The Moon is Wet: Threading Desire Lines Across History

Charmaine Poh unpacks her new video installation, The Moon is Wet (潮间隐月), which centres around three migratory characters: the Chinese sea goddess Mazu, a Majie and an Indonesian domestic worker, Monic. Though they speak different languages, the characters form a spectral kinship that transcends geographical and biological chasms, providing an alternative foundation to the forefather historicity in Singapore.

In the third scene of my new moving-image work, a three-channel video installation titled The Moon is Wet (潮间隐月), a masked figure walks barefoot along the coast. The figure bends down to caress a cuttlefish bone, a jade bangle visible on the wrist. Viewers may recognise the figure, dressed in samfu and with hair tied in a bun, as a Majie (妈姐), part of a group of women who migrated from Guangdong in the early to mid-20th century to Hong Kong and British Malaya to work primarily as domestic workers.

In China, the Majie are also known as zhi shu nü (自梳女), which means "self-combed women," because of their lifelong vow of celibacy through the sor hei, a ritual in which they comb their hair up in a symbolic gesture, similar to one made during a wedding ceremony. During the decline of the silk industry, the path of a Majie was an acceptable alternative to marriage, one that allowed women to gain financial independence and move out of their hometowns.

In Singapore, they are characterised mainly by their role in the nation-building years as self-sacrificial labourers—often grouped together with samsui women—and less by their own intimate desires, an ambivalent distance typical of large swathes of women’s history studies throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Yet the figure of the Majie did not emerge out of nowhere; there had long been a culture of marriage resistance in Guangdong, one that had implications even for their afterlife.

While making one of my first photography works in 2016, I found several Majie living in one-room rental flats in Singapore’s Chinatown. These women were already reaching 90 years old; most, if not all, have since passed. Documenting them and their material environments was a race against time to gather any contemporary evidence of their existence in Singapore, not as folklore but as a concrete reality.

Almost a decade later, this figure of a Majie in The Moon is Wet was an entry to unspooling the thread further, making room for desires that have always existed in history.

I turned to Ann Stoler’s approach of reading “along the archival grain” as I opened pathways of knowledge, both formal and informal, that recognised the variability of histories solidified by society. Stoler emphasised reading an archive “for its regularities, for its logic of recall, for its densities and distributions, for its consistencies of misinformation, omission, and mistake,”2 and to attend to “the archive’s granular rather than seamless texture, to the rough surface that mottles its hue and shapes its form.”3 Scholarly accounts of the Majie describe their socio-economic status and cultural significance, but intimate details of their found kinships were sourced through the vernacular, such as in offhand comments by members of Chinese clan associations, Facebook posts, or short stories.

The Moon is Wet centres on three migratory characters throughout Singapore’s history: the Chinese sea goddess Mazu4, a Majie and an Indonesian domestic worker, Monic. Each of them speaks a different language: Hokkien, Cantonese and Indonesian, respectively, existing across fluid timelines. Through paralleling and, at times, addressing one another, the three are related in a proposed spectral kinship, one that binds despite geographical or biological chasms, and an alternative foundation to the forefather historicity in Singapore.

This leaning toward speculative ancestry is also personal; it is my response to the rupture that many of us with diasporic heritage face: the silences of family members, either due to a refusal to acknowledge the past or their own gaps in memory and knowledge. One can only hazard a guess as to why my elders have chosen silence; I assume that their lack of formal education has not encouraged them to articulate their interiority either. My grandmother is illiterate, while my mother’s generation, including my mother herself, did not finish their education because funds meant for school often went to the sons/males in the family. Mostly well-versed in Hokkien and Cantonese, they were likely further hampered by language policies like the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979, which, among other initiatives, stamped out Chinese dialect programmes on radio and television for more than thirty years, slashing the number of those who spoke dialect at home from 81.4% in 1980 to 11.8% in 2020.

As a later-generation family member coming to terms with such personal and structural violences, coupled with the Confucian values my family honoured and the silences they upheld, I am left with much room to imagine how thousands of years of ancestry have led me to stare back at this unlit path.

