Encounter captivating French Impressionist works and their enduring relevance at National Gallery Singapore’s blockbuster exhibition Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Come face-to-face with over 100 iconic Impressionist works at Southeast Asia’s largest exhibition of French Impressionism from the world-renowned collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

.png)

SINGAPORE, 7 November 2025 – National Gallery Singapore presents Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston – Southeast Asia’s largest ever showing of French Impressionism. This must-see blockbuster offers visitors an extraordinary opportunity to encounter works by iconic artists such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, and Edgar Degas, while exploring the enduring influence of modernity and its continued relevance today.

Opening on 14 November 2025, the exhibition features more than 100 artworks by 25 of the movement’s key artists, including 17 paintings by Claude Monet. This world-class collection is on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA Boston) – which has one of the largest and most comprehensive holdings of Impressionist art outside France.

Developed jointly by the National Gallery Singapore and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the exhibition offers a fresh perspective on Impressionism and its dialogue with the rapidly changing world of the late 19th century. It explores how French Impressionists transformed the way light, colour, and everyday life were portrayed, capturing the spirit of modernity in ways that still resonate today. Set against the backdrop of sweeping social and cultural change, the works address themes that remain powerfully relevant — from rural labour and the rise of tourism to urban transformation and shifting gender roles — underscoring Impressionism’s lasting influence on how we see and experience the world.

Immerse in the vibrant world of Impressionism

Organised into seven thematic sections, Seeking the Open Air, Plein Air Impressionism, Labour and Leisure on the Water, Shared Ambitions, Modern Encounters, Reimagining the Commonplace, and Monet - Moment and Memory, the exhibition offers a distinctive presentation of the MFA’s collection.

The exhibition design heightens the immediacy of the Impressionists’ artworks. Spanning three gallery spaces, a cool-toned, contemporary aesthetic situates Impressionism within the present. Archival materials, such as historical photographs and posters, are displayed on a monumental scale throughout the exhibition, reflecting how life in the modern era of the Impressionists was one of constant dynamism and change while adding visual layers that deepen visitors’ engagement with the paintings and prints on display.

Visitors can also discover the legacy of Impressionism in Southeast Asia through three reflection zones and interactive learning stations across the galleries. Called ARTeliers, these spaces highlight how Impressionist techniques were adapted in the region. A specially commissioned animated film traces the rise of plein air painting in Vietnam, while another section explores how Singapore artist Georgette Chen captured the play of light and reflection in works like Singapore Waterfront (1963). Visitors can even try brushstrokes inspired by her style. A third ARTelier focuses on Singaporean artist Lim Yew Kuan, whose iterative prints recall the approach of Camille Pissarro, featured in the exhibition.

A fresh lens on a world-renowned collection

“Through our close collaboration with the MFA, we are proud to bring one of the world’s greatest collections of Impressionism to the Gallery,” says Dr Eugene Tan, CEO and Director of National Gallery Singapore. “Into the Modern presents these seminal works through a distinct curatorial lens that connects Impressionism to contemporary conversations about society, the environment, and urban life. At the same time, it explores the legacy of Impressionism in Southeast Asia. Presenting the exhibition in this way highlights the Gallery’s role in facilitating dialogue that connects the art of Singapore, Southeast Asia and the rest of the world, in keeping with Singapore’s role as a nexus where global and regional art histories intersect. This exhibition reflects our commitment to making world-class art accessible to audiences in Singapore and Southeast Asia, while opening new perspectives on its enduring significance.”

“It is our great honour to be the first US partner of National Gallery Singapore, and to share these timeless masterpieces with visitors from Singapore and throughout Southeast Asia,” said Mr Pierre Terjanian, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. “This project exemplifies the power of art to connect people across time, cultures, and place, to ideas past and present. We are extremely proud of the collaboration between our two institutions to bring this exhibition to life. This partnership has fostered new insights into the MFA's Impressionist collection, bringing fresh perspectives on iconic works by artists like Monet, Renoir, and Degas. From rural farmlands to coastal resort towns or sites of urban leisure, these 19th-century visions of modern life continue to inspire contemporary audiences not only through their beauty, but through their ability to underscore issues that still impact all of us today, more than a century after these works were made.”

