Southeast Asian Futurism through the National Collection

In 1973, the Indonesian polymath and intellectual Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana (STA) presented his paper “The Place of Art in the Psychological, Social and Cultural Reconstruction of the Future. Calling for “a new avant-garde,” he positioned the artist as playing a critical part in building a post-Cold War future. He believed that the aesthetic experience was foundational to societies and culture was a representation of a value system, and that artmaking and appreciation created a a feedback loop between the individual and society. This article features select artworks from Singapore's National Collection that capture the cultural and regional zeitgeist from which STA’s ideas emerged, spotlighting other important artists and futurists.

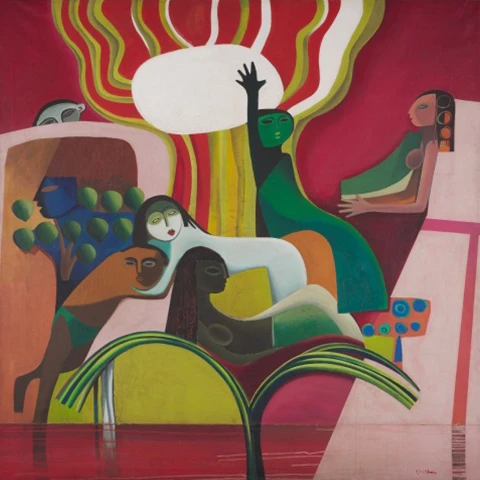

Children of the Sun

1965

Oil on canvas, 230 x 230 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board, Singapore

As a term, “Southeast Asian Futurism” may often be thought of as a philosophy or an aesthetic that imagines human progress often along the lines of accelerated technological advancement. In art history, futurism is typically associated with the early 20th century Italian art movement that emphasised the dynamism of machines in an industrialising society. Italian futurism and the term “futurism” itself was coined by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti to advocate for an avant garde that discarded history and the art of the past for a forward thinking perspective that glorified the machine—the automobile—while repudiating traditional values and institutions like museums and libraries. The Italian movement is known for its complicated associations with the rise of fascism in the lead up to World War I.1

In contemporary art discourses, futurity has informed the theoretical conceptualisation of temporality and how we classify or think about the distinctions between modern, contemporary and the post-contemporary. Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik posit that the post-contemporary is the result of time being speculatively reorganised because of the complex systems, infrastructures and networks that structure society. For example, an algorithm procedure recommends a book that we want based on its study of our pattern of consumption—the predictive technology produces the present reality of the purchase of the book. Thus, the post-contemporary condition is when the future prediction or speculation defines the present rather than a present decision defining what follows.2

Thus, the political crux of futurism is its orientation of time and its imagination of human agency in relation to time and technology. Counter-imaginations of futurism that position themselves as alternative, or as responses to the Western and/or developed world, have grown out of critical art discourse. These futurisms, like Gulf Futurism, Afro-Futurism or Sino-futurism, distinctly marshal regional, ethnic and colonial histories to reconstitute distinct imaginations of the future. These imaginations are distinct counter-mappings to a future plotted out by developmentalism models and Western knowledge systems that often elide local and indigenous histories and subjects.

In considering the wide horizon from which “futurism” is thought about, it is easy to think about “Southeast Asian futurism” as a similar counter-mapping strategy. Yet a historical investigation of “Southeast Asian Futurism” that moves away from the regional or futurism as tropes reveals a more sophisticated intellectual terrain. “Southeast Asian Futurism” is less an aesthetic movement than an intellectual movement that grew out of the field of futurology or future studies—a social science based on forecasting human developments that originated in a Cold War milieu with the development of cybernetics and computation.

The term “futurology”—a field of inquiry into the future of earth and mankind—was coined by Ossip Flechtheim in 19423 and developed while he was in exile. His writings question whether the use of technology in totalitarian political systems, particularly with reference to Nazi Germany, would produce a future that was evil or one of hope and liberation. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the development of a number of world institutes and organisations, and the flourishing of futurology as a more inclusive discourse beyond the agendas set by governments, military establishments or larger corporations. Bringing together different futurist groups around the world, the World Futures Studies Federation was founded in Paris in 1973. Its founding was quickly followed by the Fourth World Futures Conference in Frascati, Rome in 1973. It intended to educate a new generation of “futurists” and to lay out a field of inquiry directed at systematically studying human development and forecasting. The Indonesian polymath and intellectual Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana (STA) was one of the Asian participants in the conference where he presented the paper, “The Place of Art in the Psychological, Social and Cultural Reconstruction of the Future. Calling for “a new avant-garde,” he positioned the artist as playing a critical part in building a post-Cold War future. He believed that the aesthetic experience was foundational to societies and culture was a representation of a value system, and that artmaking and appreciation created a a feedback loop between the individual and society.