“Critical fabulation,”5 to borrow Saidiya Hartman’s term, enables a web of relations that frees rather than closes in; it is an “impossible writing”6 which attempts to imagine fuller truths than what existing records offer. When archives of the rich interiorities of women throughout history are scant or not made legible, artistic practice is a door to the previously unimaginable.

The search for landscapes in Singapore that could speak to this portal for dreaming led me to set the film along the intertidal zone, a coastal area exposed to both high and low tides. This is a place between binaries: land and sea, artifice and reality, day and night. It is also where the first lives are lost as Singapore expands through land reclamation. Since 1822, Singapore has modified its landmass by 25%, amounting to innumerable intertidal creatures dredged up and buried by the engines of state-driven progress. Intertidal life can take decades, if at all, to return.

It was also at the coast, specifically along Telok Ayer Street, in what is now Singapore’s Central Business District, that the most well-known Mazu temple, Thian Hock Keng, was built in 1839. Its steps once led to the sea, but the sea is now no longer visible or audible from there.

Mazu was the patron deity of seafaring communities hailing from ancient southeastern China. In her human form, she was a mute girl named Lin Moniang (in Mandarin, mo means mute and niang means girl or woman) who had saved her family from a disastrous storm through a premonition after falling asleep while weaving at the loom. At the age of 28, unmarried, she transcended into the divine and became a deity. Early migrants, particularly those from Fujian, brought Mazu worship over to Singapore. As Singapore’s relationship with the sea grew less interdependent and more transactional, the worship of Mazu simultaneously declined locally. This is in contrast to how Mazu worship has experienced a regional surge, particularly in Taiwan, where she is considered the main deity. Even Beijing has begun using her as a tool of political unity.

Her image is one of benevolence, a maternal soothing presence that one has come to expect of goddesses. Yet, in one version of events, Mazu rejects dutiful marital obligations after subduing and subsequently hiring the two demons, Quanliyan and Shunfenger, who sought to marry her. The two, now her bodyguards, flank her on either side in temples. Perhaps these glimpses of female figures subverting their destiny have always existed, even if not read as such.

While conducting research in preparation for the film, I visited various Mazu temples in Singapore, many of which had moved multiple times over the last 50 years. The Mazu temple that was once at the mouth of the Serangoon River, ban gang (“half-port” in English), for example, first moved to Pulau Ubin, then to xin gang (“new-port” or Seng Kang) at Rivervale Crescent, where it shares a parking lot with three other deities. It is an ironic fact in step with Singapore’s development. Mazu may move across the ocean, but in Singapore, Mazu also moves across the land. By holding up a mirror to Singapore’s relationship with its natural environment, Mazu serves as a marker for the shifting sands of progress.

Her position also mirrors the shift in the linguistic landscape. At the beginning of The Moon is Wet, Mazu recites a folk song in Hokkien. It is a guo fan ge (过番歌), a poetic song of migration, sung by migrants arriving in Singapore from Anxi and Quanzhou in Fujian province. It is a literary mode of articulation that is rarely found now among contemporary Hokkien speakers in Singapore.

Yet, finding this song was key to the film’s approach, as it created space for a convergence of dialectical media. The Majie sings in a capella to a Cantopop classic, Anita Mui’s Like an Old Friend is Coming, itself the soundtrack to a film about two sworn sisters in Fujian’s Hui An, titled Twin Bracelets; while Monic, typical of her Sunday day-off routine, croons to Indonesian dangdut and funkot songs in a karaoke room. At one point, the lyrics Tertipu aku tertipu / Dengan janji manismu (I was deceived, I was deceived / By your sweet promises) from the song Janda Manisku plays in the background, as Monic recounts how she has fallen in and out of love.

For context, the Singapore government introduced the Foreign Maid Scheme in 1978, which regulated the employment of Foreign or Overseas Domestic Workers (F/ODWs), many of whom were from neighbouring Southeast Asian countries. This cemented the transition from the Majie to the contemporary domestic worker figure that we know today.

Yet, there is little in the public archive about the personal desires of domestic workers in Singapore. Francisca Yuenki Lai’s Maid to Queer: Asian Labor Migration and Female Same-Sex Desires, published in 2021, is a seminal book about foreign domestic workers and their non-heteronormative desires in a host city. Set in Hong Kong, the book puts forth how identities and desires can ebb and flow, contextualised by the immediate environment that enables them.

