To Care: A Reflection on Art and Conservation

Singaporean art practitioner Celeste Tan reflects on the care that sustains artworks, from making to conservation.

Share

For an artist, care is embedded in creation, rooted in deep attention and sensitivity to the interplay of existence and introspection. The artistic process—capturing life’s beauty or exploring philosophical depths—begins with care that manifests in choices often invisible to casual viewers: the selection of materials, themes, space, subject matter, the weight of a brushstroke, and how they are presented.

Early in my practice, materials were just tools that helped me express and translate. That changed when I met my mentor, Lim Kay Hong laoshi (林家雄老师). He taught me that art is not just a language or an expression but a lifestyle. Materials must be carefully chosen and handled with reverence. When the honing of art leads to a cultivation of self and sensitivity to one’s surroundings, I believe that this is the beauty of care and the joy that comes from making.

I have always wondered if we could cultivate the same attitude of care toward our materials and our making, not to exploit but to utilise and take this attitude further, toward our neighbours, and if we could not cultivate a better society.

I briefly encountered Tang Da Wu laoshi at Reminder: I Don’t Do Exhibitions, held at Art Outreach. A mother and her daughter were also visiting the gallery, and the mother asked Tang if he could share anything with her daughter. I felt great earnestness from Tang when he shared that “Every work is a self-portrait.” That humbled me, and my perspective on art has changed.

Encounters create ripples that can collide and lead to new currents, which in turn create new ripples. That encounter with Tang resonated deeply, reminding me of the value of care in making works and my artistic practice. It also reminded me of when I was once criticised for choosing a substandard canvas for my work.

A substandard canvas becomes brittle with time, betraying the very act of creation. That moment of realisation shifted my practice. Now, I take the time to understand my materials and respect the artisans behind my tools. I strive to be worthy of them.

The Conservator’s Care: Listening Through Touch and Dedication

Care does not end with creation; it extends into preservation. Conservation is often perceived as an act of repair, a process that begins when damage occurs. However, true care in conservation begins the moment a work is created.

Generally, a painting or a work is considered complete when the artist puts down their brush. However, in traditional Chinese aesthetics, this is merely the first step. An unmounted artwork is not yet a finished piece. As a saying goes, an artwork is “三分书画,七分裱 (three parts painting, seven parts mounting).”

The practice of shui mo hua (水墨画, also known as ink painting) reflects a deep care for its materials at every stage. Like its name, its practice is inextricably tied to its materials. The weight, texture and absorbency of the xuan paper (宣纸) selected when creating a work fundamentally shape a painting’s outcome. Both skilled painters and experienced conservators can assess the quality and condition of paper through touch alone, discerning a painting’s age, authenticity and condition based on the material used and the texture of its mount.

Mounting holds a profound significance in the art practice of shui mo hua. It was only natural, then, that as a practitioner, I was drawn to the art of mounting and conservation.

I had the privilege of studying under Eve Zhang laoshi (张艳老师), who specialises in Chinese painting and calligraphy restoration. She taught me that mounting is more than a technical process—it expresses care, foresight and cultural continuity. Each layer of paper speaks of a legacy deeply rooted in heritage.

