has been an integral part of Singapore’s story since 1968, when it was founded to drive the nation’s industrialisation — this makes the launch of Singapore Stories even more meaningful, as we commemorate milestones such as SG60 this year. Through exhibitions like these, we hope the DBS Singapore Gallery will spark a deeper sense of national pride and inspire more to appreciate Singapore’s artistic heritage.”

New spaces, new possibilities

With new project spaces, Singapore Stories opens up fresh curatorial possibilities and provides more dynamic ways for audiences to engage with Singapore’s art. Among the additions is Dalam Singapore, a new series of small exhibitions in the annexe of DBS Singapore Gallery 3, which is designed to foster deeper engagement with Singapore’s art through innovative research, insightful curation, and engaging programming. Exhibitions at Dalam Singapore will be periodically refreshed, offering focused explorations of specific artists or themes that give deeper insights into lesser-known figures and stories from Singapore’s art history. Its inaugural presentation, Tchang Ju Chi: Tireless Camel, marks the first exhibition in over five decades to showcase the rare works of this pioneering artist, offering a renewed exploration of his significance and contributions, and reintroduces him to audiences today.

The Gallery has also taken this opportunity to imagine more future-forward ways for visitors to experience the artworks, exhibitions, and museum. As part of Singapore Stories, the Gallery introduces a new art commission currently in development with artist Amanda Heng. From August, Let’s Chat Further (2025) will be a series of livestreamed performances that see Heng hold virtual conversations with visitors via holographic technology. Over time, Let’s Chat Further (2025) evolves into an experience where visitors can engage in conversations with a fully AI-based persona based on the artist, Retired Singirl (2025-2030).

“These commissions connect the questions of past generations of artists to the present, reminding us that our art history is alive, and deeply relevant to an evolving society,” says Dr. Seng Yu Jin, Project Director of Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art. “With Amanda’s new works, we are exploring different ways for the public to experience and participate in art. It invites visitors to engage directly with a live artwork powered by advanced technology — not just as observers but as collaborators. In doing so, we hope to open up deeper conversations about what art means to us today: What makes Singapore's art history ours? What roles do artists play in reflecting and shaping the world around us? At its core, it is about creating a space where our art history can continue to grow, shaped by new perspectives, shared experiences, and the voices of the communities it speaks to.”

Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art fully opens on 18 July 2025. A General Admission pass is required, and entry is free for Singaporeans and Permanent Residents. For more information, please refer to the annexes or visit https://www.nationalgallery.sg/SingaporeStories. Media assets are available through this link.

● Annex A: Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art Sections and Key Artworks

● Annex B: Dalam Singapore: Tchang Ju Chi: Tireless Camel Sections and Key Artworks

● Annex C: Exhibition Programmes for Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art

● Annex D: List of artists in Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art

– END –

Annex A: Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art Sections and Key Artworks

Expanding Horizons

Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, rapid socioeconomic and technological changes transformed the city-state and catalysed a wave of artistic innovation. As the nation modernised, fine art education and commercial design flourished, creating fertile ground for artists to reflect and respond to the shifting landscape. There was a shared urgency to develop new modes of expression — art that could engage with the aspirations, complexities, and contradictions of a newly independent and rapidly evolving society. This period saw the rise of a generation of artists coming into national prominence, whose pursuit of the “new” in art mirrored Singapore’s broader ambitions for progress.

Widely associated with modernity, abstraction became a key mode of image-making. Artists affiliated with institutions like the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) and self-taught practitioners contributed to the rise of abstraction in Singapore. While engaging in international conversations around abstract art, they also drew from a rich array of sources — Nanyang pictorial schemas, local and regional idioms, and diverse cultural influences — to develop distinct artistic vocabularies unique to their contexts.

This spirit of openness and exploration defined the era. Many artists moved fluidly between figuration and abstraction, expanding artistic boundaries through new techniques and forms. Vincent M. Hoisington’s Civilization (c. 1970s) exemplifies this shift, revealing the immediacy and flatness characteristic of action painting while retaining a compositional structure grounded in representational forms. Figures appear to emerge subtly from the negative space, suggesting an interplay between abstraction and figuration that reflects the broader experimentation of the time.