The exhibition opens with Seeking the Open Air, an immersive introduction with projected archival photographs that transport visitors into the forested landscapes that inspired mid-19th-century artists. During this era of rapid change — marked by new railways, roads, and industrialisation — artists sought to capture the rustic beauty of nature before it vanished. Painter Théodore Rousseau, an early advocate for land conservation, successfully petitioned the French government to protect parts of the Fontainebleau forest as a national preserve. By painting outdoors, artists developed naturalistic and nuanced depictions of forests and farmlands, laying the foundations for the plein air (open-air) approach later embraced by the Impressionists.

Building on these beginnings, Plein Air Impressionism explores how Impressionist artists transformed outdoor painting into a hallmark of the movement. Featuring a work by Edgar Degas first shown at the inaugural Impressionist exhibition in April 1874, this section traces the early evolution of the style. Painting en plein air, artists like Pierre Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet captured shifting light and fleeting moments of everyday life with bright palettes and expressive brushwork — reflecting the immediacy and dynamism of modernity.

In Labour and Leisure on the Water, visitors encounter late-19th-century touristic posters that celebrated Normandy’s coastal resorts, such as Trouville — popular with both holidaymakers and painters of the time. The vibrant works on display range from intimate harbour scenes to sweeping seascapes, illustrating how expanding railways, steamboats, and ports made travel newly accessible. Water becomes the unifying motif, reflecting both the rhythms of work and the pleasures of leisure, and revealing how artists captured the changing relationship between people and place.

The fourth section, Shared Ambitions, delves into the collective spirit of the Impressionists — not only their shared artistic pursuit of modern life, but also their political sympathies. Prints and paintings by Camille Pissarro depict rural labour and scenes of everyday work, reflecting his belief in social equality and the dignity of labour. Visitors are invited to “look twice”: what first appears as a picturesque landscape often contains subtle commentaries on social and political realities.

Modern Encounters transports visitors to the vibrant streets and interiors of late-19th-century Paris. Massive urban redevelopment had reshaped the city, inspiring artists to capture its new rhythms — its cafés, boulevards, and domestic spaces. Through suspended panels of archival photographs and posters, the section immerses visitors in the social fabric of modern Paris. Highlights include a recently rediscovered self-portrait by Victorine Meurent, once famed as Édouard Manet’s favourite model. Displayed alongside Manet’s depictions of her, Meurent’s painting offers a rare opportunity to see how she viewed herself — as both subject and artist — in the modern world she helped define.

Reimagining the Commonplace looks at how still life became a favourite subject for the Impressionists and their peers — a testing ground for new ideas. By reinventing a familiar genre, these artists broke away from traditional rules of perspective and composition. In the quiet of their studios, they experimented with form, texture, and colour, using expressive brushwork and daring arrangements to find fresh beauty in ordinary objects.

The exhibition concludes with Monet — Moment and Memory, a striking finale featuring nine iconic works by Claude Monet, arguably the world’s most popular Impressionist artist. Displayed along gently curved walls, the presentation invites visitors to follow a contemplative path through Monet’s evolving explorations of light, colour, and atmosphere. Each canvas bears his unmistakable touch — alive with movement and luminosity — revealing why his art continues to captivate audiences worldwide. The journey ends with the only known film footage of Monet, shot in 1915, offering a rare glimpse of the artist at work and underscoring the Impressionists’ connection to the dawn of the modern, cinematic age.

Ms Lian Pek, Singtel’s Vice President of Group Corporate Affairs and Investor Relations, said, “We are immensely pleased to support the Into the Modern landmark impressionism showcase at the Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery of the National Gallery. Who would have thought that the iconic masterpieces of Monet, Cezanne and Degas would one day come to the shores of our little red dot for Singaporeans and visitors to enjoy? With the exhibition also spotlighting the legacy of impressionism in Southeast Asia, this is not just a showcase of a French art movement but an exploration of the connections and conversations that it inspired globally. Having connected communities across the world for over 140 years, this is something that resonates deeply with us at Singtel.”

