Wishful Images at NUS Museum

In this article, Choy Myn reviews Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form, an exhibition presented by NUS Museum. As a history student, Choy Myn has seen how Cold War history often focuses on the great men and the big players like the United States, Soviet Union and their leaders—this review delves into why she finds the highly personal, grassroots approach of this exhibition extremely refreshing. This piece was written for “Time Traveller: the Curatorial in Southeast Asia” module, offered as part of the Minor in Art History at NUS

Still from My Mentor, Cheng Yingzhen

2010, Taiwan

27 minutes, video

Image taken from the exhibition guide, Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form

The Minor in Art History at National University of Singapore (NUS) is jointly offered by the NUS Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences and National Gallery Singapore. A number of the modules offered have been developed by the Gallery's curators, and are also taught by them. This piece was written for the module "Time Traveller: the Curatorial in Southeast Asia," which provides students with the opportunity. to familiarise themselves with the history, methodologies, and theories of the region’s incredibly diverse art exhibitions.

Introduction

Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form was an exhibition at NUS Museum from 22 September 2020 to 15 October 2022, and was the brainchild of curator Dr Hsu Fang-Tze's three-month Okinawan residency in 2018.1 Through events like the 1970s Koza Riots and Lusaka Conference, the exhibition aims to expose visitors to lesser-known, officially suppressed yet intriguing and significant development within the Asian Cold War, which is itself often ignored in favour of Euromerican discourses.2 However, more importantly, inspired by Ernst Bloch's philosophy of "wishful images," Hsu hoped to demonstrate the common idealism and postcolonial themes shared by seemingly disparate struggles against power.3 In an age dominated by colonial, racial and environmental discourse, this review opines that Wishful Images represents a relevant, refreshing attempt at problematising and deepening the viewer's perceptions of the grand Cold War narrative by introducing newer, more personal perspectives of the event. However, as the exhibition takes place in a university museum, its educational intent could have been better achieved if its rich concepts were better communicated to its audience of predominately university students. This conclusion will be supported by evaluating how well the artist and artworks were chosen, how thoughtful the use of space is and how good the viewer's experience is.

Artist and Artwork Choice

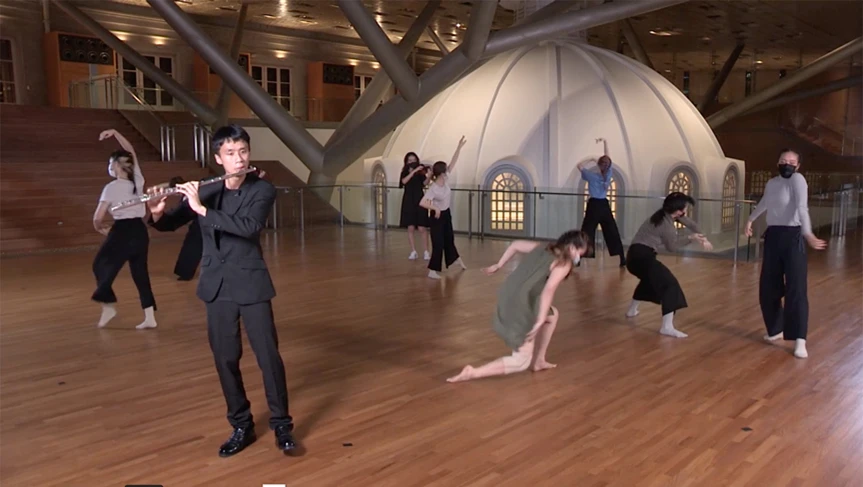

Kao Chung-Li

Still from My Mentor, Cheng Yingzhen

2010, Taiwan

27 minutes, video

Image taken from the exhibition guide, Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form

Wishful Images' eclectic choice of artists and artworks complicate conventional Euromerican Cold War narratives by showcasing a more nuanced, personal perspective on the historical event. Kao Chung-Li's My Mentor, Cheng Yingzhen (fig. 1) is one of the first works the visitors see upon entering the gallery. As an artist, Kao is a thematically appropriate choice as his primary oeuvre investigates connections between history and one's personal biography.4 My Mentor is also an apt choice. The artwork criticises "outcast socialist intellectual" Cheng Yingzhen's persecution in Taiwan, a country which often extols its Western-inspired democratic and free speech values while denigrating its mainland counterparts for human rights abuses.5 The viewer is confronted by these hypocrisies committed by the “democratic” Taiwanese government and the complicity of those who supported them, like the USA. Hence, the viewer is also forced to re-evaluate the conventional Cold War portrayal of USA as the worlds' saviour.