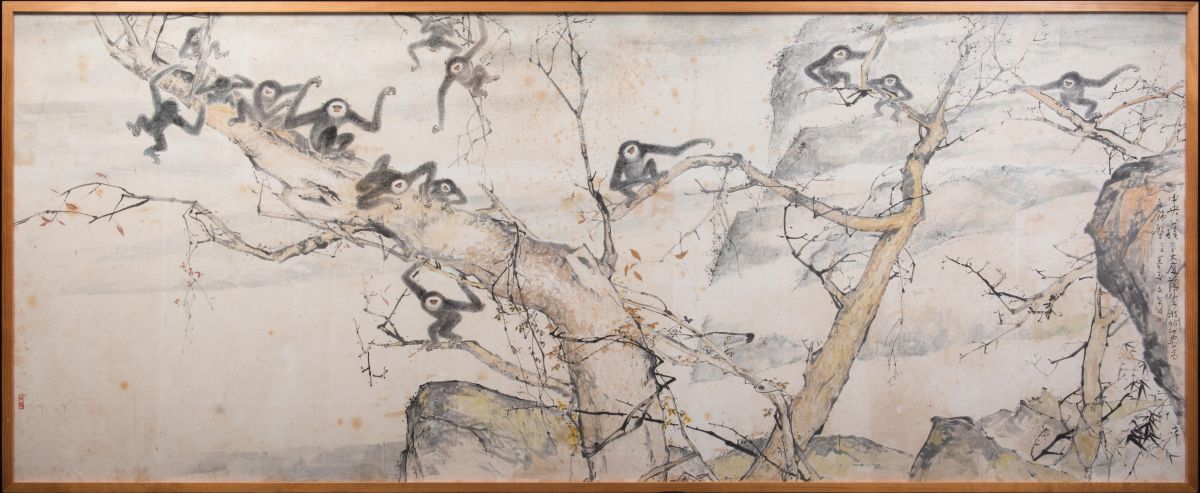

Eve and her father, Zhang Xiaozhai laoshi (张孝宅老师), are also the conservators who worked alongside the Heritage Conservation Centre (HCC) on the monumental restoration of Chen Wen Hsi’s Gibbons—a 1977 masterpiece whose conservation process spanned over a year. I was fortunate to have been allowed to observe parts of this process. It was a rare opportunity to see how, with patience and reverence, a work could be brought back to life.

That experience further deepened my understanding: when handled with respect and knowledge, artworks—and their materials—can be preserved for generations to come. The Zhangs’ approach mirrors the time-honoured methods of traditional Chinese mounting, where the goal is to support the artwork and prepare it for future renewal. Watching their work, I understood. Care is knowledge, accumulated through years of dedicated practice.

In Eve’s studio, I learned that even seemingly small decisions—how a scroll is backed, how a frame is sealed—have enormous implications for a work’s longevity.

Hand mounting is a slow, meticulous process that allows the painting to breathe and adjust to its environment at every stage. Each step is given time to rest. This phase is critical. The materials used in hand mounting—such as natural starch paste and xuan paper—are lightweight, breathable and sympathetic to the artwork. They expand and contract with the painting, instead of resisting it.

Most importantly, hand mounting is a reversible process. A hand-mounted work can be safely taken apart, cleaned and remounted. This cyclical renewal is what allows paintings to survive across centuries. In contrast, machine mounting is faster—often cheaper—but compromises the work’s future. Layers are fused with synthetic glues, heat and industrial pressure, sealing the artwork permanently. Once damaged, it cannot be safely restored.

I learned this lesson the hard way. I once brought a mounted work to Eve for review. She touched the edges and immediately knew. “This is machine-mounted.”

I protested. I told her I had paid for hand mounting.

But she shook her head. “It’s too thick, too rigid.”

I resisted, unwilling to believe that I had been deceived. We decided to test it. As we began the delicate process of removing the mounting, my heart sank. Beneath the layers, my painting—a spontaneous first attempt at a single-stroke duck—was fused to a synthetic, rubbery glue. It was irreversible. In that moment, I grieved—not just for the loss of the artwork, but for the trust I had misplaced and my lack of knowledge.

A Culture of Care: Beyond the Individual

True care in art requires collective effort. It lies in the hands of the artist, the collector, the curator, the conservator. It is an ecosystem where every decision, from the choice of materials to the method of mounting and the housing of the works, affects the life of an artwork.

I hope that more people will understand the invisible care embedded in every work of art. The care of the artist who selects their materials with intention. The care of the conservator who listens with their hands. The care of those who house and display art, ensuring that it can be appreciated for generations to come.

Because in the end, to care for art is to care for time itself—to honour both the moment of creation and the endless future it deserves.