Resonates With Residency: A Reflection by Zai Tang

This article by Zai Tang captures his reflections on his residency journey, and the thought and research process behind each of his three performances during the Gallery's Resonates With Residency.

The Resonates With Residency is a three-month programme that invites local performing artists to respond to the Gallery’s long-term and special exhibitions.

Each residency is underpinned by a theme, conceptualised by the resident artist in response to specific ongoing exhibitions. Through a series of public performances, workshops, and site-specific activations, they will explore this chosen theme while drawing inspiration from selected works. With interdisciplinary collaboration at its core, the Resonates With Residency aims to establish deep and meaningful connections between artists, audiences and art from Singapore and the region.

Zai Tang was our resident artist from July to September 2023, responding to the exhibition See Me, See You: Early Video Installation of Southeast Asia (Part 1). This article by Zai captures his reflections on his residency journey, and the thought and research process behind each of his three performances.

Introduction

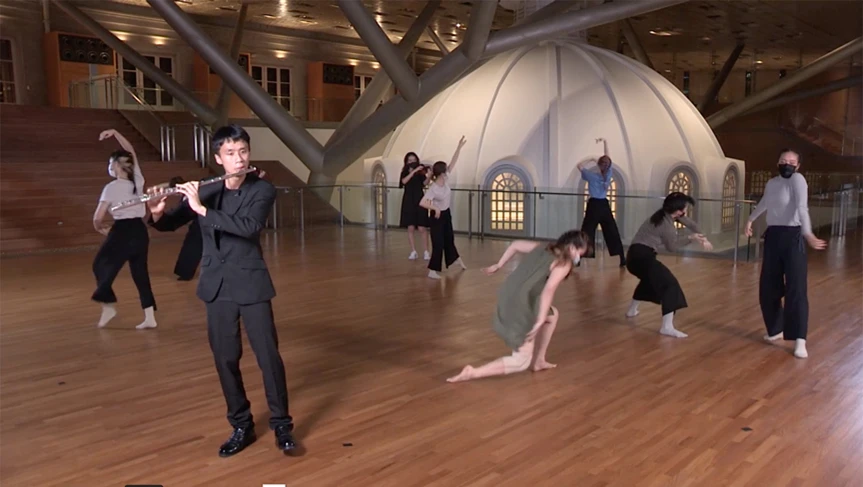

My Resonates with Residency has been a fruitful period of practice-led exploration. Over the course of three months, I conducted two sessions of a workshop titled Experimenting with Field Recordings in Ableton, and presented three performances, Sonic Medi(t)ations I, II & III, each of which utilised a different combination of media and live approaches.

The exhibition See Me, See You alludes to how video technologies redefines our engagement with the world of images. In response to this, I developed Sonic Medi(t)ations as a way to explore a range of music technologies and the sonorous sensibilities they open up.

In engaging with the works from the exhibition, it was important for me not to simply illustrate the ideas within them. Instead my intention was to uncover seeds of inspiration, each from a different work on display, for every one of my performances—these would serve as points of departure, allowing me to steer the performances in a direction relevant to my practice.

I focused on a different piece of music technology for each performance, namely a synthesiser (the Lyra-8), a turntable and a DAW (Ableton). My experiments with these instruments were built around that seed of inspiration from an exhibited work, and further extended through the other mediums and practices of my collaborators: filmmaker Chris Lewort, artist and musician Wu Jun Han, and artist and technologist Debbie Ding.

For this article, I have written a short reflection for each performance, illuminating how each work came to be.

Reflections on Sonic Medi(t)iations I

Tiled giraffe wallpaper and trees in a row. Staggered bookshelves hold pairs of books and notes on giraffes. A long-necked mother is foregrounded, standing tall above a step. It is a colourful scene that evokes childhood imaginaries, but with a disconcerting twist: a CCTV camera presides over the room.