“J.P. Morgan is proud to be the Presenting Partner of Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” says Wai Mei Hong, Senior Country Officer for J.P. Morgan Singapore. “We are delighted to support this landmark exhibition, which brings world-class Impressionist works to a wide audience in Singapore, and fosters greater appreciation for the arts.”

“Singapore Tourism Board is delighted to support National Gallery Singapore’s landmark Impressionist exhibition, featuring masterpieces from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, that have never been shown in Southeast Asia before. This rare opportunity to experience the works by Monet, Renoir, Degas, and other celebrated Impressionist artists reflects Singapore’s growing reputation as a regional cultural destination that offers unique, high-calibre experiences that appeal to both locals and visitors,” said Ms Guo Teyi, Director, Leisure Events, Singapore Tourism Board.

Impressionist-themed partnerships and merchandise

For a delightful taste of Impressionism, Pierre Hermé Paris presents Into the Haute Pâtisserie, an exclusive pop-up at National Gallery Singapore from 14 November to 31 December 2025, in collaboration with Resorts World Sentosa and Stellaire. Visitors can indulge in Pierre Hermé’s signature macarons, available in special-edition box sets adorned with two iconic Impressionist artworks featured in the exhibition.

To extend the experience beyond the galleries, Fairmont Singapore’s ANTI:DOTE will offer An Impressionist-Inspired Afternoon Tea, a menu of artfully plated sweet and savoury delights inspired by Into the Modern. Available from 6 November 2025 to 31 January 2026, this high tea celebrates the colour, creativity, and charm of Impressionism through an exquisite culinary interpretation.

The Gallery Store by ABRY will also launch a line of exclusive exhibition merchandise, available both online and in-store. Visitors can take home a piece of the experience with items such as the exhibition catalogue, tote bag, umbrella, tea towel, coasters, and more.

Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston at National Gallery Singapore

Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston runs from 14 November 2025 to 1 March 2026, and is organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in partnership with National Gallery Singapore.

Visitors may purchase Special Exhibition Passes via the Gallery’s website at $25 each ($15 for Singapore Citizens and Permanent Residents) to visit the exhibition at the Singtel Special Exhibition Galleries.

The exhibition would not be possible without the generous support of the exhibition’s Series Partner Singtel, Presenting Partner J.P. Morgan and Strategic Partner the Singapore Tourism Board.

Media assets are available through this link.

- Annex A: Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Sections and Key Artworks

- Annex B: Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Exhibition Brand Partnerships and Programmes

Annex A: Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Sections and Key Artwork

Seeking the Open Air

The exhibition begins with Seeking the Open Air, tracing how mid-19th-century painters turned to the French countryside as both subject and sanctuary. This section features an immersive design element of archival panels and projections of trees which place visitors within the forested landscapes that inspired mid-19th-century artists. Driving a new movement in landscape painting, artists of the Barbizon School embraced direct observation, painting outdoors to capture the atmosphere of farmland, forest, and rural life. Around the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau, they developed palettes attuned to the shifting light and colours of the landscape, laying the foundations for the plein air practices later adopted by the Impressionists.

At the same time, these landscapes bore witness to change. Expanding roads, railways, and industrial demands stripped the forest of wood and stone to fuel Paris’s growth, even as artists sought to preserve its rustic beauty and quiet reverence on canvas. Théodore Rousseau, whose ecological activism contributed to establishing parts of Fontainebleau forest as the world’s first nature reserve, contrasts the grandeur of towering trees and open land with the much smaller figures of wood gatherers in Edge of the Woods (Plain of Barbizon near Fontainebleau) (c. 1850–1860), situating them within the landscape to suggest human scale in nature. Rousseau’s careful observations became an enduring influence on artists such as Claude Monet, whose Woodgatherers at the Edge of the Forest (c. 1863) echoes Rousseau’s tranquil scene but with a lighter palette and more spontaneous brushwork that foreshadows key qualities of Impressionism.