After Rome, STA and fellow Indonesian attendees of the conference set to work planning their own conference. Developed with the World Federation of Future Studies in Rome, the 1987 International Conference on Art and the Future was the first futurology or futurist project to focus on the role of the artist. The conference took place in Jakarta from 8 to 9 July, in Yogyakarta from 10 to 11 July and in Bali from 13 to 15 July. Attendees included an international and regional network of forward thinkers: the Norwegian futurist Johan Galtung; French architect Yona Friedman; Japanese computer artist Shiro Takahashi; Malaysian architect Lim Chong Keat; Indian futurist Padma Seth; Thai intellectual, writer and founder of the Sathirakoses-Nagapradipa Foundation (1969), Sulak Sivaraksa; Indonesian writer, Mochtar Lubis; Filipino artist and writer Alfredo Roces; Indonesian artists Popo Iskandar and Moerdowo, among others.

By the end of the conference, the attendees advocated for a permanent institution to “continuously organise activities that would bring together artists, scientists, and futurists of all kinds—researchers, philosophers, humanists, politicians and the public at large to explore together the role and meaning of art in the emerging world society and culture.”4 The Futurist Experimental Art Center, Balai Seni Toyabungkah, took on this role. STA had established the center after returning from Rome in 1973. A place of study and reflection, Bali Seni Toyabungkah contained a library of over a thousand books on art, published the Art and the Future Bulletin, and served as a place for artistic collaboration where traditional and modern artists from different disciplines could meet met and developed artistic practices across different mediums.

At the 1985 Southeast Asian Writers Meeting at Balai Seni Toyabungkah, STA extended his ideas on the role of the artist to “Bumantara,” a term he coined by combining bumi (land) and antara (in between) to reference Southeast Asia. He believed that the cultural history of Southeast Asia, which informed the artistic production of Balai Seni Toyabungkah, was one of amalgamation. He considered this a vital quality for building a new international order that could overcome the inherent destructive tendencies of an international order built on competitive nation-states, as well as address the issues at the heart of the climate crisis. STA believed that encounters with Southeast Asian art and art practices could cultivate values in individuals and societies that could in turn “rewrite” the future of the world.

The National Gallery Singapore has the largest public collection of Southeast Asian modern art. STA was one of a number of regional intellectuals and artists who thought art played a critical role in defining the nation, the region and the world. Taking inspiration from STA’s conception of Bumantara, this article features a number of artworks from the Gallery’s collection and the National Collection that capture the cultural and regional zeitgeist from which STA’s ideas emerged, uncovering other important artists and futurists.

The painting was a gift from the Indonesian painter Basoeki Abdullah to Singapore in 1959, and was received by then Minister of Culture S. Rajaratnam. The artist had produced this work towards the end of his stay in Singapore sometime in the late 1950s, when he was using Singapore as a regional base. During this time, he also participated in Singapore’s 1959 Constitution Exposition. The largest trade exposition of Southeast Asia to date at the time, it was organised by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce to celebrate Singapore’s independence.

When the artist returned to Singapore in 1989 to seek out this painting for publication in his monograph, he claimed that the painting represented the future of Singapore. In fact, the structures in the painting reference key historic sites, such as the temples for Ramesses II and Queen Nefertari at Abu Simbel, which had to be relocated in 1964 as part of Nassar’s ambitious Aswan Dam project (1970). This relocation project, as well as the mechanical treatment of Borobudur, speak to how Basoeki Abdulla was inspired by the visions of a shared future and the possibilities for allied progress between “coloured nations” that were shared at the seminal Bandung Conference of 1955. The Bandung Conference, also known as the Afro-Asian Conference, was attended by 29 countries from across Asia and Africa, many of which were newly independent, that came together to discuss the possibilities for Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation.

The artwork is currently on show in the Gallery’s latest special exhibition Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, which runs from 18 November 2023 to 24 March 2024.

This artwork was Khoo’s first large-scale painting. Commissioned by the Malaysian architect Lim Chong Keat for the opening of the Singapore Conference Hall (SCH), the artist completed the artwork at Lim’s home in Pasir Panjang. The painting was displayed prominently in SCH, which was built as the headquarters of the National Trades Union Congress. The building, which also hosted various exhibitions and conferences, was gazetted as a national monument in 2010.

Khoo was part of a network of abstract artists from across Singapore, Malaysia and the world that was associated with Lim Chong Keat. In this artwork, Khoo’s evocative surrealist style is used to depict humans living in a mythical landscape dominated by natural elements like the sun and trees. Considering that Singapore only achieved sovereignty from the United Kingdom in 1959—just six years before this painting was made—the artwork brings to mind the nativist imagination of national iconography used to communicate the “authentic uniqueness” of postcolonial states that was primordial and therefore not colonial. At the same time, this definitively abstract painting can also be read as a statement announcing the modern progressiveness of Singapore on a world stage.