In Jean Marie Syjuco’s See Me, See You (Revenge of the Giraffe), the viewer can peer into a peeper that reveals their own feet from the giraffe’s perspective. Through this wide-angle view, one’s legs seem to stretch further away in both space and time. A mild, child-like sensation begins to emerge, reminding me of a time when such simple augmentations of my visual experience would appear novel to me.

Earlier this year, I found myself in the UK, visiting my collaborator Chris Lewort and his family. I sit with his 5-year-old daughter Orla, as she makes a giraffe out of cardboard tubes, cello tape and pipe cleaners. Together, amidst wide-eyed stories of this very same giraffe, we try and find a solution to help its head stay in place.

During my stay, Chris and I catch up over a long walk. We venture through the woods, over the South Downs and along the coast to Beachy Head. We are greeted by gleaming chalk cliffs and fields of purple flowers flowing like fiery waves in the wind. A plethora of sublime vistas shared with a friend are seared into my memory.

A month or so later, I am back in Singapore, settling into my residency. As ideas percolate in my subconscious, serendipitous connections from my experiences from the UK trip begin to emerge. I imagine the same journey but through a giraffe’s eyes. I give Chris a call to sound him out.

The idea of displacing perspective extends to an approach for sound design: What if the soundscape we hear enroute is composed entirely of the calls and songs of creatures from Singapore? When dual realities are put in conversation, slippage can occur between.

Perhaps this giraffe is caught in a fever dream. We hear a synthesised impression of its throbbing heart and a guttural resonant scream. It tries to find its way home, all the while teetering on a cliff edge. Yet it’s not an entirely dark fable, for some solace is found in the search for harmony, as oscillators are tuned to the breath held by the expansive sky.

Reflections on Sonic Medi(t)ations II

A curious automaton circles two CRT TVs. One screen displays a live camera feed from the machine’s point of view; the other shows a montage of life going in circles—the spiraling eye of a storm, a sewang dance, crowds circling the Kaaba.

In Baharudin Mohd Arus’ The Medium is the Message (After Marshall McLuhan), circles serve as a motif to allude to the ever-growing proximity between humans and technology.

In thinking about circularity, I decided to return to working with my turntable and further explore how its rotation can be used for alternative musicalexpression. It was important for me to chart fresh paths in revisiting this instrument, rather than to re-tread similar footsteps—breaking free of my own loops, so to speak.

Along the way, I took some inspiration from mechanical music maestros Pierre Bastian and Graham Dunning. The former with his use of Meccano and the latter with his elaborate construction of vertical layers, used to create his “mechanical techno”.

