Art For Us - Burmese edition

“The seemingly uncomfortable and uninviting colonial interiors of the Gallery actually held the comforting, familiar artworks of Myanmar.” Hear from some of the participants of the Burmese edition of Art For Us, and how the programme created a welcoming space at the Gallery for its participants to connect with others and to destress.

Stern warnings, written in Burmese, can be found scattered throughout the Civic District in Singapore. Many of them read “စုရုံး/နားနေခြင်းခွင့်မပြု,” which translates to: “Do not gather/rest here.” It is only here in City Hall that one can find Burmese-language signboards in Singapore㇐but, disappointingly, they do not exist for the sake of inclusivity.

The Civic District, home to Singapore’s migrant Burmese community, is also home to National Gallery Singapore. On 18 July 2021, I made my way to the Gallery, alongside other Burmese participants, to attend Art For Us. Walking towards the impressive building of the Gallery, some of us felt intimidated, others excited.

Art For Us was a new Gallery outreach programme designed to support communities in need. This edition was organised to support the Burmese diasporic community in Singapore during trying times as they grapple with political instability in Myanmar and a raging global pandemic, aiming to bring emotional relief and encourage social connection through art. Conducted in the Burmese language by Burmese artist-facilitator Nyan Soe, the programme welcomed Burmese participants from diverse backgrounds, including tertiary students, working professionals, and domestic workers.

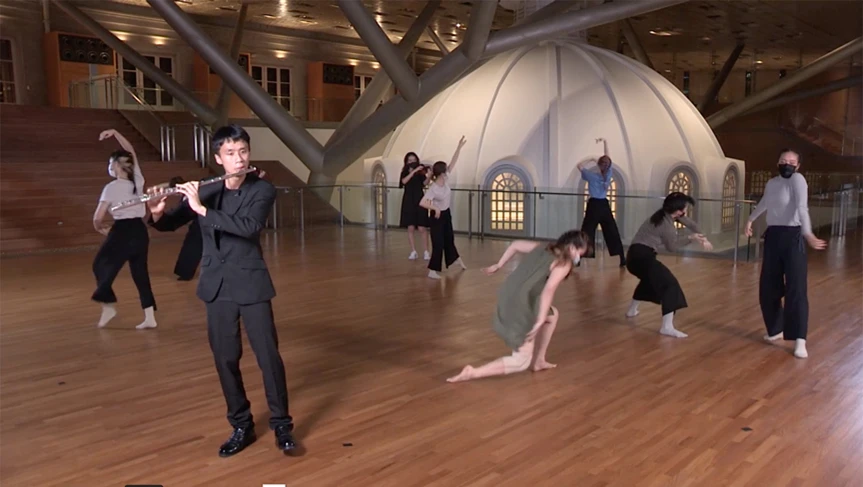

The three-hour programme comprised two parts: an artwork tour and a tote bag printing workshop.

During the tour, we visited and learnt about three artworks from our native land: a parabaik from the 1880s, Royal Family Portrait with Mustached Minister (1918) by Saya Aye, and Age of Full Bloom (1979) by San Minn. Spanning a range of time periods and artistic mediums, the three artworks presented participants with glimpses into different scenes from Myanmar across history.

One artwork stood out to me. Age of Full Bloom reflected the tense sociopolitical situation in Myanmar in the 1970s. Artist San Minn was imprisoned from 1975 to 1978 for his involvement in the anti-government demonstration of 1974, and created this painting soon after his release. It was regarded to be subversive as it criticised the state regime, and the work was taken by the censorship board when it was exhibited at the 2nd Gangaw Village Art Exhibition.

With Myanmar’s current political instability, Age of Full Bloom garnered significant interest and resonance from the audience as it reflected our emotions. “It just felt right; the time... the situation... the sentiments,” a participant shared.

One of the many things that participants appreciated about the art tour was that it was conducted in our home language, Burmese. Language plays a big role in making art accessible to different communities, and it is regrettable that language is often a high barrier to visiting and enjoying museums. Despite most participants having lived in Singapore for many years, this was the first visit to the Gallery for many of them, despite it housing the largest public collection of Southeast Asian Art in the world.

After the tour, we proceeded to the second part of the programme—a hands-on tote bag printing workshop!

The participants watched earnestly as Nyan Soe demonstrated the process of silkscreen printing a unique design, that the participants would create, on a canvas tote bag. The room was filled with excited chatter as participants sought his advice on their pencil sketches and applying their choice of paint to the bags. Many participants came up with designs that told important stories about the Spring Revolution happening back home.

Htet Myet Min Tun, a participant, drew the independence monument—a white towering obelisk symbolising freedom—located right in the centre of Yangon. It reminded him of the hustle and bustle of the city and its vibrant days of the past. “My aspirations and optimism for the path forward were reaffirmed no matter how dim the current situation is,” he shared.

Making tote bags provided us with an outlet to release the compounded stress that so many in our community are feeling. Burmese living overseas are feeling frustrated, as there are limits to what we can do to help the situation back home. Inundated by unceasing news updates of what is happening in Myanmar, this was a much-needed mental health break that allowed us to remove ourselves from the harsh reality back home, even if it was just for an afternoon.

Nyan Soe explains that the creative process allows us to spend meaningful quality time with ourselves and focus on the present: “The moment something appears in the making, we surprise ourselves with what we can achieve. This kind of excitement is a joyful moment in the making that I hope to deliver in these difficult times.”

As we waited for the paint on the tote bags to dry, I had the opportunity to chat with some of the participants. It allowed me to reflect on the different impacts that this programme had on participants from diverse backgrounds.

For the younger participants who grew up here, many of whom are still students, they had already assimilated into Singapore society. However, they often find themselves stuck in the liminal space between being Burmese and Singaporean. The art tour was an opportunity to learn more about their roots and culture. While the parabaik and the histories of Burmese royal families were foreign to many of them, they enjoyed discovering more about this history that they usually had limited access to.

Compared to the younger, second-generation participants, Burmese migrants who came here to work as adults have vastly different lived experiences. Society is often unwelcoming towards foreigners seeking employment here. This made the programme even more special to them, because of how inclusive it was and how it accommodated their needs and situations. Previously, many had shied away from the likes of the Gallery as they felt it was curated and reserved for the upper echelons of society. Unwelcoming attitudes from their past experiences might have caused them to believe that they do not belong in this space, despite the Gallery being a public museum that welcomes all.

Regardless of our backgrounds, we all found solace in spending time together with our community during these difficult times. Even among strangers, there is strength in solidarity and physical togetherness, especially in these times of the pandemic.

Art For Us, executed with cultural sensitivity and thoughtfulness, gently oriented participants to the Gallery and opened a space for community and emotional wellness through visual art. The seemingly uncomfortable and uninviting colonial interiors of the Gallery actually held the comforting, familiar artworks of Myanmar. Perhaps the Gallery is not so intimidating after all.