Presence

As society continued to evolve through the 1960s, portraiture and still life painting remained foundational for modern artists, providing a vital mode of expression through which they grappled with how best to represent the human figure and, in doing so, reflect on the evolving identities of their time. Figuration took on innovative representational and compositional approaches, primarily through self-portraits and intimate depictions of fellow artists and friends. These works demonstrated new aesthetic sensibilities while capturing the presence of their subjects and the nuanced relationships between artist and sitter, revealing both personal and broader social realities.

At NAFA, figurative art — rooted in direct representation of the physical world and honed through repeated observational drawing sessions — was central to artistic training. NAFA became a key institution for postwar art education in Singapore, nurturing generations of artists under influential artist-teachers such as Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, and Chen Chong Swee. Artists like Georgette Chen, who studied abroad and were steeped in figure drawing as part of their foundational training, returned to Singapore to teach and exhibit, emphasising discipline, observation, and the cultivation of individual artistic voices. These values are embodied in works such as Rohani (1963), a portrait of Chen’s student Rohani Ismail, painted during her teaching years at NAFA.

Liberating Form and Colour

The artistic and cultural exchanges of the 1960s further gave rise to new ideas and perspectives in Singapore, developing in conversation with international art movements and resulting in a proliferation of stylistic approaches. Many young artists broadened their outlooks through travel, overseas study, and exposure to global art publications. These encounters introduced them to multiple modernisms and prompted reflection on their roles within both local and international contexts. The Modern Art Society (now known as Modern Art Society Singapore), for instance, championed a universal formalist language that could reflect local and regional sensibilities while engaging with global artistic discourses and signalling a modern identity.

Amid these intersecting national, regional, and international influences, fertile ground emerged for experimentation and creative freedom. Artists pursued new ways of seeing and making, often moving away from literal representation to explore formal elements — colour, form, texture, and space — as tools to evoke harmony, emotion, spirituality, and the cosmic. Others pushed the boundaries of traditional art forms such as batik, negotiating the tension between craft traditions and modernist abstraction. In Structure I (1973), Yusman Aman exemplifies this spirit of innovation, integrating batik techniques with abstract visual language to express a modern sensibility rooted in a shifting cultural landscape. Similar movement, emotion, and rhythm qualities are present in Jaafar Latiff’s unsigned and undated composition, [Title unknown] (c. 1976), where vivid hues and organic forms converge in a dynamic form of artistic expression.

Vectors of the New

As modern art evolved in the 1970s, artists increasingly turned their attention to art's physical form and material qualities. Seeking to expand perceptions and introduce new ideas and experiences, they experimented with emerging industrial materials and technologies such as plastic, steel, fibreglass, and textiles. These explorations redefined the possibilities of painting and sculpture, where elements like light, colour, and rhythm became central to transforming how art was experienced. Eng Tow’s Grey Shadows (c. 1970s) captures this shift: a subtle and intricate study of rhythm and light, the work features a square ticking cloth meticulously stitched and pleated into nine different patterns, creating a mesmerising grid that blurs the boundaries between art and craft while reimagining textiles as a rich, expansive medium.

Alongside individual works, this section presents artist-focused clusters that establish visual and material dialogues between artworks, triangulating connections between artists, and drawing out shared sensibilities. In Growth (1985), Han Sai Por sculpts marble — a material associated with strength and permanence — into life-like and fluid shapes. This exploration of form and material resonates with Interplay Between Traditions and Contemporary Forms: #2 Jawi Arabic Scripts (2002) by Iskandar Jalil, where flowing, rhythmic repetitions of Jawi calligraphy ripple across the surface of ceramic, appealing as patterns that merge a Malay consciousness with creative new ideas. Suriani Suratman, a former student of Jalil, continues this exploration of form and symbolism in Third Shift 1 (2017), where three interconnected gasing (spinning tops) represent the delicate balance of the multiple roles women navigate across work, family, and community.