Kuniyoshi Kazuo

Collection of Photographs

1970—1978, Koza, Japan

Photographs

Image courtesy of Choy Myn

Following Kao's work is a selection of Kuniyoshi Kazuo's photographs (fig. 2). As an artist, Kazuo is a fitting choice as his native Koza roots—the place which every selected photograph focuses on—and his commitment to journalism and depicting what he regards as the truth add a strong personal connection and conviction to the exhibition's foundational concept.6 In his photographs documenting the Koza Riots, Kazuo shatters the image of the USA being an anti-imperialist, benevolent ruler by documenting a boiling point in Okinawan nationalism and dissatisfaction with American presence and control. He further questions America's clean representation by highlighting resistance against America's discriminative and destructive policies through his record of the Martin Luther King and Kennedy Brothers' civil rights memorial marches, the racially segregated entertainment town of Terua and the anti-Vietnam protests.7

Nguyen Trinh Tri

Still from Eleven Men

2017, Vietnam

28 minutes, HD video

Image taken from the exhibition guide, Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form

Following this is Nguyen Trinh Tri's video Eleven Men (fig. 3). Inspired by Kafka's Eleven Sons, the video compiles 12 film excerpts depicting the different romantic relationships Nha Quynh's characters have had over her 30-year career under the state-controlled Vietnam Feature Film Studio.8 Indeed, the work is structured around a woman's "life," thus reclaiming Vietnamese cinema for women as their roles are expanded beyond "something to be looked at."9 However, the film is more humanist than "pre-determinedly feminist."10 With the male characters now portraying the role women once played in these films, Nguyen emphasises how men and women alike have been exploited for national agendas. This refreshing, more sympathetic perspective on the Vietnamese gender equality movement is also combined with how the viewer can grasp different eras of Vietnamese local and national history as masculine roles evolve over time, an aspect not often considered in Western-centric accounts of the Vietnam War. The work's multiple layers, coupled with Nguyen's proof that enlightened values can be derived from “draconian” state-controlled media, support the exhibition's intentions of highlighting little-known perspectives as well.

Aya Rodriguez-Izumi and Jose Rodriguez

Okinawa's Tragedy from the Last Battle of WWII

Prints are from 1986, Okinawa

Audio recordings and text are from 2020, New York

Installation, reproduction of prints, audio and text

Narrators: Aya Rodriguez-Izumi, Jose Rodriguez and Noriko Rodriguez

Image taken from the exhibition guide, Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form

Last in this particular section is Okinawa's Tragedy: Echoes from the Last Battle of WWII. Jose Rodriguez's woodblock prints (fig. 4) support the exhibition's intentions by featuring the original illustrations from the first book documenting often-ignored, first-hand local perspectives of the Battle of Okinawa.11 Moreover, by supplementing these 1980s woodblock prints with contemporary audio recordings of the artist and his family reading excerpts from the book, the traumatic event's relevancy—even today—and the need to remember these personal, yet affective memories Is imparted to the viewer.

Lucy Davis

Still from Jalan Jati (Teak Road)

2012, Singapore

23 minutes, film

Image taken from the exhibition guide, Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form

Nevertheless, Lucy Davis and her artworks were rather mismatched thematically and conceptually, especially following the Rodriguez-lzumis' highly intimate and personal work. Prints of teak trees, furniture and related businesses were displayed physically and digitally in her stop-motion animation Jalan Jati (fig. 5). Indeed, like other selected works, Davis' artworks criticise colonialism by turning the typical narrative on its head.12 Instead of the environment and a natural product being used and rendered for colonial gain, the teak is given agency; it is depicted as seemingly having exploited human greed and effort to “colonise Southeast Asia,” as demonstrated their wide geographical distribution.13 However, the artwork mostly references traditional colonialism rather than the USA neo-colonialism theme shared by the other artworks. Furthermore, its “non-human perspective” clashes with the intimate storytelling used by the other four works.

