Notes on Photography: Tan Lip Seng's Industrial Century

Now in UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 7, Industrial Century is one of artist Tan Lip Seng’s earliest photographs. Charmaine Toh shares more about this work featuring the Iron and Steel Mill in Jurong, a favourite subject of photographers in Singapore.

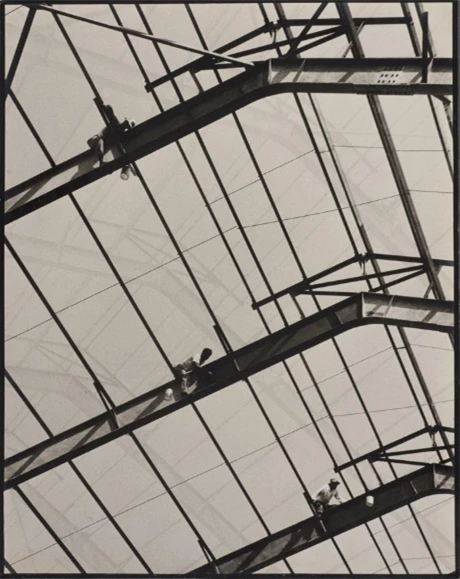

Industrial Century, 1963

Gelatin silver print

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Singaporean photographer Tan Lip Seng is best known for the semi-abstract colour slides he made in the late 1960s and 70s, but like many of his peers, he started out taking photographs on black and white film.

Industrial Century is one of his earlier prints, featuring a scene of three labourers perched high atop the roof struts of a building in construction. This building was the Iron and Steel Mill in Jurong, a favourite subject of photographers. Made in 1963, the print shows the hand of a confident photographer unafraid of high contrasts and sharp edges. The repetition of lines of the roof and the three labourers could symbolise the mechanised nature of industrial urban life, which is also hinted at in the work’s title. However, Tan takes the composition a step further by doing a second exposure of the same shot, reversed horizontally, and with a shorter exposure time to create the faint tones that seem to lie in the background. The doubling of the image brings an added depth to the photograph and points towards Tan’s later experiments with the layering of coloured transparencies. Industrial Century was one of 12 black and white gelatin silver prints that Tan submitted for his application to become an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society (ARPS) in 1964. Following the rotation of works in our long-term exhibition galleries, the print is now on display at UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 7.

A medical photographer by profession, Tan was an active member of the Photographic Society of Singapore (PSS). He started practising photography in 1957, when he was only 15, learning through books before joining the PSS in 1959 as one of its youngest members. There he honed his practical skills through their weekly Sunday outings. Tan was a very successful salon exhibitor and went on to win numerous awards around the world. After gaining his ARPS, he applied for and became a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society (FRPS) in 1970 for his colour photography and was subsequently awarded Singapore’s Cultural Medallion in 1985. He was also recognised as a World’s Top Ten Colour Slide Exhibitor by the Photographic Society of America from 1969 until 1988. Between 1962 and 1997, Tan’s colour slides have been accepted more than 6,000 times and won more than 1,000 awards at international salons.

Tan counts senior photographer and fellow PSS member Lee Lim as one of his major influences, which can clearly be seen in his experiments with photo montage and layering. While Lee produced only black and white composite photographs, Tan extended those experiments towards colour photography. In the late 1960s, Tan developed a specific colour derivation technique using Ortho Film and dizochrome film. With this, he created the semi-abstract and brightly-coloured landscapes of Singapore that have become a trademark of his style. Each slide often comprised several layers of film, which were mounted together using a cardboard frame. They were never developed as prints during their time but circulated as 35mm slides and were viewed as projected images.

Made later in 1970, Under Construction (above) shows the development of Tan’s photographic practice. Like Industrial Century, it depicts labourers at work. However, it is a fragmented and abstracted landscape. The image has been manipulated to remove all unnecessary detail. The background is solid black, bringing our focus purely to the figures of the workers and the lines of the scaffolding. Unlike his medical photographs, whose objective was to make accurate and detailed records of patients, Tan’s artistic works went in the opposite direction. It was never his intention to make historical records of Singapore, but rather to express certain ideas or concepts. Nevertheless, through his many photographs of labourers, construction workers and samsui women, one may observe the way he was grappling with Singapore’s rapid industrialisation and imagining a new Singapore landscape in the new “industrial century”.