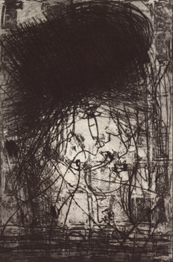

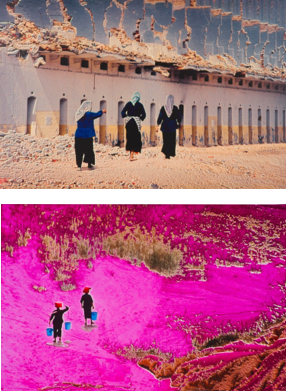

A broader spirit of innovation also characterised the practices of artists associated with Alpha Gallery, a pioneering artist-run space, and those who returned from overseas to teach at LASALLE College of the Arts. The influence of these returning artists played a significant role in shifting the focus of art education towards applied arts, deepening the connection between art and industry. During this period, artists explored new fields, including commercial and graphic design, while making significant strides in photography, printmaking, ink, sculpture, and ceramics. Chng Seok Tin, a key figure in developing printmaking in Singapore, personifies this spirit of innovation. In her work Self-Portrait (1989), a dense tangle of lines envelops a simply drawn figure, creating an energetic tension that conveys both struggle and resilience. Similarly, in works like Three Workers (1965) and Two Workers (1968), Tan Lip Seng employed a technique known as colour-derivation montage — the result of ongoing experimentation — to document Singapore’s changing physical landscape and the human experience within it. Together, these works reflect the modernist ethos of “newness,” expanding the possibilities of the artists' chosen mediums to engage with contemporary contexts and marking a significant step forward in developing Singapore’s modern art scene.

Body, Self and Other

Amid the rise of alternative art forms, artists continued to create images of the human body as a personal and profound act. For many, the human figure remained a vital aesthetic focus that shaped their development as artists. For example, the informal collective Group 90 was dedicated to studying and interpreting the human body, staging exhibitions and holding closed-door life drawing sessions at LASALLE College of the Arts.

Despite lingering cultural anxieties around nudity in art, artists continued to engage with the body as a way to probe questions of representation, identity, and the act of viewing itself. Some extended this exploration through performance, using their bodies to question shifting social and cultural norms. This section brings together powerful micro-narratives — feminist concerns with the body, acts of self-representation, and collective practices like life drawing. Here, the body is not simply presented as “the nude,” but as a dynamic site through which artists negotiated identity, power, and modernity.

Coming Together for Art

The 1980s ushered in a new sense of dynamism in Singapore’s cultural scene, as artists sought to deepen the relationship between art and civic society. Building on initiatives like the Singapore Arts Festival and the Festival of Arts Fringe, artists began to organise their multidisciplinary events that intervened in public spaces and fostered peer solidarities, laying the groundwork for forming artist collectives.

One seminal initiative was the Yin Yang Festival, launched in 1987 by French-born Singaporean artist Gilles Massot, who was inspired by the temporal format of the Festival of Arts Fringe. The festival featured multidisciplinary programming that spanned visual art, photography, music, dance, drama, poetry, and fashion. On display is Massot’s Yin-Yang One and Many (1987), a double-sided portrait and collage that reflects his view of life as an exchange between self and society.

The festival brought together key art practitioners and thinkers to workshop with students across Singapore, fostering dialogue on artmaking and space. Among the student participants was Vincent Leow, who later emerged as a significant figure in the local arts scene. His early work, Rooster (1989), created after graduating from LASALLE College of the Arts, is featured in this section. Leow would later participate in the Art Commandos, a month-long event that took performance art to the streets of Singapore, and also involved Ahmad Abu Bakar and Khairul Anwar Salleh. Their artistic journeys reflect those of many others shaped by the formative, informal networks fostered through such initiatives — students who would become practising artists and core members of collectives central to Singapore’s contemporary art history. Together, they became a cohesive voice engaging with their time's social and cultural questions. This spirit of experimentation is evident in Ahmad Abu Bakar’s two Untitled works from 1995, which explore geometric and abstract forms, reflecting his ongoing engagement with themes of movement and dance — disciplines that came to influence him during the Art Commandos workshops.