Plein Air Impressionism

Plein Air Impressionism illustrates how the artists, today celebrated as the Impressionists, made painting outdoors a defining part of their practice while also developing their own distinctive styles. First exhibiting together in April 1874, they sought to capture ephemeral moments in nature and chance encounters in public spaces. Painting directly in front of their subjects allowed them to observe light, atmosphere, and everyday activity with immediacy, resulting in bright colour palettes, expressive brushwork, and nuanced portrayals of modern life.

In Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Woman with a Parasol and Small Child on a Sunlit Hillside (c. 1874–76), soft, feathery brushstrokes depict a woman, likely Claude Monet’s wife, Camille Monet, sitting gracefully on a hillside, her white dress dappled with shifting sunlight, while a small child wanders into the background, seemingly unaware of the painter’s presence. Edgar Degas’ At the Races in the Countryside (1869), shown at the First Impressionist Exhibition, foregrounds a family scene centred on a baby, while mounted onlookers glimpse horses mid-race across a sparse Normandy landscape. Painted in a very different style than Renoir, Degas’ careful observation and unusual cropping nonetheless also convey the sense of a fleeting moment, as if the viewer has stumbled upon the scene. Such examples reveal how the Impressionists turned to the direct experiences of modern life in their work, capturing its atmosphere and transience, and placing fleeting moments at the heart of their art.

Labour and Leisure on the Water

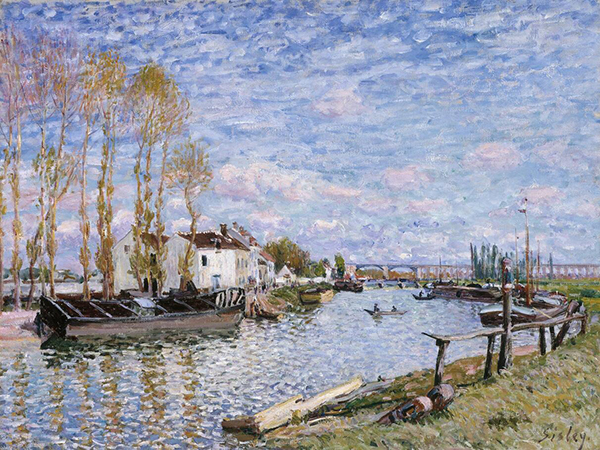

The French landscape underwent significant transformation over the 19th century, shaped by industrial growth, expanding ports, and the increasing importance of waterways for commerce. Artists of the period captured both the picturesque beauty of rivers and coasts and the activities that took place along them, making water a central subject in their work. In Alfred Sisley’s The Loing at Saint-Mammès (1882), the artist depicts Saint-Mammès, where the Loing River meets the Seine, using short, detached brushstrokes to convey the rippling movement of the water. The painting records economic activities on the river, from fishing boats to barges, while the distant Paris-Lyon railroad viaduct hints at industrial expansion. Despite these signs of change, Sisley maintains a tranquil, harmonious composition that reflects the enduring appeal of the rural landscape.

Alongside scenes of labour, waterways also became spaces of leisure. Railways and steamboats made coastal destinations more accessible, and the rise of seaside tourism inspired artists to capture urbanites enjoying holidays. Eugène Louis Boudin’s Fashionable Figures on the Beach (1865) presents a luminous and detailed view of beachgoers. Through his refined composition, Boudin utilizes careful observation to portray both the social rhythms of leisure and the evolving culture of tourism. By depicting both work and play along rivers, canals, and coasts, artists explored the full spectrum of modern life, conveying its activity, travel, and pleasures.

Shared Ambitions

Common goals united the Impressionists: to depict modern life as they experienced it and to exhibit their work publicly. Camille Pissarro was a central and constant presence within the group, participating in all eight Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886. His connections to different members of the circle are evident in this section, reflecting both mentorship and collaboration. He worked alongside contemporaries such as Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin and also remained open to new approaches and willing to learn from younger artists, exemplifying the spirit of experimentation that characterised Impressionism.