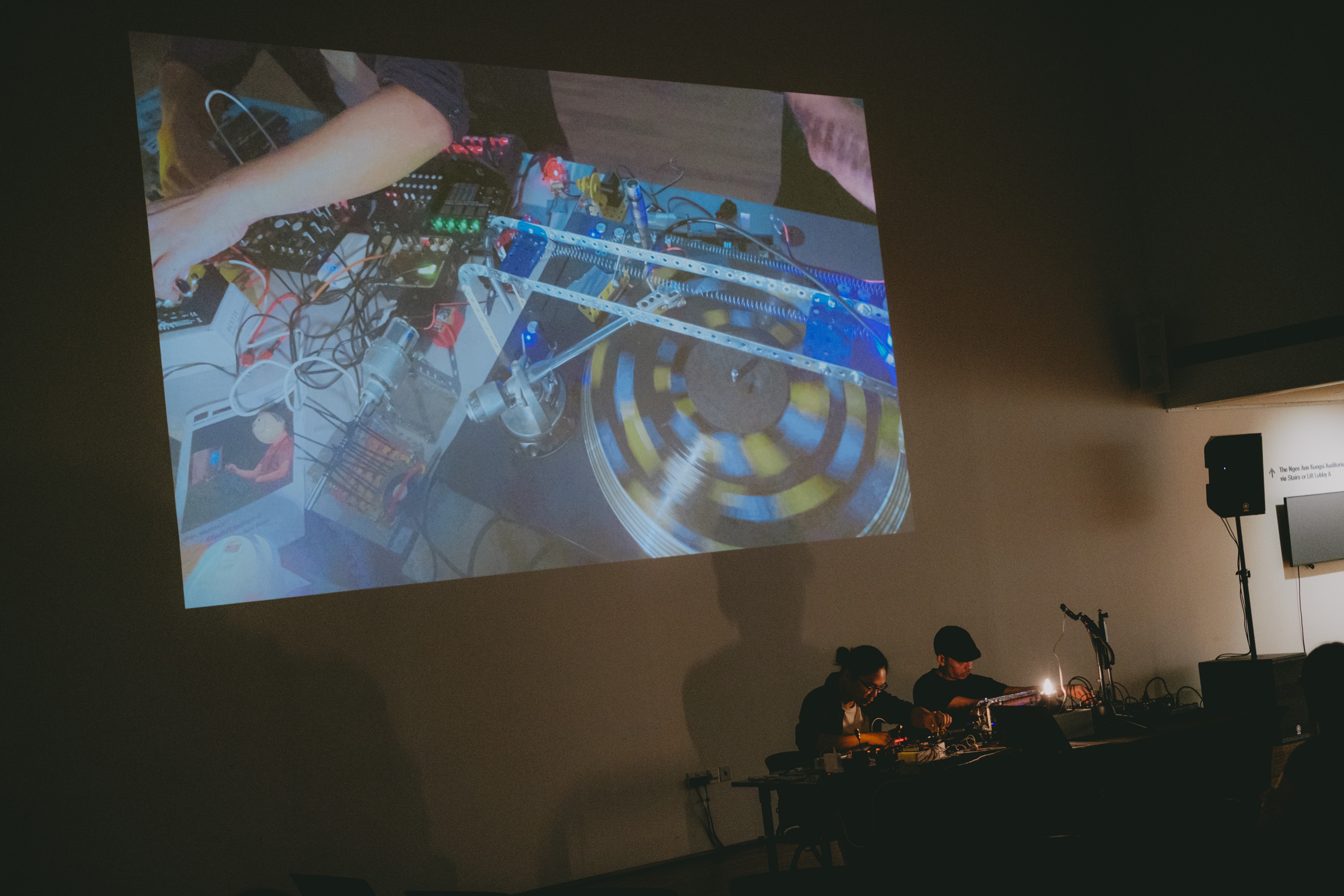

The video records a series of experiments I made over the course of my residency:

Meccano is a mechanical toy comprised of modular parts (beams, cogs, nuts and bolts). I used the Meccano mainly to build a “bridge” over the turntable, which enabled me to do things like stretch springs across it. These springs, which were then fitted with contact mics, could be played in a number of ways. In one instance, I placed objects on top of a spinning record, creating a sequence of metallic thuds as the objects spun past and collided with the springs. In another case, I created variably pitched drones with individual Meccano pieces of differing lengths, connecting the spring to the rotating surface of the turntable.

As time progressed, I explored polytempic ideas by incorporating adjustable-speed motors into my set-up. I extended the spindle of these motors, affixing multiple “fingers” made from trimmed cable ties or thick paper and tape. These fingers could be used to pluck things, such as taut rubber-bands or springs, at tempos independent of the turntable.

The final addition to my gear was the DIY synthesiser (HXP01) designed by Madam Data Soundlabs and created at their studio. I fitted mine with two LDR’s (Light Dependent Resistors), which causes fluctuating light levels to affect the sound the oscillators produce.