Notable among these collectives was The Artists Village. Co-founded by Tang Da Wu, the collective turned to the rural as a site for reflection, offering a counterpoint to Singapore’s burgeoning urbanisation. Tang’s work Just in Case (1991) exemplifies his layered approach to meaning: a sealed wooden crate marked “from Burma to Singapore” invites viewers to peer through a peephole. When lit by a torch, the interior reveals the word “JUST” — a clever play on “justice” that also references the idea of something being “encased”. The work prompts viewers to reflect on Myanmar's political and social conditions, seen — quite literally — from a distance in Singapore.

A Space of their Own

As Singapore’s rural areas underwent redevelopment in the 1990s, artists began seeking new, alternative platforms to present contemporary art and experimental practices. This period saw the rise of independent, artist-run spaces. Often housed in unconventional locations, these spaces challenged conventional ideas of where, when, and how art could be experienced. These platforms allowed artists to experiment and engage more directly with local publics and the broader arts community — locally and internationally — while sparking dialogue around pressing social issues.

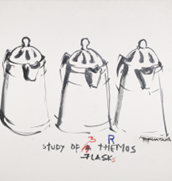

The timely concerns are reflected in works such as Chua Chye Teck’s My Ah Kong’s Big House (1999). Comprising twelve wooden towers of varying heights painted in industrial white, the installation is arranged in a dense cluster, offering a subtle commentary on the homogenisation of the urban landscape and how built environments shape societal ideals and prioritise production efficiency. Khairul Anwar Salleh’s A Study of 3 Thermos Flasks (1990) captures the period's often radical energy. Stylistically distinct from his other works, it features nonchalant brushstrokes and visible corrections, conveying a playful tone that pushes against the prevailing seriousness of contemporary art at the time, while also standing as a personal and irreverent response to the global sociopolitical forces shaping Singapore’s cultural landscape.

Navigating the Interdisciplinary

The mid-1990s marked a pivotal shift in Singapore’s cultural landscape, driven by policy changes and institutional reforms. Following the 1989 Advisory Council on Culture and the Arts’ recommendations, the government invested heavily in arts infrastructure. This included introducing subjects like English Literature and Theatre Studies into school curricula, broadening access to the arts, and shaping a generation of artists attuned to working across disciplines.

This ecosystem allowed interdisciplinary practice to flourish. As part of their artistic language, many artists began moving fluidly between forms, merging theatre, moving image, and installation. Public institutions became both sources of support and systems to navigate, as artists continued making meaning within and around them. The opening of the Esplanade in 2002 expanded the space for experimentation, offering a dedicated platform for interdisciplinary theatre practices that fostered new conversations, supported cross-disciplinary collaborations, and connected Singapore-based artists with the international arts community.

Annex B: Dalam Singapore: Tchang Ju Chi: Tireless Camel Sections and Key Artworks

Tchang Ju Chi (张汝器) (b. 1904, China; d. 1942, Singapore) was a prominent and pioneering artist, active in Singapore from 1927 to 1942. Trained in Western painting at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts and later spending time in France, a friend persuaded him to stay in Singapore — a move that ultimately made the city his home and transformed its nascent arts scene.

Tchang once likened artists to camels: unyielding and trudging tirelessly with slow but sure steps, driven by a sense of mission. This metaphor speaks to his conviction and courage to forge new paths forward. He stood at the vanguard of a blossoming visual arts scene in Singapore, where exhibitions were held regularly and art discourse began to take root.