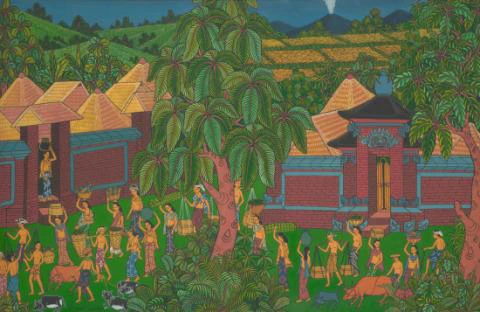

Runia Mungku was a member of the Young Artists of Penestanan (also termed the Peasant Painters of Penestanan by Malaysian architect Lim Chong Keat), a collective that emerged in Bali in the early 1960s. Associated with the tutelage of Arie Smit, it consisted of young men and self-taught painters living in an agrarian society. Known for their bright, brazen colours and thick graphic contours, the works of The Young Artists are recognised as belonging to the naïve style. Unlike traditional Balinese painters who represented Balinese myths, The Young Artists chose their themes from their natural and human surroundings. Their appeal in the 1970s and into the 1980s was that they painted their lives, and were essentially a community of self-taught painters that betrayed a unique modern sensibility in their paintings.

Through Lim’s influence and network, The Young Artists participated in the 1976 Campuan Meetings organised by artchitect futurist Buckminister Fuller. This painting was most likely purchased from one of the two exhibitions of paintings by the collective in 1971 and 1979, organised by Lim and held at the Art Gallery of the National Museum Singapore.

David Medalla. Sand Machine ‒ Blue Bamboo Batangas. 1963‒2019. Wood, copper, sand, glass, seashells and bamboo, 85.5 x 69.8 c 69.8 cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Davide Medalla’s Sand Machines are an amalgamation of futurist thinking and personal memory. Medalla noted that the initial inspiration for his first sand machine came from his memories of the rice terraces of the mountain provinces of the Philippines. Subsequent Sand Machines were based on memories of the beaches in the Philippine Islands, like the island of Cebu where Medalla’s mother came from. This include such as the ones that Medalla made for the 1999 exhibition Force Fields, curated by Guy Bret, that was on show at MACBA in Barcelona and the Hayward Gallery in London. At the same time, Medalla has described Sand Machine as a work that looked into “the possibility of deserts being reclaimed with energy that's available from the sun, to produce food.” The artwork thus registers an emerging ecological consciousness among artists who were becoming increasingly aware of the impending climate crisis. In 1972, the Club of Rome, a non-profit organisation of intellectuals and businesses leaders, published “Limits to Growth,” a report that used a computer simulation to demonstrate that the Earth could not sustain industrial development indefinitely.

Medalla is a prominent figure in the history of art and technology. His machines were featured in Douglas Davis' seminal title Art and the Future (1975). The book, which documents the radical turn in 20th century art away from the artist’s studio towards a collaboration with science and technology, positions Medalla amongst the Western technological vanguard. The use of organic material in his machines and installations sets him apart from his Western peers, while the confluence of memory and forward- thinking in his futurist artworks illustrate their distinctly Southeast Asian perspective.

The artwork is currently on show in the Gallery’s latest special exhibition Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, which runs from 18 November 2023 to 24 March 2024.

In 2011, Heman Chong presented a series titled Calendars (2020‒2096), a collection of 1,001 images of empty void decks, IKEA showrooms, airport terminals, shopping centres—public spaces in Singapore devoid of people. Presented as a calendar, each image represented a month, starting in January 2020 and running till 2096. To make the work, Chong documented liminal spaces over a period of six years from 2004 to 2010— spaces he described as “susceptible to change, to every sway of policy, to every new wave of capital”—and used these documents to map a future. In developing the work, Chong was interested in the future horizon-making of political projects. In this sense, Calendars also reflects a wider societal technocratic interest in futurology’s ability to develop value propositions of the future while being based on the present.

From 2019 to 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic emptied out public spaces as individual and communities took shelter indoors. Calendars (2020‒2096) seems to have unwittingly predicted a future that no one could have known in 2011. By unintentionally ”predicting” the future, the work has set itself up for the task of mapping a future from images of the present and past.

Notes

- Anne Bowler, “Politics as Art: Italian Futurism and Fascism,” Theory and Society 20, no. 6 (1991): 763–94. .

- Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik, eds., The Time Complex Post-Contemporary (Miami: [NAME] Publications, 2016).

- “Re: When the term futurology was coined?” Research Gate, 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/post/When-the-term-futurology-was-coined/5576af9f5cd9e349338b457a/citation/download.

- “Temporary Statue,” 151.