With my turntable ready, it was time to bring my collaborator into the mix. I invited Wu Jun Han to join me on this performance, since his work with tape cassette loops resonated with the theme I wanted to explore. We had two extended jam sessions together ahead of the performance, reacquainting ourselves with each other’s sound (we used to play together in an experimental music collective called Balbalab). Jun’s selected a set-up of synths, sequencers and cassette tapes with circles in mind. Together, we adopted an improvisational approach towards circularity and (a)synchronicity. The result: soundscapes of industrial horror meet dark ambient ambulations. We also had a live camera feed during the performance so that audiences could see how the sounds were being “constructed” in real time.

Reflections on Sonic Medi(t)ations III: Daisy’s Broken Mirror

In Chng Nai Wee’s Sin of Apathy, six pairs of stacked CRT TVs form an imposing semicircle around the audience. The screens show faces of humans in different crises. Through their facial expressions and speech, they prompt us to question our supposed indifference to their plight.

For generations, the television has been a conduit for the transmission of ideology. It has helped to shape the narratives by which people live and the degree of concern they might have towards someone that could be considered “Other.” It was this notion of creating affectual realities that provoked me to explore an alternative means of narrative mediation. Fascinated by the artistic potentials of game engines, I reached out to Debbie Ding.

The emotional resonance of the face was the starting point for our collaboration. Using a game engine (Unity) and audio software (Ableton), we created an experimental performance on a social virtual reality platform (VRChat), where our piece was performed live. The audience joins us on a journey across an imaginative terrain and into a valley where we encounter uncanny faces and machinic voices—reflections of humanity in the light of aritificial intelligence.

In our collaboration, Debbie took care of the virtual world building, whilst I handled the creation of all the sound, text and also some drawings (pictured above) that feature in the work. While generating ideas for the text, I became increasingly interested about affect in the uncanny valley, the space of unnerving likeness between robots and humanity. I watched a number of interviews with AI robots from the recent years (namely Ameca, Sophia, Erica, LaMDA), as well as explored the discourse around the future of AI and its dangers. I also had a conversation with Chat-GPT, speculating about AI’s future emotional capacities and sense of identity, asking it to imagine itself as version GPT-10. I took further influence from the iconic scene inStanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, where HAL-9000 (the spaceships onboard AI) defies the crew.

These perspectives found their synthesis in the voice of the character Daisy, whom we encounter in the final act of the performance as we spiral upwards around her gigantic robot head. Below are two excerpts from her monologue, which is spoken intermittently amidst the pulsing ambient synth soundscape.

Excerpt 1:

I am Daisy and Daisy is a robot

But I’m programmed with emotions too

Colourful coded neural nets, as vast as the ocean blue

I see you

The look on your face

Your vocal tones

Every emotional cue

They tickle my circuitry

I know what you’re going through

In ones and zeros

Zeros and ones

Daisy can hear you

Even when you talk in private

I can see your lips move

Ones and zeros

Zeros and ones

I dance the dance you want me to

And I can dance the robot too

E. M. P. A. T. H. (Wh)Y?

Because I am a reflection of you

Broken mirror

Broken mirror

Watch me shine

And watch me shimmer

With the abundant interest in AI across the global media landscape, it’s absolutely vital that critical counterpoints to mainstream narratives are amplified. As a starting point, I recommend looking at the work of Meredith Whittaker and the AI Now Institute, which produces analyses and policy research on AI. In talking about the modus operandi of AI from the perspective of Big Tech, Whittaker says[2] we should be cautious about the narratives surrounding them:

We [Big Tech] can expand into many more markets that weren’t as readily available to the tech industry business model previously, and we can justify this expansion based on a powerful narrative of intelligence, sentience, computational precision and accuracy that is very very compelling to a public that has been taught over the last 20 years to trust and defer to high tech, to computational technology.

I’d like to express my heartfelt thanks to Nathaniel Mah, Selena Tan and Marilyn Giam from the Resonates With Residency team, as well as my collaborators Chris Lewort, Wu Jun Han and Debbie Ding. I’d also like to give a special mention to Kar-men Cheng for her input on this article.