As one of the earliest artists to integrate local subject matter into his work, Tchang played a pivotal role in the emergence and development of the 'Nanyang Art' movement in Singapore. His work influenced many of his contemporaries and was critically acclaimed by many of his illustrious contemporaries, including Xu Beihong, Chen Chong Swee and Liu Kang. Yet, despite his contributions, his name and work have not fully percolated into public consciousness. This exhibition brings together — for the first time in over 50 years — a rare collection of artworks, reproduced cartoons and archival materials, providing a revelation of the artist’s contributions and legacy.

Leading the Charge

Tchang’s legacy began to take root in the late 1920s, when he emerged as a central figure in Singapore’s budding arts community. Believing art could awaken the masses, he rallied like-minded peers to form a society grounded in shared ideals. At age 32, he co-founded the Society of Chinese Artists (SOCA) and served as its first president, aiming to promote art and foster regional exchange. Under his leadership, SOCA became a vital platform for artistic activity, organising regular sketching sessions, artist gatherings, and annual exhibitions. Between 1936 and 1941, over 60 artists contributed more than 900 works to its exhibitions, helping to cultivate a vibrant cultural environment in Singapore.

Throughout this period, Tchang led by example, exhibiting more than 70 works, including Self-Portrait (1939). Beyond his artistic contributions, he played a key role in fundraising for war relief, served on selection committees, and hosted visiting artists such as Xu Beihong, affirming his stature as a central and respected figure in Singapore’s Chinese artist community.

Painting Local Colours

The next section of the exhibition explores the connections between Tchang Ju Chi’s works and contemporaneous literary discourse on local identity. Between 1927 and 1930, a new literary movement emerged in newspaper supplements such as Huang Dao (荒岛) and Yeh Lin (椰林), where editors called for writers to root their storytelling in the world around them, drawing on local scenery and motifs such as coconut trees, rubber plantations and tropical weather to reflect lived experiences and local culture.

Tchang was one of the earliest artists to translate this literary ethos into visual form. He depicted scenes of everyday life — multicultural communities, coconut groves, attap houses, and tropical fruits. His painting [Not titled] (Still Life) (c. 1930s), which features mangoes, rambutans, and mangosteens, exemplifies his pioneering effort to centre local subjects in his art. This approach profoundly influenced a generation of SOCA artists, with many following his lead in portraying local realities.

Cartooning Life

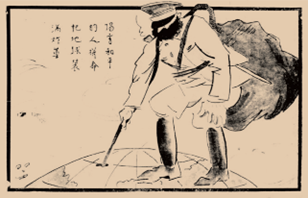

This commitment to depicting everyday life also defined Tchang’s work as a prolific cartoonist and editor. From the 1920s to 1942, he harnessed cartoons as a powerful tool for socio-political commentary, addressing issues such as the civil war in China, the brutality of the Japanese military, and the challenges faced by life in Singapore, including mass hunger, youth struggles, and immigrant apathy.

A striking example of this is 倡导和平的人拼命把地球装满炸弹 (Advocates for peace are filling the Earth with bombs), published in Xing Guang, Sin Chew Jit Poh (星洲日报) (1929), which reflected Tchang’s unwavering belief in the power of art to engage with the pressing concerns of his time.

Annex C: Exhibition Programmes for Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art

| Programmes | |

|---|---|

Title: Pathways & Detours: An Afternoon of Conversations on Singapore's Art Stories

Date, Time & Location: Sun 31 Aug | 2pm - 5.30pm | National Gallery Singapore, City Hall Wing, Level 3, City Hall Chamber

Price: S$5, registration required | Whose story is this? Where is home? What is new? Who is looking? What is art for?

We ask these questions because we never had just one answer.

Presented alongside the newly refreshed DBS Singapore Gallery exhibition Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art, this series of conversations explores the many threads that weave through Singapore’s art histories. It traces our stories – some underappreciated, some fragmentary, others complex and even contradictory – and responds to them with curiosity and care.