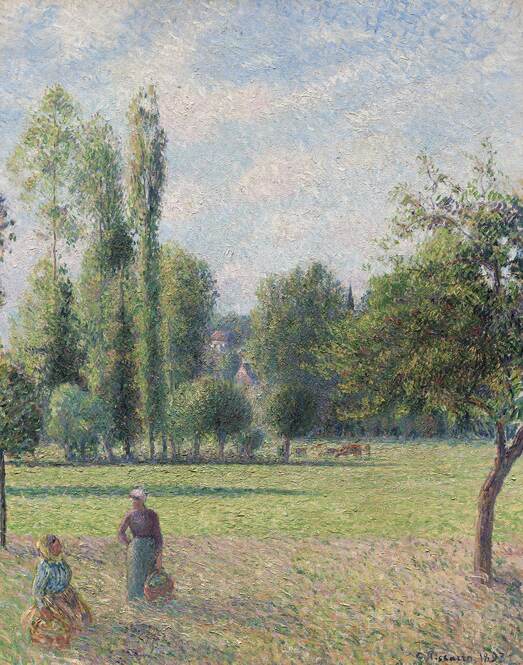

Two Peasant Women in a Meadow (Le Pré) (1893) illustrates Pissarro’s effort to merge the precision of a more Pointillist brushstroke with the spontaneity and freedom of Impressionist observation. The painting shows two women conversing as cows graze in the background, rendered in small, careful strokes that convey the textures of the field, fabrics, trees and sky, capturing a moment that feels lived and immediate.

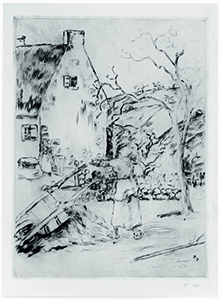

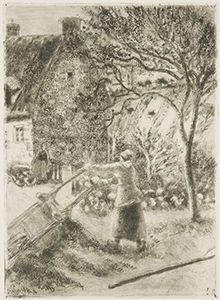

Beyond technical experimentation, Pissarro’s works reflect his social and political ideals, which resonate with his broader engagement with contemporary society and everyday life. Unique to the Gallery’s presentation, visitors will encounter Pissarro’s experimental print series Woman Emptying a Wheelbarrow (1880). Three prints from the series which share this motif will be displayed. He devoted careful attention to an ordinary subject, emphasising the labour of the working class. Each version of the print was created by augmenting the initial base plate and varying the inking for each impression, introducing different visual and textural effects. The layering of etching, drypoint, and aquatint allowed forms to evolve across states, blending precision with the painterly expressiveness of Impressionism.

Modern Encounters

Paris underwent a significant transformation in the mid-19th century, as urban revitalisation projects reshaped the city’s layout and appearance. Poorer neighbourhoods were demolished to make way for vast boulevards and grand apartment buildings, while suburban areas became popular retreats for city dwellers. New entertainment venues, including cafés, theatres, parks, and racetracks, encouraged social interaction in new ways. In this context, Paris became more open and connected between different parts of the city.

Artists captured the vibrancy of the modern city and the subtle shifts in its social life. In Dance at Bougival (1883), Pierre-Auguste Renoir depicts a lively open-air café along the Seine, where people from different social classes gather for the weekly bals des canotiers (boaters’ balls). A dancing couple commands the scene, their movements set against the ground scattered with cigarette butts and discarded flowers. Half-finished beer glasses hint at the casual intimacy and ephemeral pleasures of these lively venues. Intersecting sightlines guide the viewer’s gaze toward the dancers, while the figures in the background create depth and volume. Renoir’s combination of a carefully composed scene with soft, fluid brushwork captures the energy and spontaneity of the moment, offering a vivid glimpse into 19th-century social dynamics that continue to resonate today.

During this period, opportunities for women artists remained limited, yet many sought to assert their place in the art world through study and public exhibition. In Street Singer (c. 1862), Manet captures a figure familiar from the new, urban public spaces of Paris: a female street musician. Manet used his favourite model, Victorine Meurent, to stage the scene. The large-scale painting elevates her presence, with a direct gaze that challenges the viewer and conveys dignity to this generally marginalised figure.