Use of Space

"Passageway" entry into the darkened exhibition space

Image courtesy of Choy Myn

Wishful Images' use of space enhances the viewer's appreciation of its overarching concepts by establishing relationships between the artworks and the contextual documents. Entrance into the gallery is via a space akin to a passageway (fig. 6) leading to a darkened gallery space. The dimmed lighting enables visitors to view the two films clearly but also prevents the space to from becoming a decontextualised “white cube” which contradicts the exhibition's primary purpose.14 Additionally, the experience also simulates how the viewer is going into “the historical void” to “unearth” these forgotten historical perspectives.

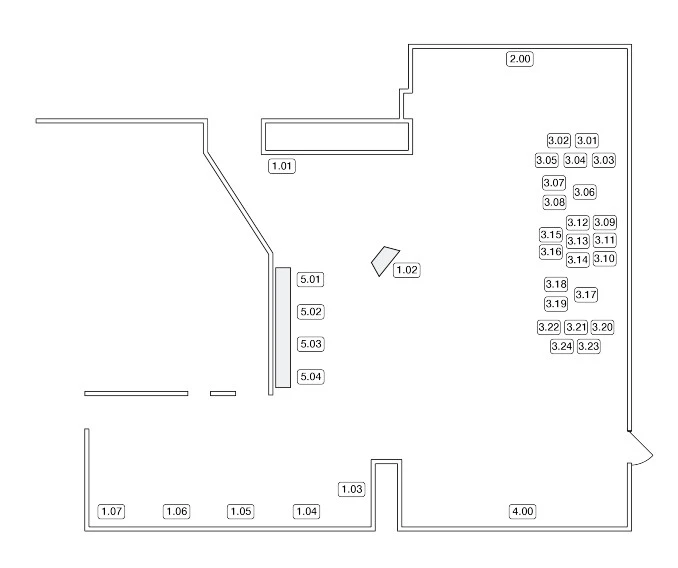

Exhibition floorplan

Image taken from the exhibition guide, Wishful Images: When Microhistories Take Form

The artworks are positioned strategically too. According to the floorplan (fig. 7), the two Okinawan works are situated across each other. This enables the viewer to trace Okinawa's continued strife under Japanese and USA rule. By equalising them, the typical Cold War narrative is challenged. This also means that visitors can better empathise with the nationalist agendas expressed by the excerpts of Kawamitsu Shinichi's manifesto on the gallery walls. Additionally, consistently citing Shinichi's work in the space builds dialogue and highlights the similarities between the Okinawan and non-Okinawan works. These connections reflect Ernst Bloch's philosophy of how humans inherently have an “anticipatory consciousness”—a wish for a better future.15 Though they represent physically and geopolitically opposed positions in the gallery and in history, both Kao’s and Nguyen’s works criticise their countries' ruling regimes and ideologies, just as their Okinawan counterparts have done. Similarly, despite their wildly different contexts, all four works reflect Bloch's philosophy; together, they demonstrate a universal aspiration towards a peaceful country without discrimination, the utopian vision implied by Shinichi's work. Bloch's idea that “wishful images” motivate people to pursue this vision is also implied by the exhibition's selections of works made with more modern media, like photography and film.16 Additionally, the four artworks' refusal to be politically polarised also reflects the Non-Aligned movement's intentions, though how this connect exactly to the Lusaka Conference, especially after the strong, direct references to the Koza Riots, is unclear.

Jalan Jati's central location, between the four other artworks

Image courtesy of Choy Myn

With these considerations in mind, Jalan Jati occupying a central location between the other four works is unfortunate (fig. 8), considering its thematic and conceptual mismatch. Furthermore, while the timber samples are an interesting supporting artefact as they are evidence of environmental colonialism, they are placed awkwardly at the exhibition's beginning before Davis' works.17 Hence, it is deprived of much-needed context. Additionally, segregating Davis' prints from the main exhibition area also highlights the mismatch between them.