Featuring a multitude of voices, this programme opens up a space – not just for facts, but for feeling; not just for history, but for re-encounters. |

Annex D: List of artists in Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art

Abdul Ghani Hamid | Chua Mia Tee | Khairul Anwar Salleh |

Adolphe Willette | Chua Soo Bin | Khoo Sui Hoe |

Ahmad Abu Bakar | Dominique Hui | Kim Lim |

Amanda Heng | Dora Gordine | Koeh Sia Yong |

Annaratnam Gunaratnam | Edgar Ainsworth | Kwan Shan Mei |

Anthony Poon | Elsie Yu | Kwei Chin Pen |

Arthur Yap | Eng Tow | KYTV |

Aw Eng Kwang | G.R. Lambert & Co | Lai Foong Moi |

Aw Tee Hong | Gao Junbai | Lee Boon Ngan |

Baet Yeok Kuan | Georgette Chen | Lee Boon Wang |

Benjamin Phuah | Gilles Massot | Lee Cheng Yong |

Carl Gibson-Hill | Goh Beng Kwan | Lee Lim |

Chen Cheng Mei | Goh Ee Choo | Lee Man Fong |

Chen Chong Swee | Han Sai Por | Lee Sik Khoon |

Chen Kezhan Henri | Hazel McIntosh | Lee Soo Chee |

Chen Kunyi | Ho Ho Ying | Lee Sow Lim |

Chen Wen Hsi | Ho Kah Leong | Lee Wen |

Cheo Chai Hiang | Ho Soon Yeen | Lim Cheng Hoe |

Cheong Soo Pieng | Ho Tzu Nyen | Lim Chu Suan |

Chern Yet Siew | Hong Sek Chern | Lim Hak Tai |

Chia Wai Hon | Iskandar Jalil | Lim Kwong Ling |

Chng Seok Tin | Jaafar Latiff | Lim Leong Seng |

Chong Fah Cheong | Jessie Lim | Lim Mu Hue |

Chong Pai Mu | Jimmy Ong | Lim Nang Seng |

Choy Weng Yang | John Turnbull Thomson | Lim Swee Choon |

Chrisilda Cherian | Juliana Yasin | Lim Tze Peng |

Chua Chye Teck | Karl Duldig | Lim Yew Kuan |

Chua Ek Kay | KF Wong | Lin Hsin Hsin |

Liu Kang | Seah Kim Joo | Tchang Ju Chi |

Loo Foh Sang | Shamsuddin H. Akib | Teh Tien Chong |

Low Kway Song | Sharifah Fatimah Zubir | Teo Eng Seng |

Lu Guo Xiang | Shui Tit Sing | Thomas Yeo |

Mak Kum Siew | Soo Pun Ting | Tow Theow Huang |

Marco Hsu | Sun Yee | Vincent M. Hoisington |

Marianne James | Suriani Suratman | Vincent Leow |

Marianne North | Susie Wong | Wee Beng Chong |

McNally Joseph | Suzann Victor | Wee Kong Chai |

Ming Wong | Tan Lip Seng | Wong Jai Ling |

Mohamed Salehuddin | Tan Oe Pang | Wong Keen |

Mohd Ali Idris | Tan Ping Chiang | Wong Shih Yaw |

Natasha Wei | Tan Swie Hian | Xu Beihong |

Ng Eng Teng | Tan Tee Chie | Yan Fook Luen |

Oh Chai Hoo | Tan Teng Kee | Yazaki Chiyoji |

P. Ramlee | Tan Teo Kwang | Yeh Chi Wei |

Richard Walker | Tan Yee Hong | Yeo Hoe Koon |

Rong Yu'an | Tan Yueh Goh | Yip Cheong Fun |

Rudolfo Nolli | Tang Da Wu | Yong Mun Sen |

S Mahdar | Tang Mun Kit | Yu Tao |

S. Chandrasekaran | Tay Bak Koi | Yusman Aman |

S. Mohdir | Tay Boon Pin | Yvonne Lee |

S. Namasivayam | Tay Chee Toh | Zainudin Samsuri |

Salleh Japar | Tay Kok Wee | Zulharli Adnan |

Sarkasi Said | Tzee |

|