The intimate lives of domestic workers are regulated by the state. In 1986, marriage between domestic workers and Singaporeans was banned. Foreign domestic workers are still required to undergo medical check-ups once every six months, which include tests for pregnancy and STDs. The Ministry of Manpower states that if the domestic worker fails the exam, employers “must cancel her work permit and send her home immediately.”

Neferti X. M. Tadiar coined the term “remaindered life” to describe the conditions under which global capitalism has rendered lives marginal, and it is this lens that continues to be pressing when looking at domestic labour.

In the film, Monic is a domestic worker from Indonesia who identifies as pelangi, the Indonesian and Malay word for “rainbow.” She describes how she only discovered what it was after arriving in Singapore. Her community of pelangi friends, all of whom are domestic workers, live out their desires precisely because they are away from their place of origin and, ironically, because pelangi-ness is invisible and undetected by their host.

The act of migration can also lead to the opening of another side of oneself. Through the process of making The Moon is Wet, I consider that, by virtue of its status as a port and palimpsest, Singapore has perhaps served as a portal for specific temporalities to exist. This in-between space renders the construction of the nation a much more delicate exercise of the imagination.

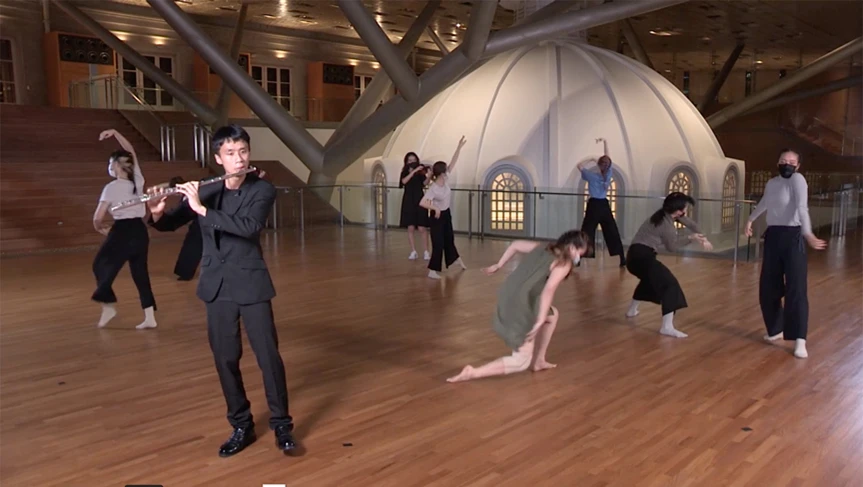

The work’s display environment is a material extension of this rumination. Parting a string curtain, the viewer enters a round, blue-carpeted room to see three curved projections. Each story unfolds in timed segments; one can never view the whole film at once but must submit to the temporality that this cocoon offers.

In her book, Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora, Gayatri Gopinath proposes a “queer diasporic optic” which reconfigures ideas of home, locality and the nation-state. She calls for “feeling backwards,” to access “the shadow spaces of the past and bring them into our frame of the present.” In speculating on lineage and belonging, I find myself travelling twice: once from Berlin, where I am based, back to Singapore, and again to ports of departure before that.

The final shot of the film shows a cuttlefish bone slowly being carried away by the tide. Such bones were once used as material to carve figurines for worship during the Seven Sisters Festival, in which the Majie played a large organising role. These gestures of honour have long left our shores. Yet, in the ambivalence of such an ending, I hope to hold open a door for the possibility of past lives recurring, to confront us once again with what we wish to do with their legacy.

The Moon is Wet is on view until 23 February 2026 at PalaisPopulaire in Berlin, as part of the author’s solo exhibition, Make a travel deep of your inside, and don’t forget me to take.

Notes

1. All images, unless otherwise stated, are courtesy of the author.

2. Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton University Press, 2009), 20.

3. Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, 53.

4. Mazu is a deity believed to have originated from Fujian, where many migrants departed for Singapore. Her relation to Singapore will be elaborated upon further in the essay.

5. Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14.

6. Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 1–14.