Didactics

Lastly, Wishful Images' intentions and concepts could have been better communicated to its predominantly university student audience if the exhibition's didactics were more organised and accessible. Exhibition labels in the gallery space would have increased visitor comprehension of the artworks, their relationships with other exhibition elements and the exhibition's narrative. While there is an online guide containing the curatorial intentions, pictures and labels, one wishes for higher quality and larger sized pictures. Furthermore, the shift from brochure to online guide could have been taken better advantage of. Following examples like Vdrome, the curator's interview and insight from the accompanying Noise of Time talks could have been included in that online guide. Furthermore, as an educational institution, regular new content like exhibition reviews or intern experiences with the exhibition would be easier to upload. This could draw new crowds or persuade others to return and re-evaluate the exhibition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Wishful Images' content choices, space usage and visitor's experience mostly support its intentions of problematising typical Cold War narratives by demonstrating the significance of dissenting “microhistories.” However, better didactics would have bolstered better comprehension and retention of the exhibition's rich meanings in its target audience.

Notes

- "In Conversation with Hsu Fang-Tze, curator of Wishful Images,” CFA Spotlight, https://cfa.nus.edu.sg/spotlight/in-conversation-with-hsu-fang-tze-curator-of-wishful-images/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- "Kao Chung Li," TKG+, https://www.tkgplus.com/en/artists/27-/biography/. (accessed 8 March 2021)

- "In Conversation with Hsu Fang-Tze”

- Ibid.

- "[Talk Series] Noise of Time," CFA Spotlight, https://cfa.nus.edu.sg/whats on/talk-series-noise-of-time/ (accessed 8 March 2021)

- "Nguyen Trinh Tri: "Eleven Men"," Vdrome, https://www.vdrome.org/nguyen-trinh-thi. (accessed 8 March 2021)

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- "Okinawa's Tragedy: Echoes from the Last Battle of WWII," Aya-Rodriguez Izumi, http s://iamaya.com/section/501574-Okinawa-s-Tragedy.html (accessed 9 March 2021)

- Lucy Davis, The Migrant Ecologies Project: Jalan Jati (Teak Road) (Singapore: Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, 2013), 86.

- Ibid.

- 1Simon Sheikh. "Positively White Cube Revisited." e-f/ux 3 (2009).

- Vincent Geoghegan, "Bloch, Ernst," in Encyclopaedia of Modern Political Thought, ed. Gregory Claeys (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Ltd., 2013), 94.

- Jack Zipes, “Ernst Bloch's Enlightened View of the Fairy Tale and Utopian Longing." in Ernst Bloch: The Pugnacious Philosopher of Hope (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2019), 105.

- "In Conversation with Hsu Fang-Tze.”

Bibliography

Davis, Lucy. The Migrant Ecologies Project: Jalan Jati (Teak Road). Singapore: Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, 2013.

Geoghegan, Vincent. "Bloch, Ernst." In Encyclopaedia of Modem Political Thought, 94-94. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Ltd., 2013.

"In Conversation with Hsu Fang-Tze, curator of Wishful Images." CFA Spotlight. https://cfa.nus.edu.sg/spotlight/in-conversation-with-hsu fang-tze-curator-of-wishful-images/.

"Kao Chung Li." TKG+. https://www.tkgplus.com/en/artists27-/biography/ (accessed 8 March 2021).

Nguyen Trinh Tri: "Eleven Men"." Vdrome. https://www.vdrome.org/nguyen-trinh-thi (accessed 8 March 2021).

Sheikh, Simon. "Positively White Cube Revisited." e-flux 3 (2009). "[Talk Series] Noise of Time." CFA Spotlight. https://cfa.nus.edu.sg/whats-on/talk-series-noise-of-time/ (accessed 8 March 2021).

Zipes, Jack. "Ernst Bloch's Enlightened View of the Fairy Tale and Utopian Longing." In Ernst Bloch: The Pugnacious Philosopher of Hope, 103-118. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2019.