Meurent was not only an artist’s model, but also a dancer and a painter. Shown alongside three images of Meurent produced by Manet, her Self-Portrait (c. 1876), presents a mature, confident woman, rendered with refined attention to the textures of hair, skin, and fabric. This painting was likely the one she had accepted into the 1876 Paris Salon, the annual exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the same year that Manet’s own submissions were rejected. Displayed alongside Manet’s Olympia (Large Plate) (1867), a work for which Meurent also modelled and for which the painted version caused a sensation at the 1865 Salon as a scandalous depiction of a nude prostitute, this pairing underscores Meurent’s dual identity as both model and accomplished artist. It also highlights the evolving roles of women in society and the arts, reflecting their increased agency and visibility. Through these works, visitors are invited to consider not only the individual subjects but also the broader social and cultural transformations that shaped these encounters.

Reimagining the Commonplace

As Impressionists explored the changing rhythms of modern life, they also turned to everyday subjects as a space for experimentation. Still life, traditionally regarded as a minor genre compared with historical or mythological painting, gained new prominence in the 19th century. Its studio-based nature offered artists a controlled environment to transform ordinary objects by exploring composition, light, and brushwork in inventive ways. By engaging with such conventional subjects, Impressionists could subtly challenge artistic norms while developing a distinct visual language.

Berthe Morisot’s work illustrates how Impressionists used familiar genres to push boundaries. In White flowers in a bowl (1885), loose, sketchy brushstrokes convey the blossoms with graceful immediacy, demonstrating both technical skill and expressive freedom that became central to her style. Critics of the time, however, sometimes misinterpreted her avant-garde brushwork as evidence of incompleteness, unfairly attributing it to her gender rather than recognising it as a deliberate technique. Yet Morisot’s achievements speak to her artistic authority: she was a prominent member of the male-dominated Impressionist circle, participating in all but one of the eight Impressionist exhibitions and had also previously achieved mainstream success at the Paris Salon.

Monet — Moment and Memory

The exhibition concludes with a spotlight on Claude Monet, one of the founding figures of the Impressionist movement, with a remarkable array of nine works (a further eight appear elsewhere throughout the exhibition). These paintings reveal why Monet remains so beloved: his vibrant, light-filled canvases capture not only the vitality of nature but also the fleeting sensations of a particular moment. While instantly recognisable as “Monet” in their painterly sensibility, the works display a range of compositions, colour palettes, and treatments of light and shadow.

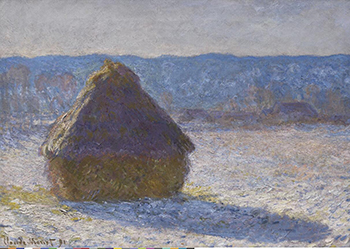

Monet’s method was inseparable from his immersion in nature. Poppy Field in a Hollow near Giverny (1885), a depiction of the lush countryside around his home, demonstrates his sensitivity to both the grandeur and intimacy of the rural landscape. The stacked hay in the middle distance anticipates his iconic Grainstack series from several years later. One example, Grainstack (snow effect) (1891), exemplifies Monet’s study of shifting light and seasonal change. He painted at least twenty-five canvases of grainstacks in Giverny, transforming a familiar subject through time and weather. Here, sunlight glances across a dusting of snow, brightening an otherwise chilly, wintry day. The painting illustrates Monet’s meticulous observation of a single subject under changing conditions, turning an everyday rural view into a meditation on perception, memory, and the passage of time.

Monet’s preoccupation with transient effects reaches its fullest expression in his depictions of water. The Water Lily Pond (1900) reflects his fascination with the water garden he cultivated at Giverny over multiple years. Beneath the arching Japanese-style footbridge, the lily-strewn pond mirrors the surrounding willows, showcasing both the reflective quality of water and the subtle effects of shifting light. The pond became a vast laboratory for Monet’s exploration of the ephemeral qualities of nature over the following decades. Together, these works illuminate Monet’s central idea: preserving the sensation of an instant. His canvases transform fleeting impressions into enduring images, offering viewers not only the memory of a place but the experience of time itself, an approach that was radical in his day and remains profoundly resonant today.